But in his paintings (the arbre fleuri) poverty has already become rich: a great splendor from within.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

In this letter, Rilke is still under the impression of Van Gogh’s reproductions. He writes:

Would that you were sitting with me in front of the van Gogh portfolio (which I am returning with a heavy heart). It has done me so much good these two days: it was the right moment.

Isn’t that what we are doing here, trying to be with him in front of these paintings?

But this letter is as much about van Gogh’s life as it is about his paintings. Rilke recounts his biography — from his work in an art gallery, to service as an evangelical pastor, and then to being a painter, and then to madness. This is where the part of the letter included below begins…

OCTOBER 3, 1907

What a biography. Is it really true that everyone is now acting as if they understood this and the pictures that came out of it?

Shouldn’t art dealers and also art critics be really more perplexed about or else more indifferent to this dear zealot, in whom something of the spirit of Saint Francis was coming back to life?

I am surprised by his quick rise to fame. Ah, how he, too, renounced and renounced.

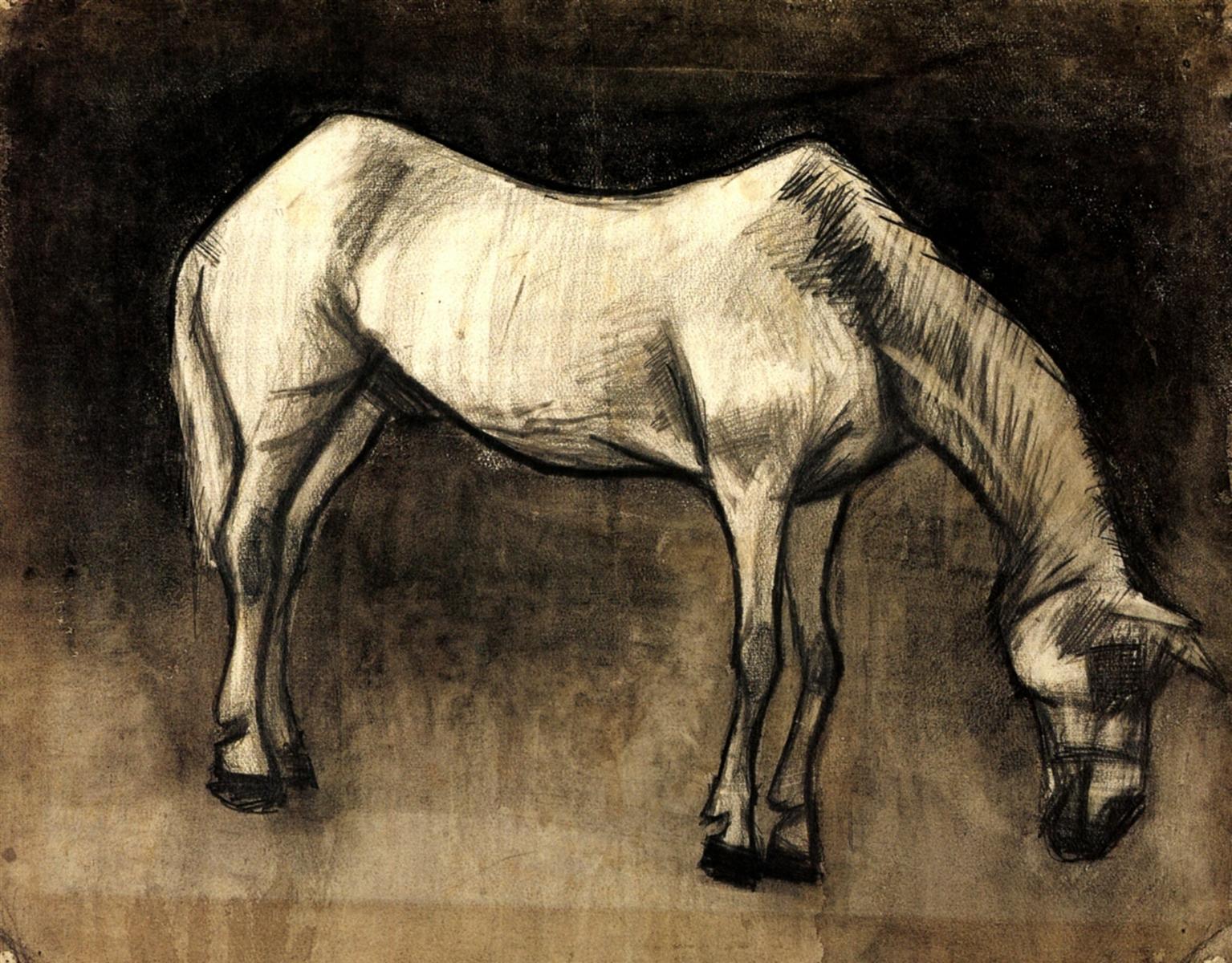

His self-portrait in the portfolio looks needy and tormented, almost desperate, but not devastated: the way a dog looks when it’s in a bad way. He holds out his face and you take note of the fact: he’s in a bad way, day and night.

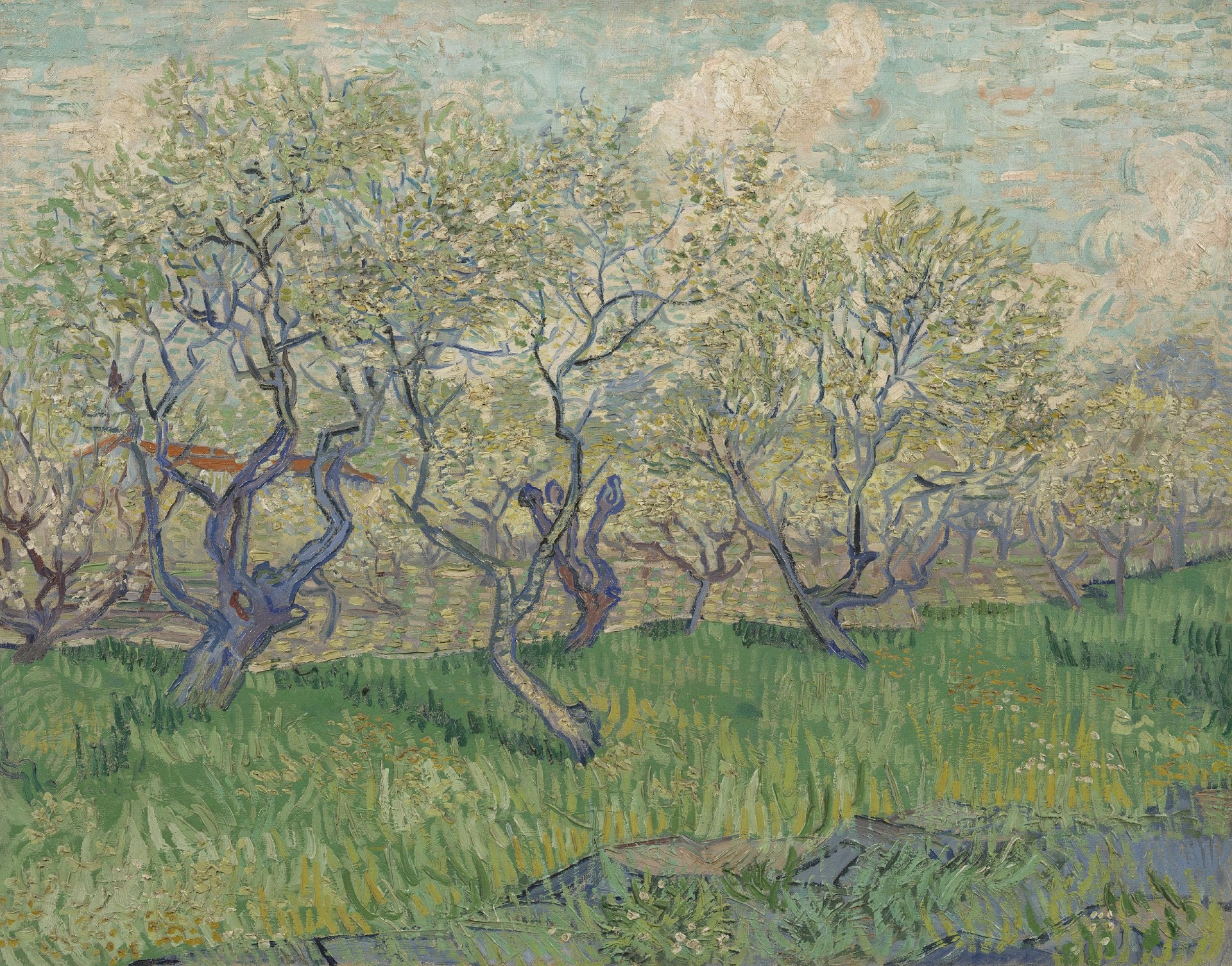

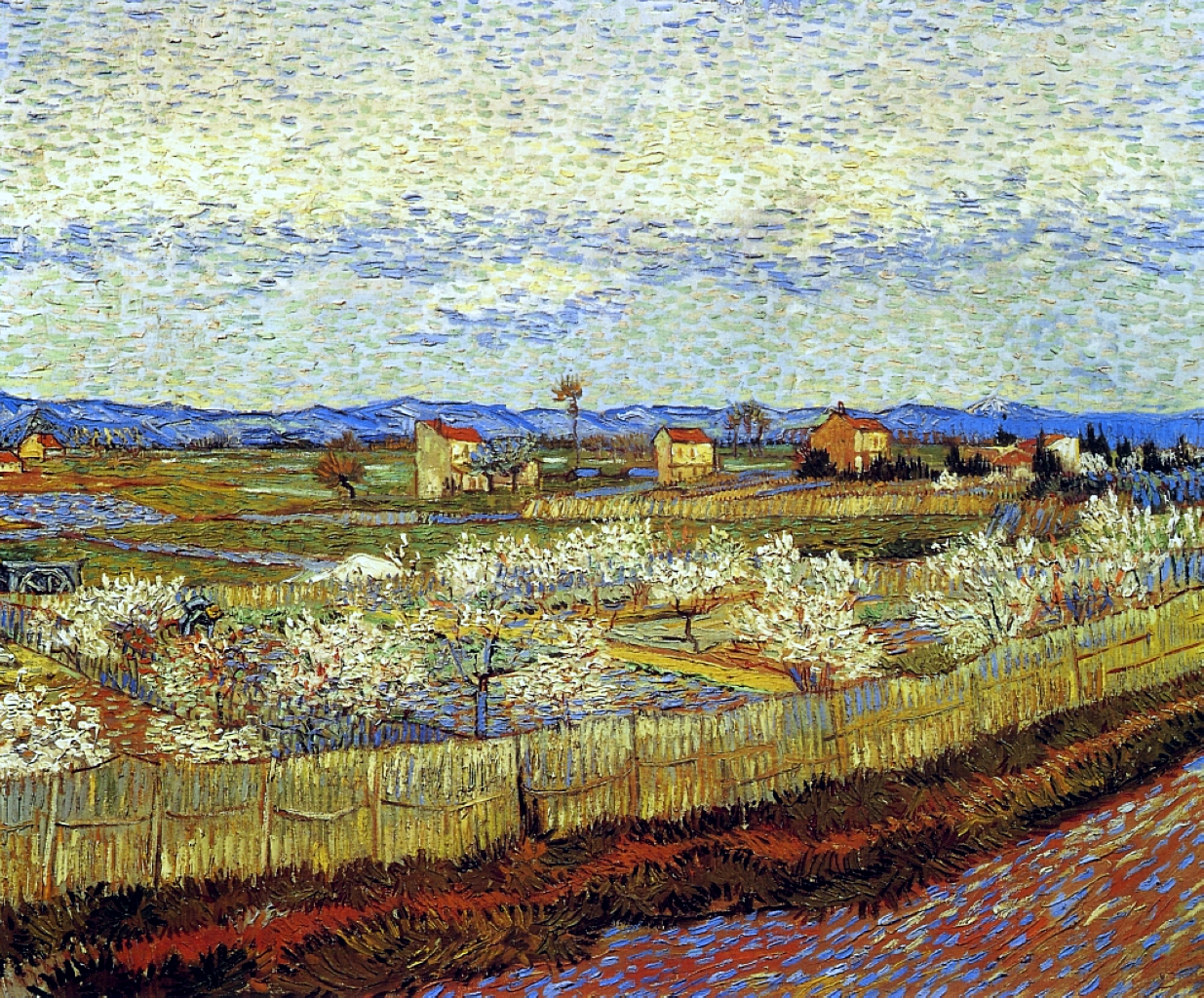

But in his paintings (the arbre fleuri) poverty has already become rich: a great splendor from within.

And that’s how he sees everything: as a poor man; just compare his parks.

These too are expressed with such quietness and simplicity, as if for poor people, so they can understand; without going into the extravagance that’s in these trees; as if to do that would already be taking sides.

He isn’t on anyone’s side, isn’t on the side of the parks, and his love for all these things is directed at the nameless, and that’s why he himself concealed it. He does not show it, he has it.

And quickly takes it out of himself and into the work, into the innermost and incessant part of the work: quickly: and no one has seen it!

That’s how one feels his presence in these forty pages: now, haven’t you been next to me after all, just a bit, in front of these pictures? …

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

STORYLINE: POVERTY. SUBJECTIVE AND OBJECTIVE

Rilke returns to the concept of poverty several times.

In this letter, it can be understood as literal, material, “real-life” poverty: the lack of money. But as this storyline unfolds, the more profound, inner meaning becomes more apparent — touching the biblical meaning of poverty as a prerequisite for reaching the kingdom of heaven.

Poverty as the lack of heritage, the lack of cultural baggage we bring to any new experience. In the modern parlance, the lack of “cognitive biases” and social conditioning.

This concept is intrinsically linked to the theme of not being “on anyone’s side”, of love being so completely spent in the act of painting that what remains is simply reality as it is.

SEEING PRACTICE: AS A POOR MAN

In my lifetime, I have certainly spent more time in front of van Gogh’s painting than Rilke did at the time he was writing this letter (if only because I am much older than Rilke was at the time).

And it would have never occurred to me to say that van Gogh sees things “as a poor man”. That is, that something in his vision is set free by his poverty. That he sees something that a rich person would never be able to see.

Can you see in van Gogh’s paintings what Rilke is writing about? More interestingly, is it possible to pause the flow of daily life and see one’s surroundings “as a poor man”, without the baggage of our possessions, our heritage, our experiences, our identities?