To achieve the conviction and substantiality of things, a reality intensified and potentiated to the point of indestructibility by his experience of the object, this seemed to him to be the purpose of his innermost work.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

In his description of Cézanne as a man, Rilke relied mostly on Émile Bernard, and his article “Souvenirs sur Cézanne” (1907); it doesn’t seem to have been the most reliable of sources (which Rilke intuited).

But Cézanne himself also contributed to a vaguely caricature legend of himself as (in Bernard’s words) “an event which most people no longer had the patience to experience”.

OCTOBER 9, 1907 (PART 1)

… today I wanted to tell you a little about Cézanne.

With regard to his work habits, he claimed to have lived as a Bohemian until his fortieth year. Only then, through his acquaintance with Pissarro, did he develop a taste for work. But then to such an extent that for the next thirty years he did nothing but work.

Actually without joy, it seems, in a constant rage, in conflict with every single one of his paintings, none of which seemed to achieve what he considered to be the most indispensable thing.

La réalisation, he called it, and he found it in the Venetians whom he had seen over and over again in the Louvre and to whom he had given his unreserved recognition.

To achieve the conviction and substantiality of things, a reality intensified and potentiated to the point of indestructibility by his experience of the object, this seemed to him to be the purpose of his innermost work.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

THE WORK

Cézanne writes to Bernard on July 15, 1904:

<…> The greatest, you know them better than I, the Venetians and the Spaniards.

In order to make progress in realization, there is only nature, and an eye educated by contact with it. It becomes concentric by dint of looking and working.

I mean that in an orange, an apple, a ball, a head, there is a culminating point, and this point is always the closest to our eye, the edges of objects recede towards a centre placed at eye level.

With only a little temperament one can be a lot of painter. One can do good things without being either a great harmonist or a great colourist. All you need is an artistic sensibility. And doubtless this sensibility horrifies the bourgeois. So institutes, pensions and honours are only for cretins, jokers and rascals.

Don’t be an art critic, paint. Therein lies salvation.

SEEING PRACTICE: Cézanne

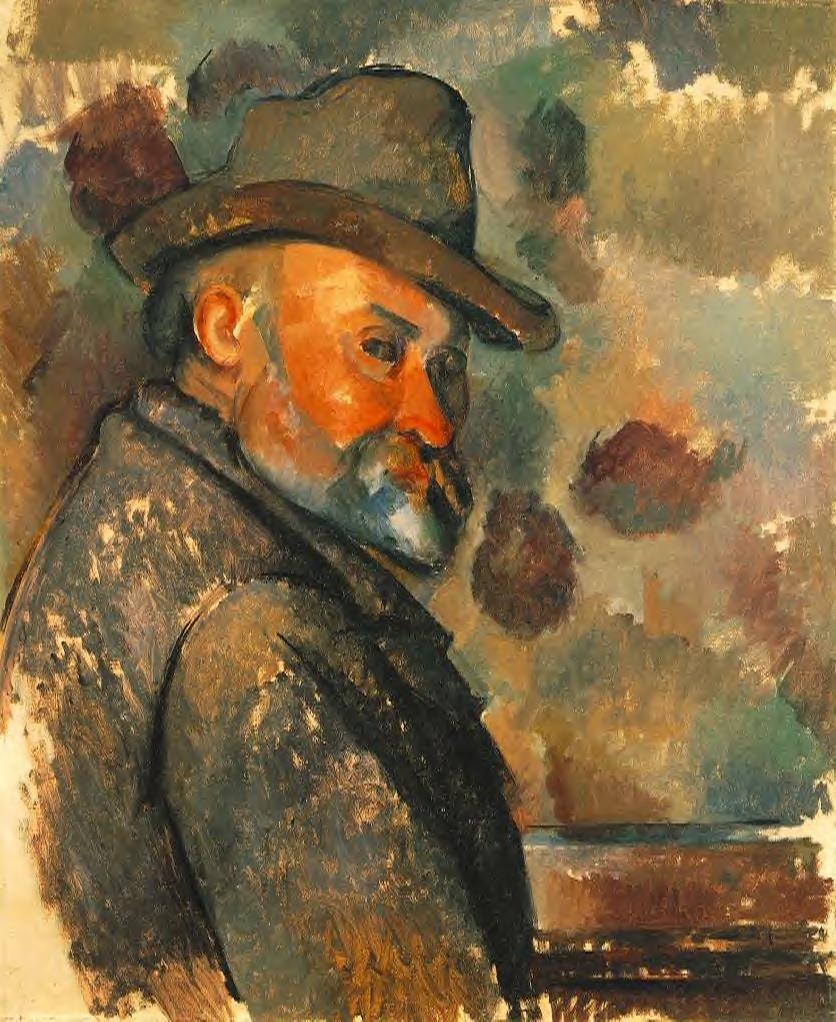

It is interesting to look at Cézanne’s own head, in this self-portrait above, with his own description of his way of seeing it:

I mean that in an orange, an apple, a ball, a head, there is a culminating point, and this point is always the closest to our eye, the edges of objects recede towards a centre placed at eye level.

Can you see what he means?