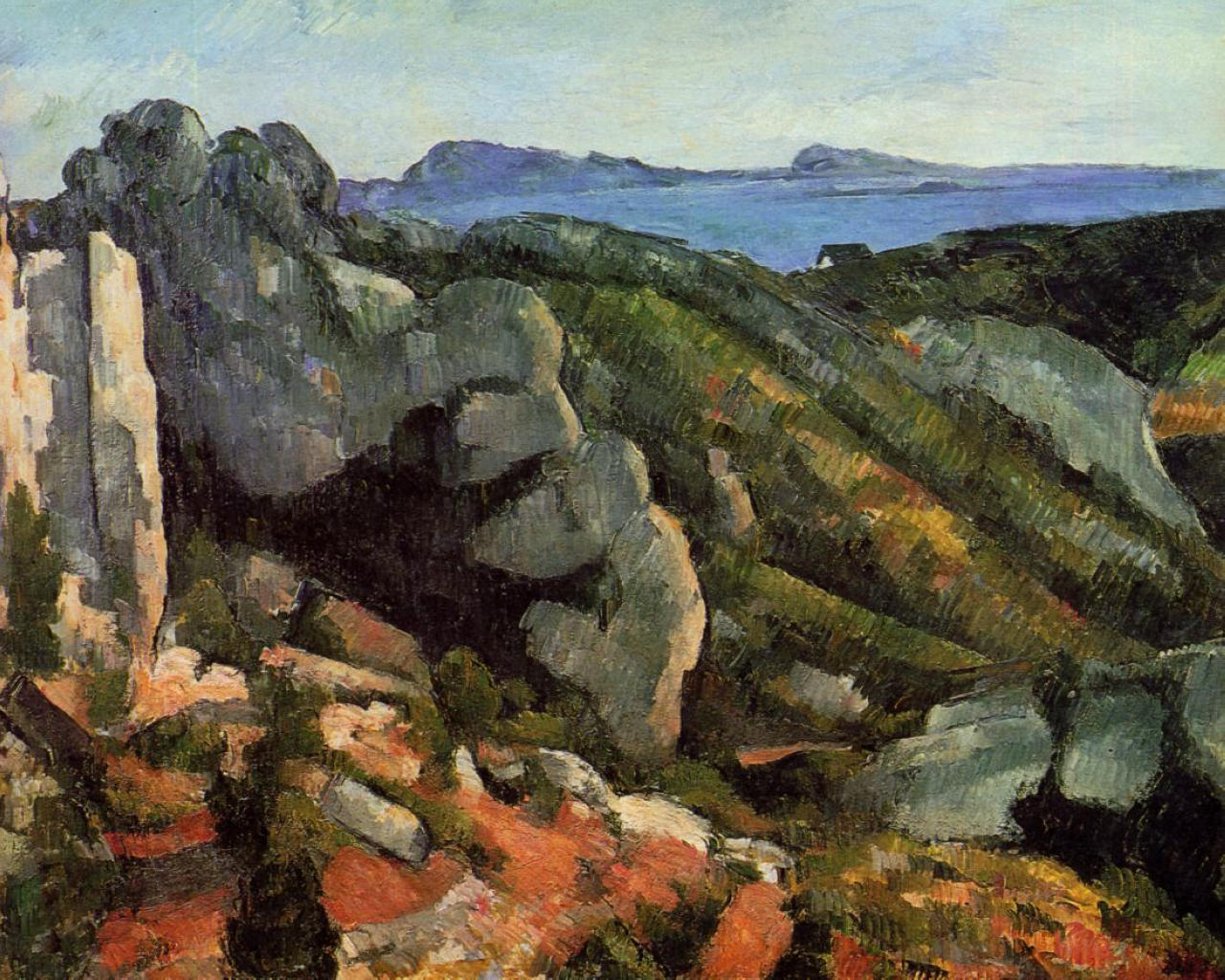

It is this limitless objectivity, refusing any kind of meddling in an alien unity, that strikes people as so offensive and comical in Cézanne’s portraits.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

October 18, 1907 (Part 2)

<…> This labor which no longer knew any preferences or biases or fastidious predilections, whose minutest component had been tested on the scales of an infinitely responsive conscience, and which so incorruptibly reduced a reality to its color content that it resumed a new existence in a beyond of color, without any previous memories.

It is this limitless objectivity, refusing any kind of meddling in an alien unity, that strikes people as so offensive and comical in Cézanne’s portraits.

They accept, without realizing it, that he represented apples, onions, and oranges purely by means of color (which they still regard as a subordinate means of painterly practice), but as soon as he turns to landscape they start missing the interpretation, the judgment, the superiority, and when it comes to portraits, there is that rumor concerning the artist’s intellectual conception, which has been passed on even to the most bourgeois, so successfully that you can already see the signs of it in Sunday photographs of couples and families.

And here Cézanne naturally strikes them as utterly inadequate and not worthy of discussion.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

SEEING PRACTICE: Cézanne’s portraits

I think Rilke is absolutely right: Cézanne’s limitless objectivity becomes almost unbearable to us, threatening even, in PORTRAITS.

What stares us in the face is the fleeting, illusory nature of our feelings and concerns and, ultimately, of our selves and our subjective identities. It is not exactly flattering to the ego to see itself reducible to color content…

The idea of “artist’s intellectual conception” is as good a defense against this realization as any.