And all this lies out there with the generosity of a born landscape, and casts forth space.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

October 17, 1907 (Part 1)

<….> But the morning was bright.

A broad east wind invading us with a developed front, because he finds the city so spacious.

On the opposite side, westerly, blown, pushed out, cloud archipelagos, island groups, gray like the neck and chest feathers of aquatic birds in an ocean of cold, too remotely blissful barely-blue.

And underneath all this, low, there’s still the Place de la Concorde and the trees of the Champs-Éysées, shady, a black simplified to green, beneath the western clouds. Toward the right there are houses, bright, windblown, and sunny, and far off in the background in a blue dove-gray, houses again, drawn together in planes, a serried row of straight-edged quarrylike surfaces.

And suddenly, as one approaches the obelisk (around whose granite there is always a glimmering of blond old warmth and in whose hieroglyphic hollows, especially in the repeatedly recurring owl, an ancient Egyptian shadow-blue is preserved, dried up as if in the wells of a paint box), the wonderful Avenue comes flowing toward you in a scarcely perceptible downward slope, fast and rich and like a river which with the force of its own violence, ages ago, drilled a passageway through the sheer cliff of the Arc de Triomphe back there by the Étoile.

And all this lies out there with the generosity of a born landscape, and casts forth space.

And from the roofs, there and there, the flags keep rising into the high air, stretching, flapping as if to take flight: there and there.

That’s what my walk to the Rodin drawings was like today.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

STORYLINE: LANDSCAPE OF WORDS

As a painter, I know how to make landscapes out of paint. It is my craft.

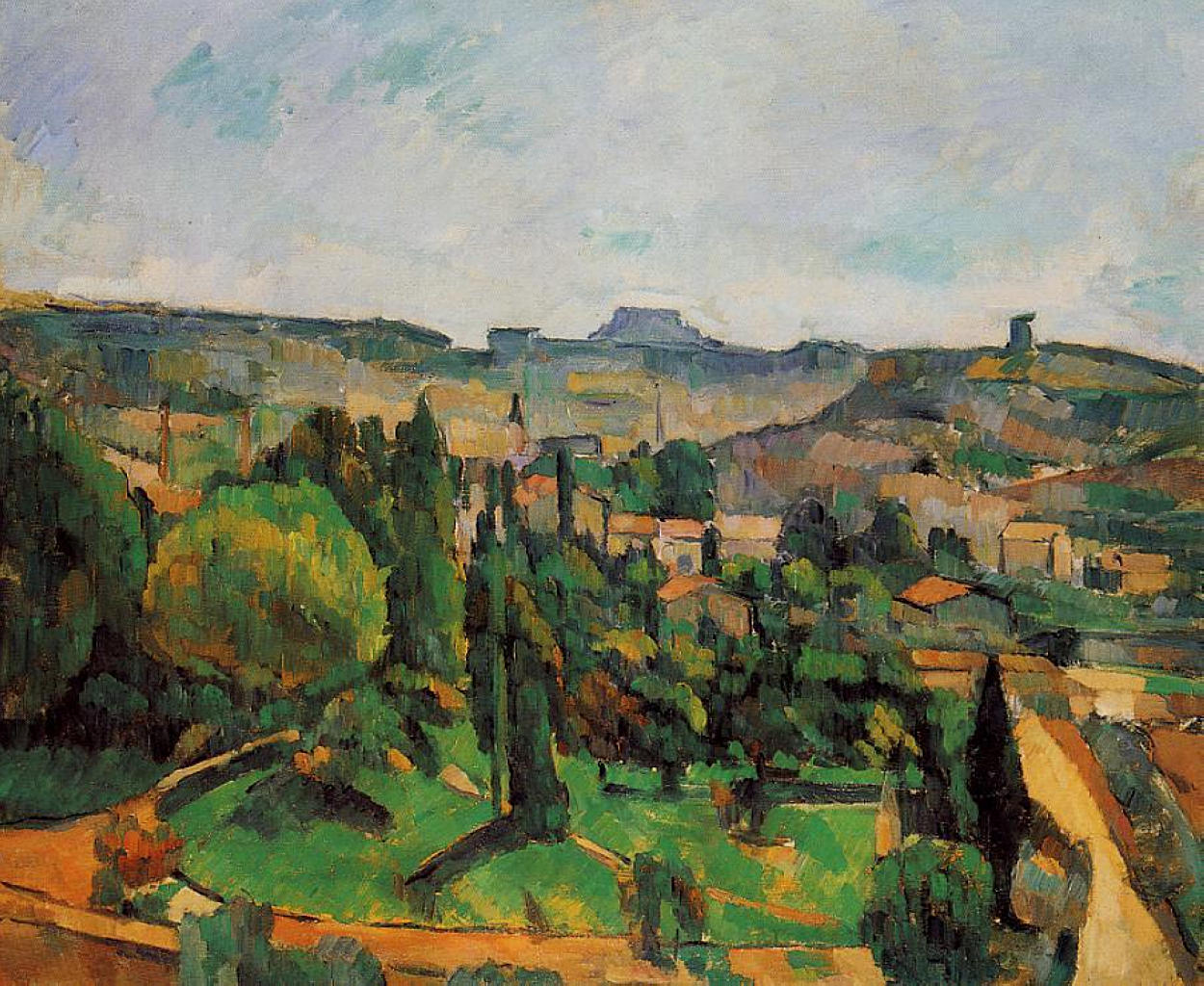

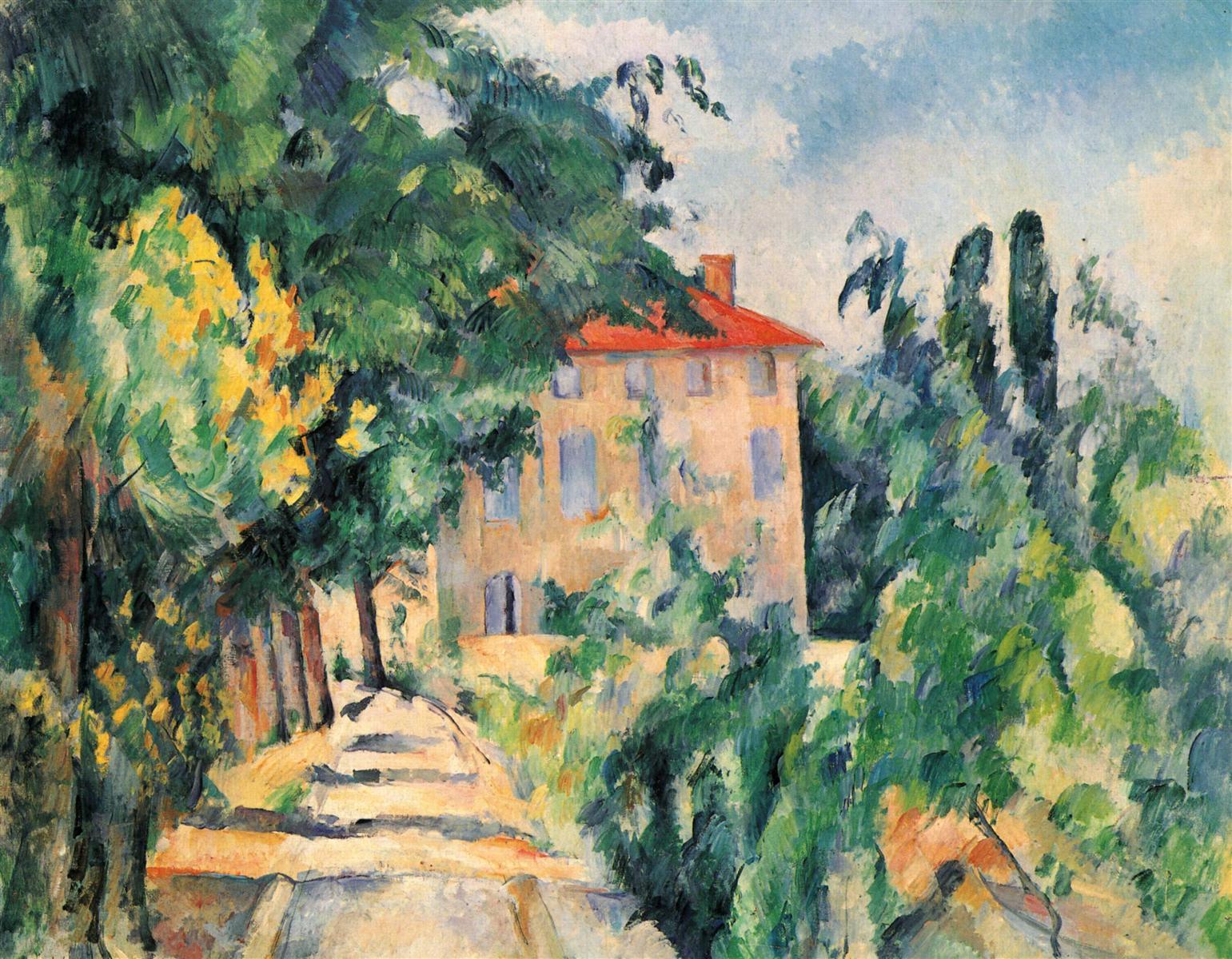

But Rilke’s landscapes made of words are pure, breathtaking magic. I SEE how his words arise from a synergy with Cézanne’s color planes — and I did my best to share my vision with you with the paintings included in this letter.

I do see, but cannot even remotely understand.

SEEING PRACTICE: BORN LANDSCAPE (INDESCRIBABLE REALITY)

Between Cézanne’s colors and Rilke’s words, the landscape itself — any landscape — anything that arises, be it in your vision or mine, turns into a work of art.

I sometimes pause to remember this: these “born landscapes” pass in front of our eyes every single moment, and each is utterly unique. There never has been, nor will ever be, this exact constellation of light, point of view, and the spectator’s unique sense of vision. This work of art arises with the generosity of a born landscape, and disappears to give birth to another one; most of them unnoticed, unseen.

These landscapes are gifts from Nature, and from countless generations of artists that shaped and expanded our sense of vision. All one has to do is RECEIVE these abundant gifts.