And (like van Gogh) [Cézanne] makes his “saints” out of such things; and forces them—forces them—to be beautiful, to stand for the whole world and all joy and all glory, and doesn’t know whether he has persuaded them to do it for him.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

OCTOBER 9, 1907 (Part 4)

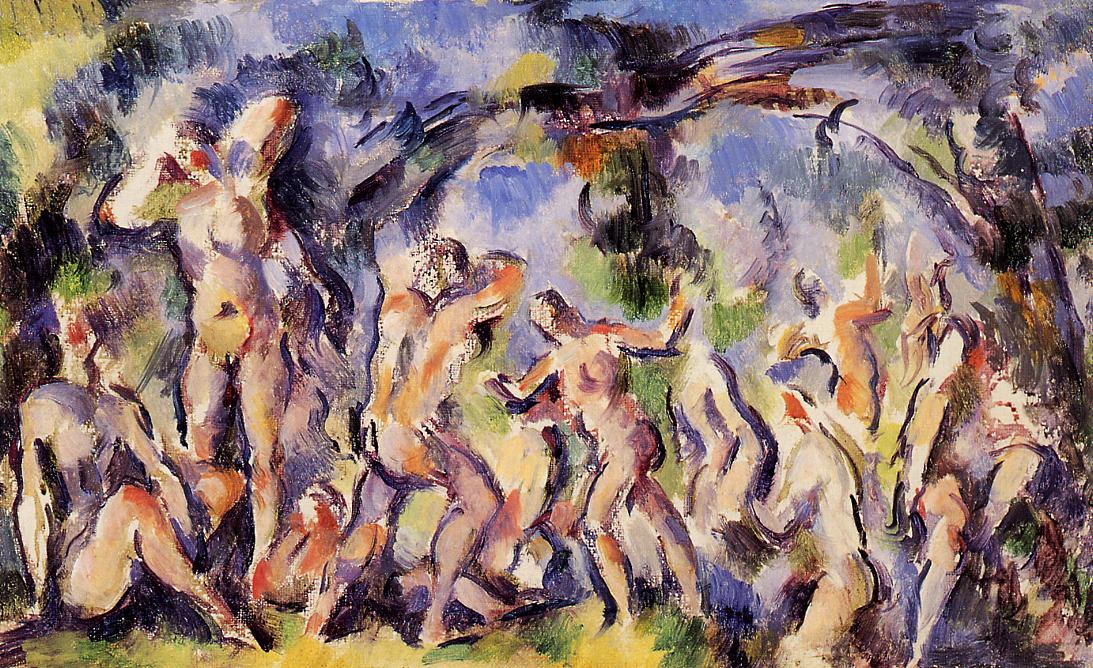

… Out there, something vaguely terrible on the increase; a little closer by, indifference and mockery, and then suddenly this old man in his work, painting nudes only from old sketches he had made forty years ago in Paris, knowing that Aix would not allow him a model.

“At my age,” he says—“I couldn’t get a woman below fifty at best, and I know it wouldn’t even be possible to find such a person in Aix.” So he uses his old drawings as models.

And lays his apples on bed covers which Madame Brémond will surely miss some day, and places a wine bottle among them or whatever he happens to find. And (like van Gogh) makes his “saints” out of such things; and forces them—forces them—to be beautiful, to stand for the whole world and all joy and all glory, and doesn’t know whether he has persuaded them to do it for him.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

SEEING PRACTICE: THINGS as Saints

Rilke returns to the idea of making “saints” out of simple things, like van Gogh, as though forgetting that this is actually his own idea. Van Gogh wanted to paint saints, or people-as-saints.

That everything he painted became as-saints: this is pure Rilke.

So is it the artists — van Gogh, Cézanne, Rilke — that make “saints” out of things, and “force” them to be beautiful?

Or is it their essence, their inalienable quality, to be sacred, and beautiful, and joyful — and all the artist does is show us what already is, as it is?

Once we have seen them as saints in paintings, can we then, from now on, see them like this in our daily lives?