Zola had understood nothing; it was Balzac who had foreseen or forefelt that in painting you can suddenly come upon something so huge that no one can deal with it.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

OCTOBER 9, 1907 (Part 3)

He became well known in Paris, and gradually his fame grew.

But he had nothing but mistrust for any progress that wasn’t of his own making (that others had made, let alone how); he remembered only too well how thoroughly Zola (a fellow Provençal, like himself, and a close acquaintance since early childhood) had misinterpreted his fate and his aspirations in L’Oeuvre.

From then on, any kind of scribbling was out: “Travailler sans le souci de personne et devenir fort—” he once shouted at a visitor.

But when the latter, in the middle of a meal, described the novella about the Chef d’Oeuvre inconnu (I told you about it once), where Balzac, with unbelievable foresight of future developments, invented a painter named Frenhofer who is destroyed by the discovery that there really are no contours but only oscillating transitions—destroyed, that is, by an impossible problem——,

the old man, hearing this, stands up, despite Madame Brémond, who surely did not appreciate this kind of irregularity, and, voiceless with agitation, points his finger, clearly, again and again, at himself, himself, himself, painful though that may have been.

Zola had understood nothing; it was Balzac who had foreseen or forefelt that in painting you can suddenly come upon something so huge that no one can deal with it.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

Rilke recounts an episode from Émile Bernard’s ‘Memories of Paul Cézanne’ (1907):

one evening, when I spoke to him of “Le Chef-d’œuvre inconnu” and Frenhofer, the hero of Balzac’s tragedy, he got up from the table, stood before me and, striking his chest with his index finger, confessed wordlessly by this repeated gesture that he was the very character in the novel. He was so moved that his eyes filled with tears. One of his predecessors, who had a prophetic soul, had understood him. (Translated by Alex Danchev, in The Letters of Paul Cézanne).

Even though Bernard doesn’t say so explicitly, Rilke seems to have inferred that Cézanne hadn’t read the novel. Nothing could be further from truth. Cézanne was a well-educated and well-read man. Alex Danchev writes in his introduction to “The Letters”:

His bedside reading was Balzac: a well-thumbed copy of the “Études philosophiques”, including “Le Chef-d’œuvre inconnu”, another source of self-projection.

SEEING PRACTICE: ONENESS AND SEPARATION

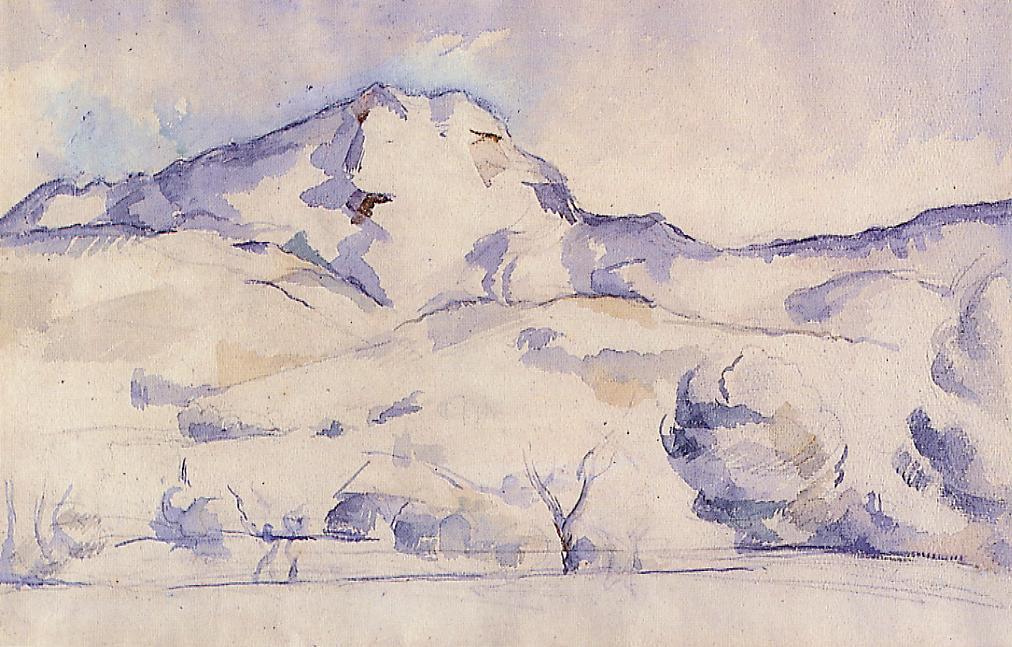

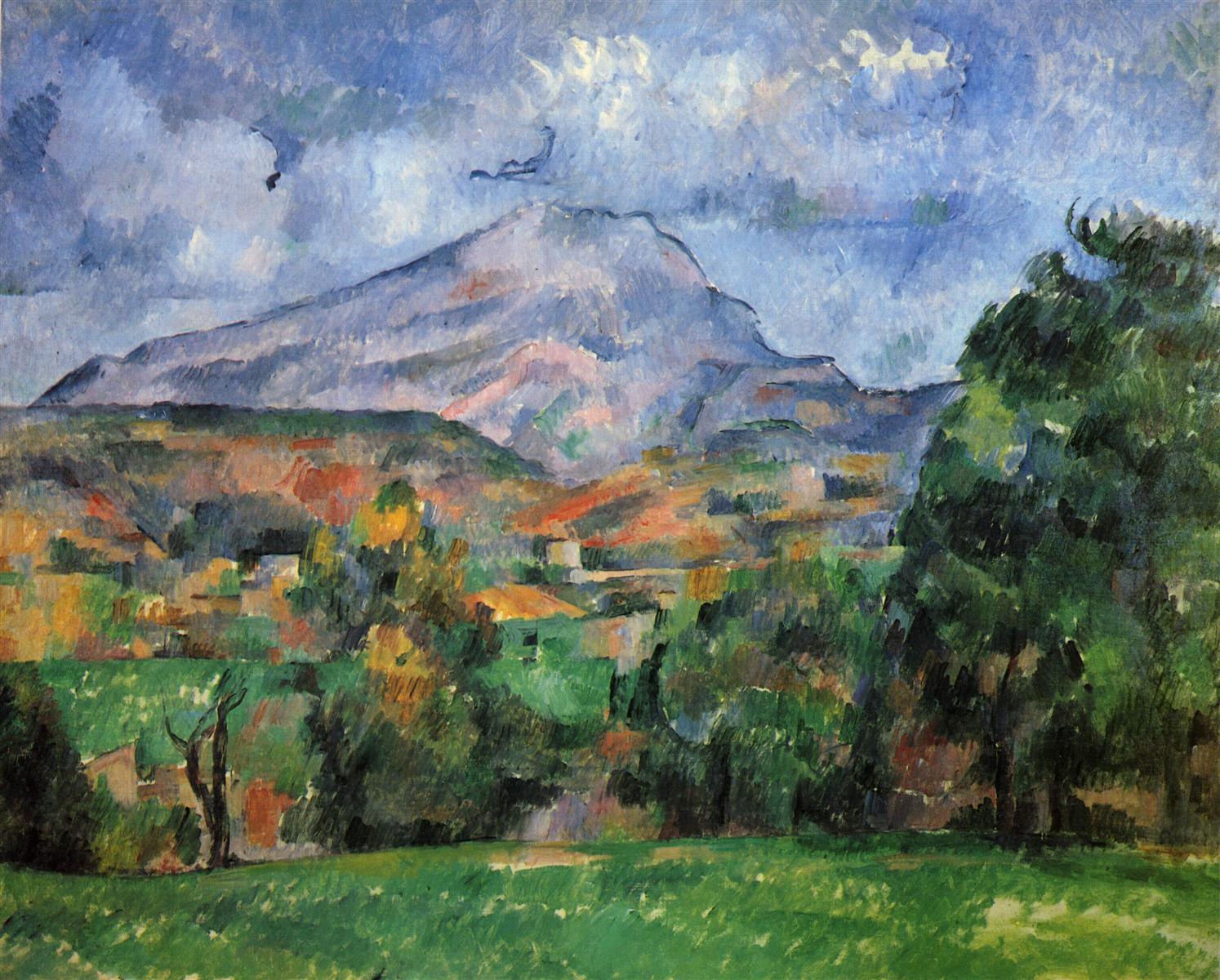

The painting I added to this letter is one of those where Cézanne went through the experience of contour-less sensations of color “all the way to the end”. No contours, only “oscillating transitions”, so that the reality itself seems to dissolve just as we are beginning to see it as it is.