… the inner equilibrium of Cézanne’s colors, which never stand out or obtrude, evokes this calm, almost velvetlike air which is surely not easily introduced into the hollow inhospitality of the Grand Palais.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

October 24, 1907 (Part 2)

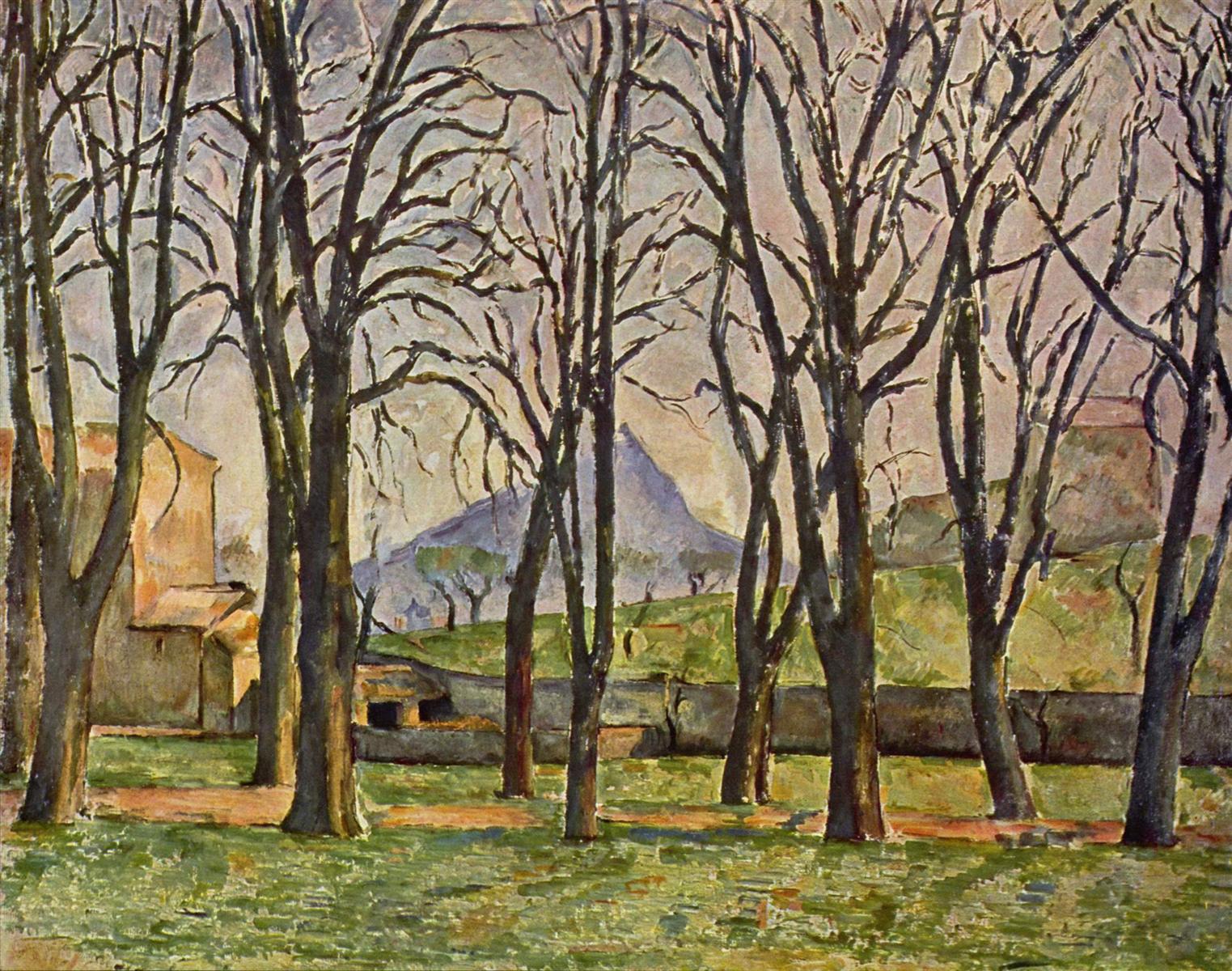

When I made this remark, that there is nothing actually gray in these pictures (in the landscapes, the presence of ocher and of unburnt and burnt earth colors is too palpable for gray to develop),

Miss Vollmoeller pointed out to me how, standing among them, one feels a soft and mild gray emanating from them as an atmosphere,

and we agreed that the inner equilibrium of Cézanne’s colors, which never stand out or obtrude, evokes this calm, almost velvetlike air which is surely not easily introduced into the hollow inhospitality of the Grand Palais.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

STORYLINE: INTERCOURSE OF COLORS

Many painters and art historians have attempted to define “color harmony”, and my guess is, these attempts will go on so long as men can breath and eyes can see.

This is in our nature, to try and “define” our words, our languages teasing us everyday with the organic fluidity of what we (with charmingly naive arrogance) call “meanings”.

(Rilke wrote once that happy is he who knows that beyond all languages sits the Unsayable.)

But I don’t expect that, in my lifetime, I will see a better description of what “color harmony” actually is than what Rilke gives in this letter.

SEEING PRACTICE: COLOR HARMONY

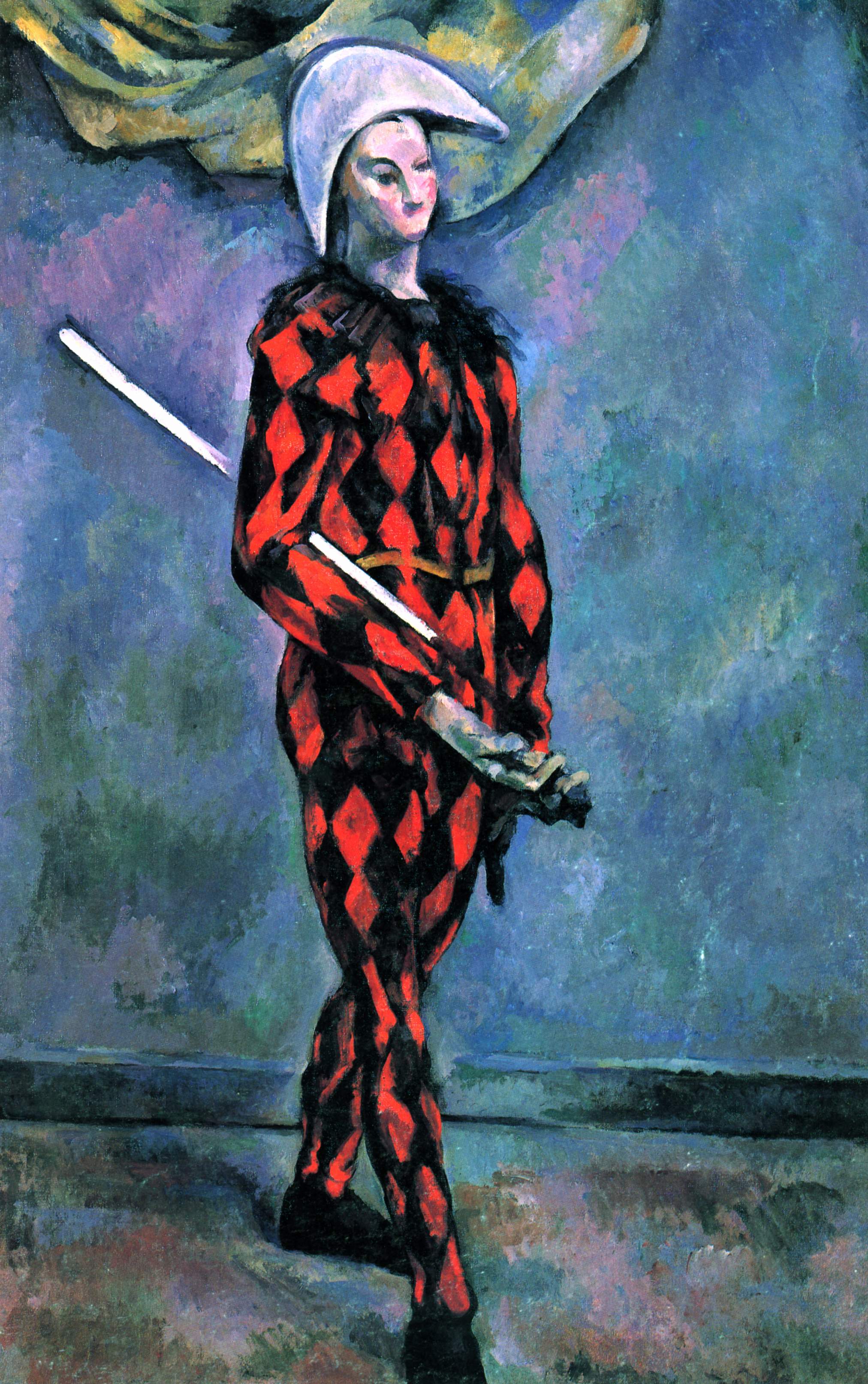

Cézanne mastered every register of this ancient organ of color. He could fill the seemingly grey with every color of the rainbow (and more), and bring the boldest, most intense colors into the state of quiet conversation with one another.

The paintings I have chosen for this segment range from the muted lightness of an evening forest to the bold pattern of Harlequin’s attire. Yet the effect described by Rilke is there in all and every one of them.