And how great this watching of his was, and how unimpeachably accurate, is almost touchingly confirmed by the fact that, without even remotely interpreting his expression or presuming himself superior to it, he reproduced himself with so much humble objectivity, with the unquestioning, matter-of-fact interest of a dog who sees himself in a mirror and thinks: there’s another dog.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

OCTOBER 23, 1907

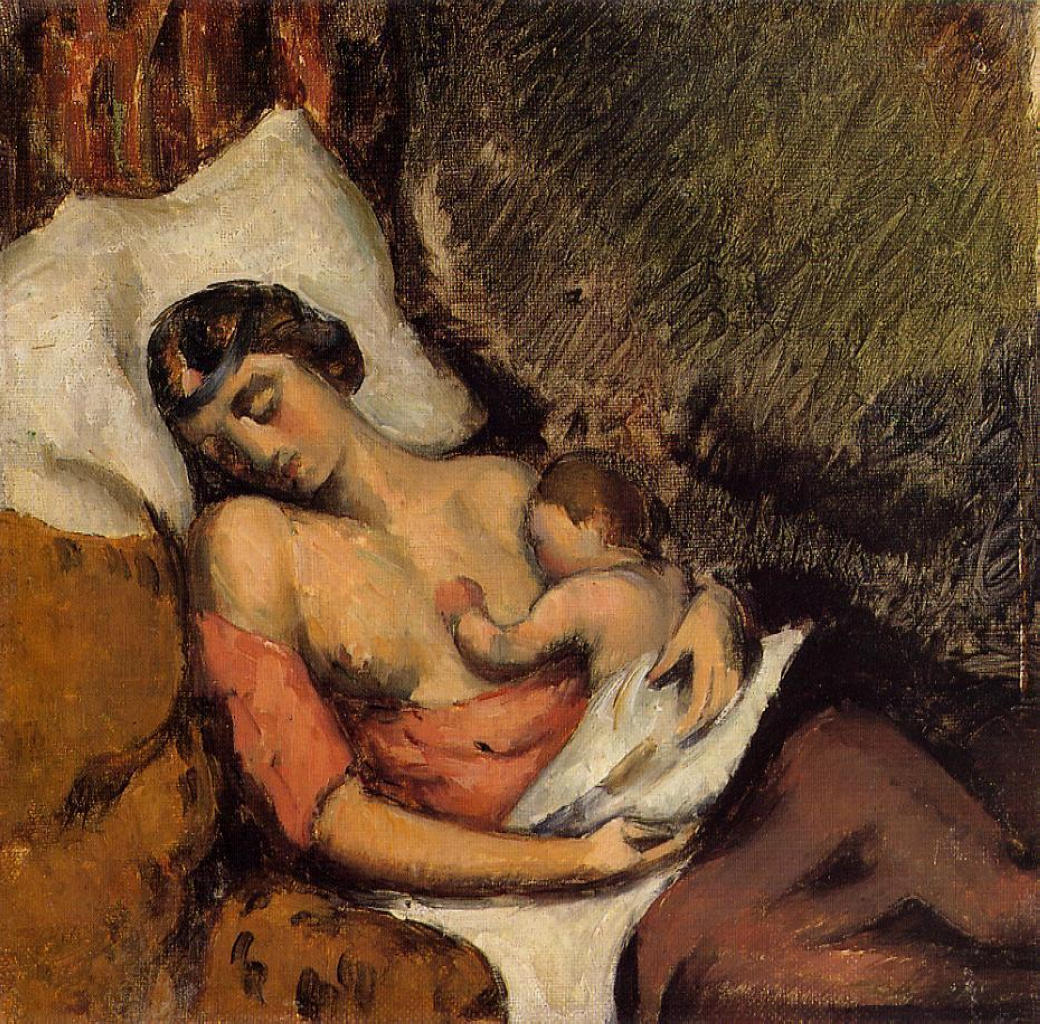

I wondered last night whether my attempt to give you an impression of the woman in the red armchair was at all successful.

I’m not sure that I even managed to describe the balance of its tonal values; words seemed more inadequate than ever, indeed inappropriate; and yet it should be possible to make compelling use of them, if one could only look at such a picture as if it were part of nature—in which case it ought to be possible to express its existence somehow.

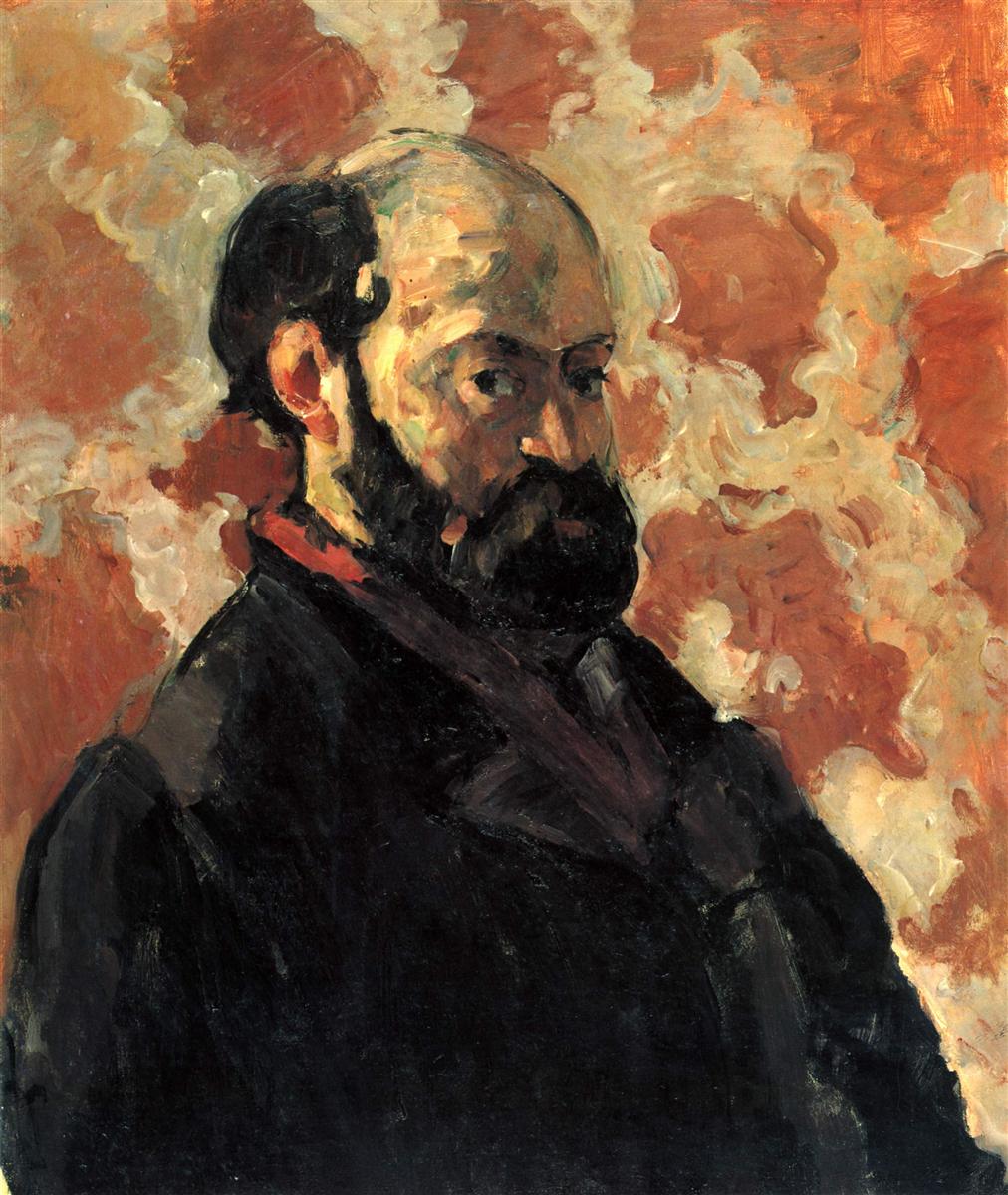

For a moment it seemed easier to talk about the self-portrait; apparently it’s an earlier work, it doesn’t reach all the way through the whole wide-open palette, it seems to keep to the middle range, between yellow-red, ocher, lacquer red, and violet purple.

In the jacket and hair it goes all the way to the bottom of a moist -violet brown contending against a wall of gray and pale copper. But looking closer, you discover the inner presence of light greens and juicy blues, which intensify the reddish tones and define the lighter areas more precisely.

In this case, however, the object as such is more tangible, and the words, which feel so unhappy when made to denote purely painterly facts, are only too eager to return to themselves in the description of the man portrayed, for here’s where their proper domain begins.

His right profile is turned by a quarter in the direction of the viewer, looking.

The dense dark hair is bunched together at the back of the head and lies above the ears so that the whole contour of the skull is exposed; it is drawn with eminent assurance, hard and yet round, the brow sloping down and of one piece, its firmness prevailing even where, dissolved into form and surface, it is merely the outermost contour containing a thousand others.

The strong structure of this skull which seems hammered and sculpted from within is reinforced by the ridges of the eyebrows; but from there, pushed forward toward the bottom, shoed out, as it were, by the closely bearded chin, hangs the face, hangs as if every feature had been suspended individually, unbelievably intensified and yet reduced to utter primitivity, yielding that expression of uncontrolled amazement in which children and country people can lose themselves,—except that the gazeless stupor of their absorption has been replaced by an animal alertness which entertains an untiring, objective wakefulness in the unblinking eyes.

And how great this watching of his was, and how unimpeachably accurate, is almost touchingly confirmed by the fact that, without even remotely interpreting his expression or presuming himself superior to it, he reproduced himself with so much humble objectivity, with the unquestioning, matter-of-fact interest of a dog who sees himself in a mirror and thinks: there’s another dog.

Fare well … for now; perhaps you can see in all this a little of the old man, who deserves the epithet he applied to Pissarro: humble et colossal. Today is the anniversary of his death …

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

STORYLINE: The work

Rilke draws an interesting triangle here, between Reality (or “facts”), Colors (painting), and Words (language). Colors and Words are alternative means of portraying Reality, but they are also, in themselves, parts of Reality.

In his description of the portrait of Mme Cézanne, he aimed to approach the painting as if it were part of nature (rather than a representation of something else). Here, he aims to describe not the painting as an independent part of reality, but rather the man represented in the painting, the reality behind the painting — and this is easier for words to do, for here’s where their proper domain begins.

But he is really describing both the painting and the reality reenacted in it, isn’t he?

SEEING PRACTICE: Cézanne

For Rilke, the reality portrayed in the painting seems much more tangible here than in the portrait of Mme Cézanne (I include it below again for the sake of comparison). And for him, this intangibility of the object being portrayed is a sign of Cézanne’s growth as an artist, of the turning point in the evolution of art.

Do you see what he means?