It is the turning point in these paintings which I recognized, because I had just reached it in my own work or had at least come close to it somehow, probably after having long been ready for this one thing which so much depends on.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

October 18, 1907 (Part 1)

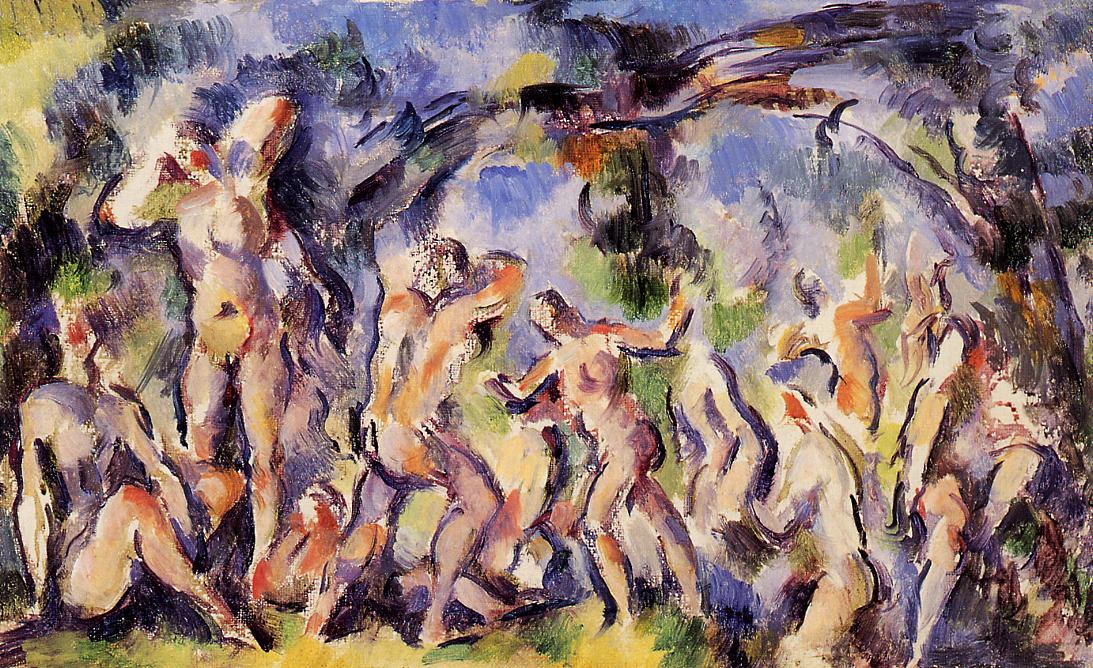

<…> I would not have been able to say how far I had developed in the direction corresponding to the immense progress Cézanne achieved in his paintings.

I was only convinced that there are personal inner reasons that allow me to see certain pictures which, a while ago, I might have passed by with momentary sympathy, but would not have revisited with increased excitement and expectation.

It’s not really painting I’m studying (for despite everything, I remain uncertain about pictures and am slow to learn how to distinguish what’s good from what’s less good, and am always confusing early with late works).

It is the turning point in these paintings which I recognized, because I had just reached it in my own work or had at least come close to it somehow, probably after having long been ready for this one thing which so much depends on.

That’s why I must be careful in trying to write about Cézanne, which of course tempts me greatly now.

It’s a mistake (and I have to acknowledge this once and for all) to think that one who has such private access to pictures is for that reason justified in writing about them; their fairest judge would surely be the one who could quietly confirm them in their existence without experiencing in them anything more or different than facts.

But within my life, this unexpected contact, the way it came and established a place for itself, is full of confirmation and relevance.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

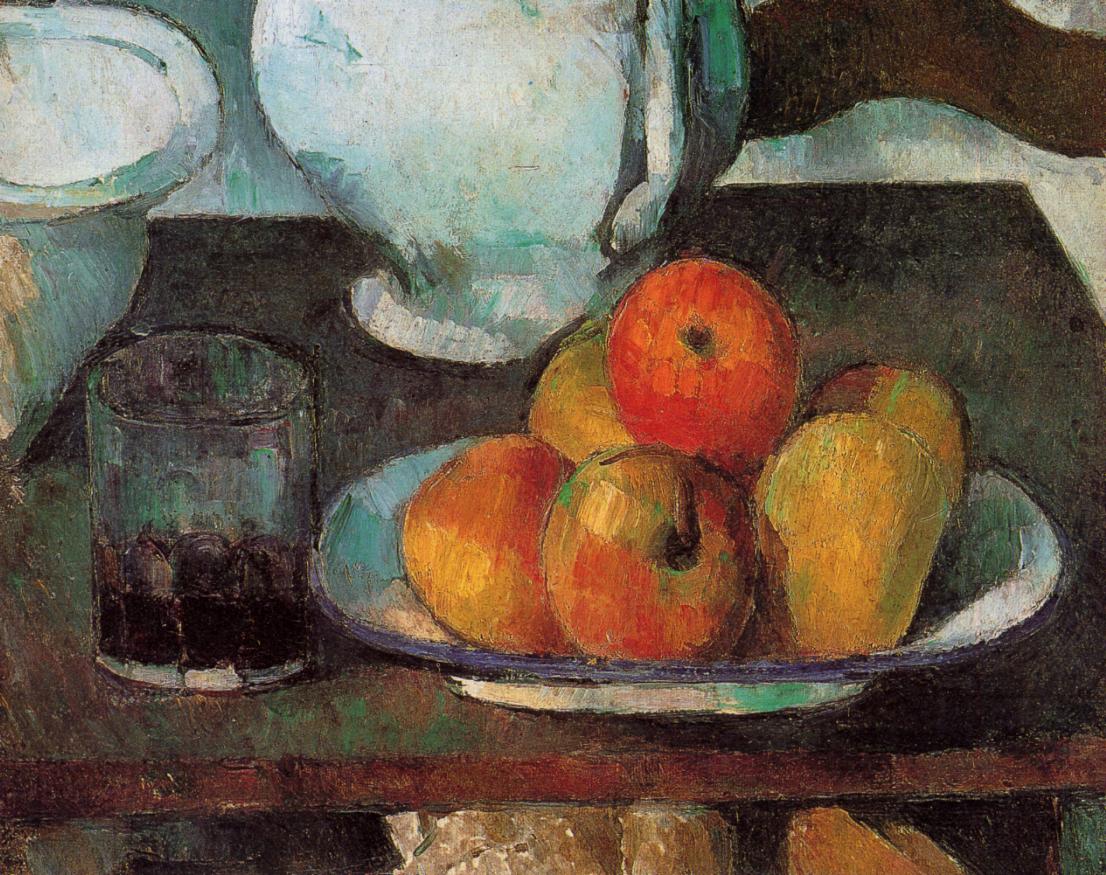

Storyline: limitless objectivity

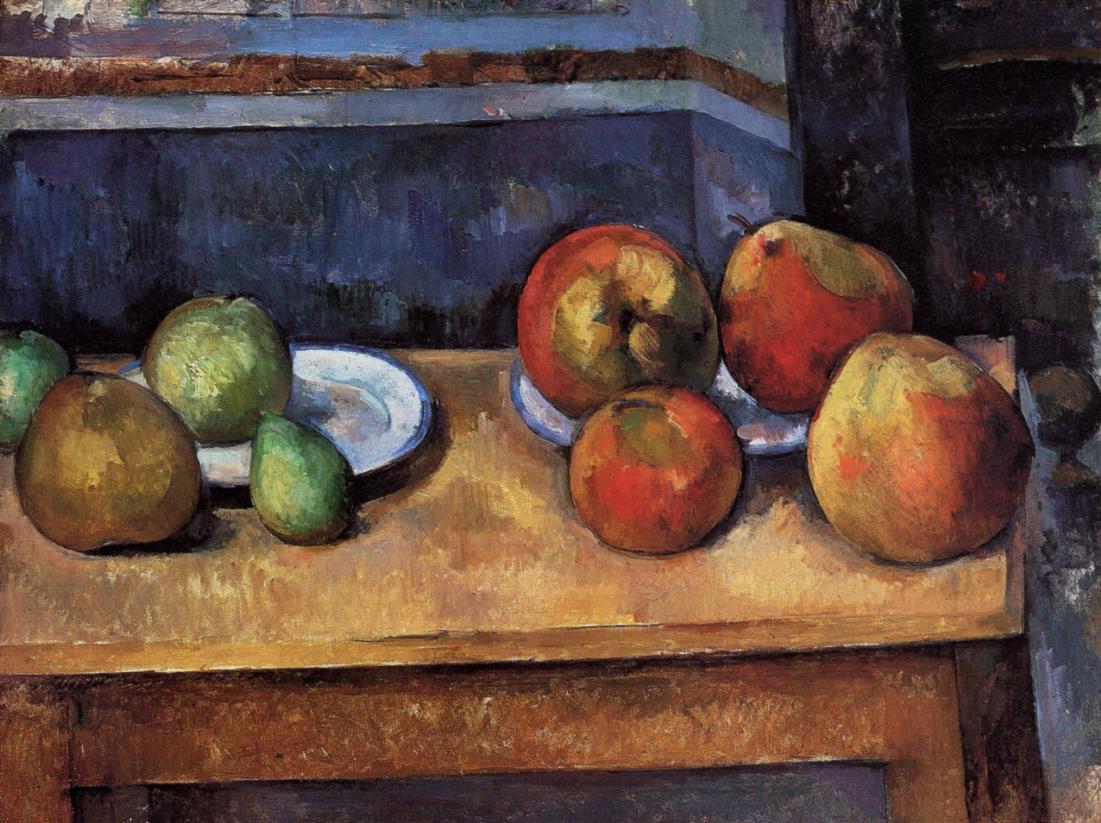

The turning point Rilke feels in Cézanne, and in himself, is the point of LIMITLESS OBJECTIVITY (he will write more about it later on).

Here, it emerges in opposition to his own subjective experience of Cézanne, his “private access”.

But is it possible to see a work of art as an objective fact, without any inner “private access” to it?

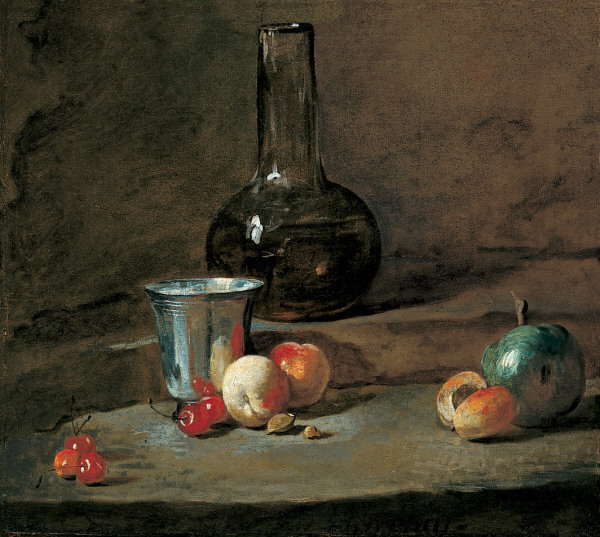

SEEING PRACTICE: SIMPLY THINGS

In the beginning of this series, I asked you to pay attention to simple things surrounding you in daily life.

Has anything changed in the way you see them?