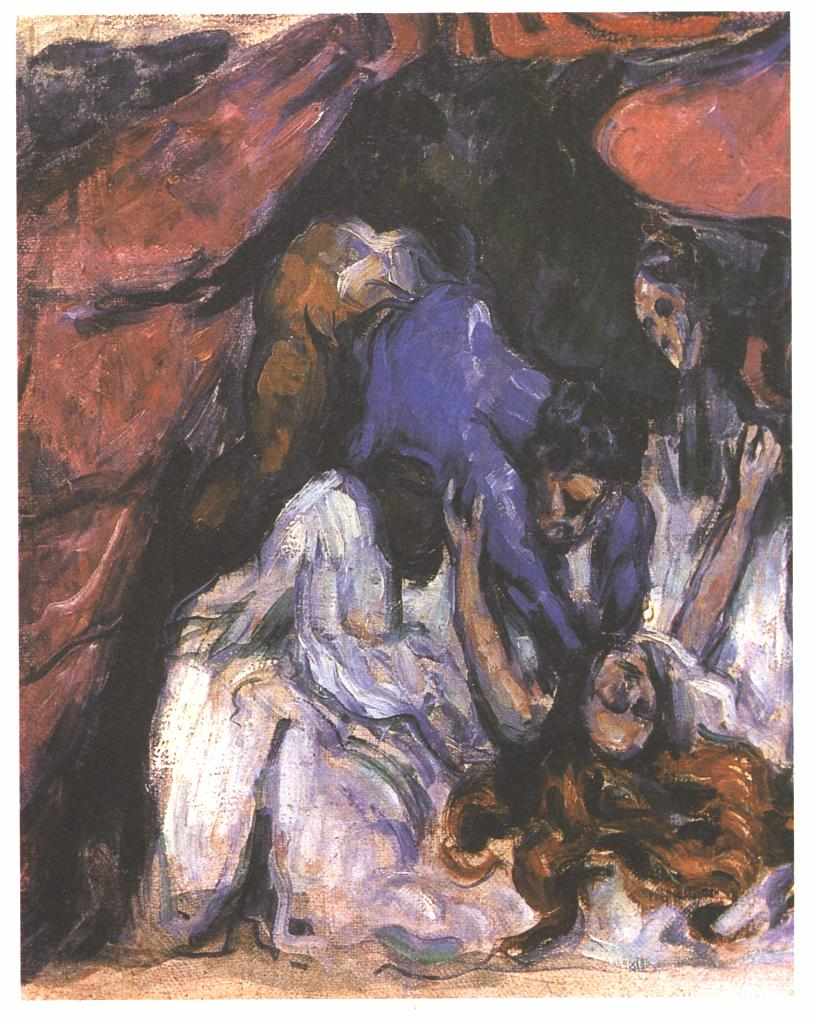

… black is treated purely as a color, not as its opposite, and is recognized again as a color among colors everywhere

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

The Salon has closed, and Rilke has left Paris for Prague, but this encounter with Cézanne isn’t over yet.

NOVEMBER 4, 1907 (Part 1)

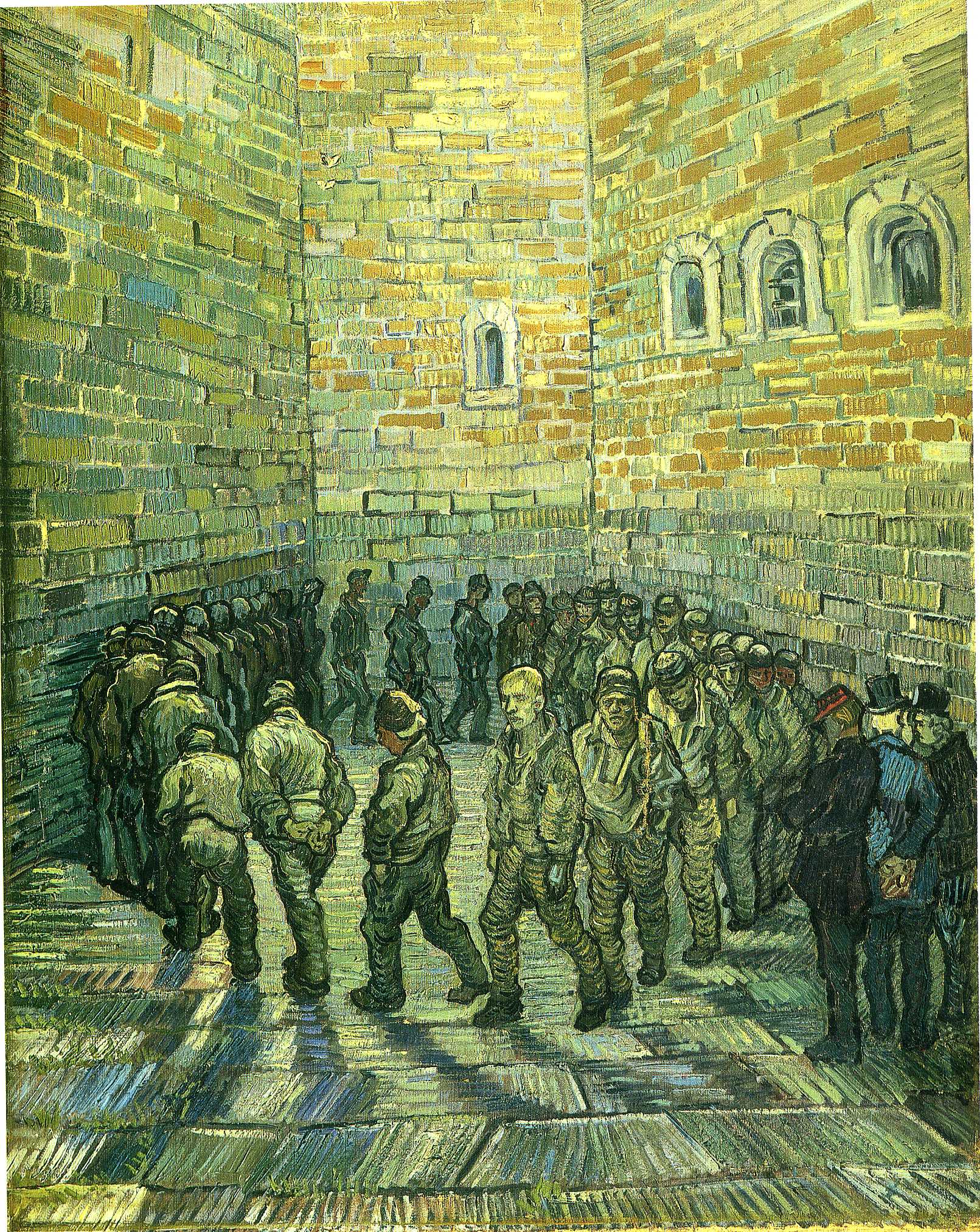

… will you believe that I came to Prague to see Cézannes? … Outside in the Manes-Pavilion, where the Rodin exhibit used to be, there was (as I fortunately learned just in time) an exhibition of modern pictures. The best and most remarkable: Monticelli and Monet well represented, Pissarro adequately; 3 things by Daumier. And 4 Cézannes. (Also van Gogh, Gauguin, Émile Bernard: each with several pieces.)

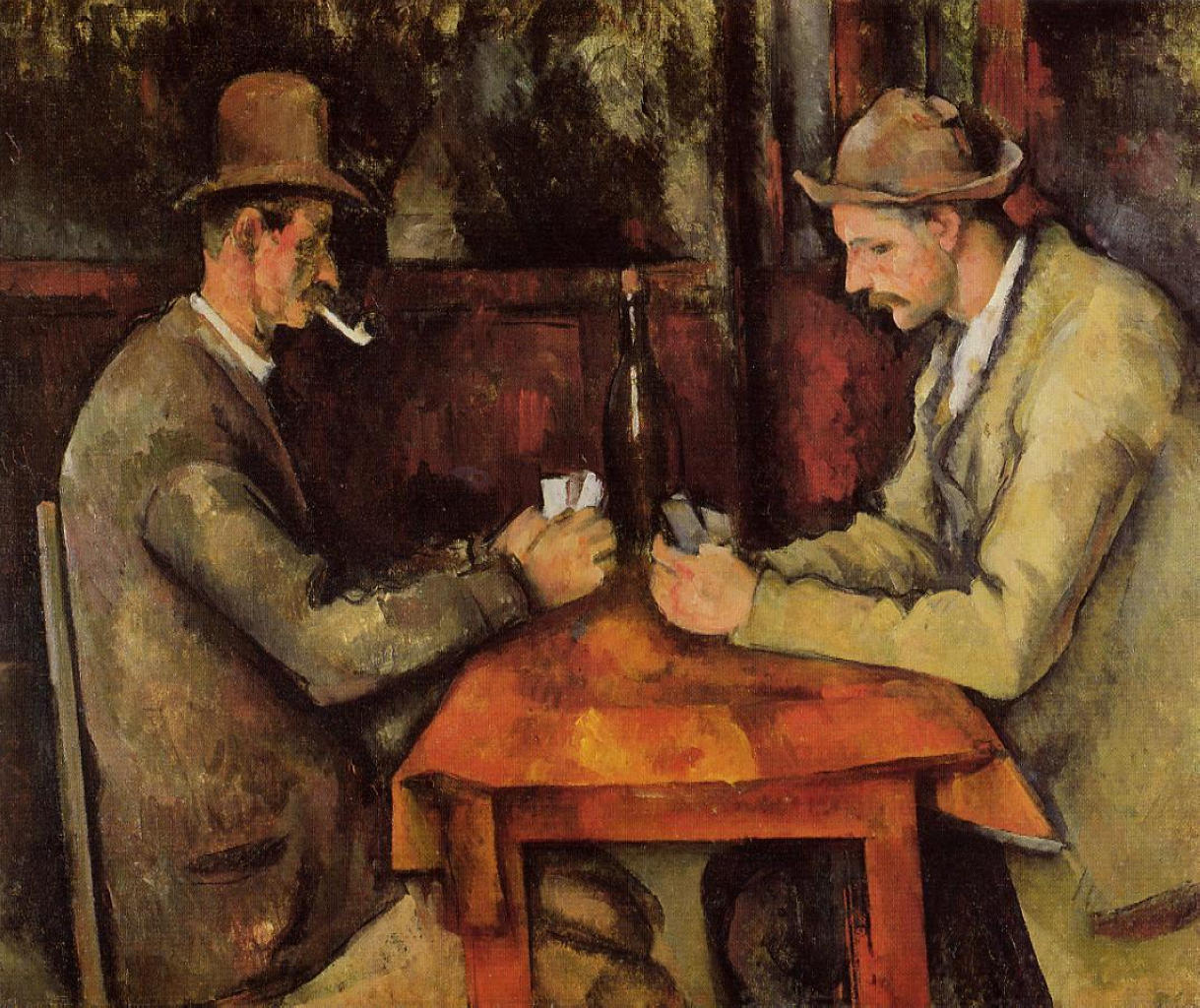

But Cézanne: a large portrait, a seated man (M. Valabrègue) with lots of black on a lead-black ground. His face, and his fists resting on his lap below, their skin tones intensified all the way to orange, are strongly and unequivocally put there.

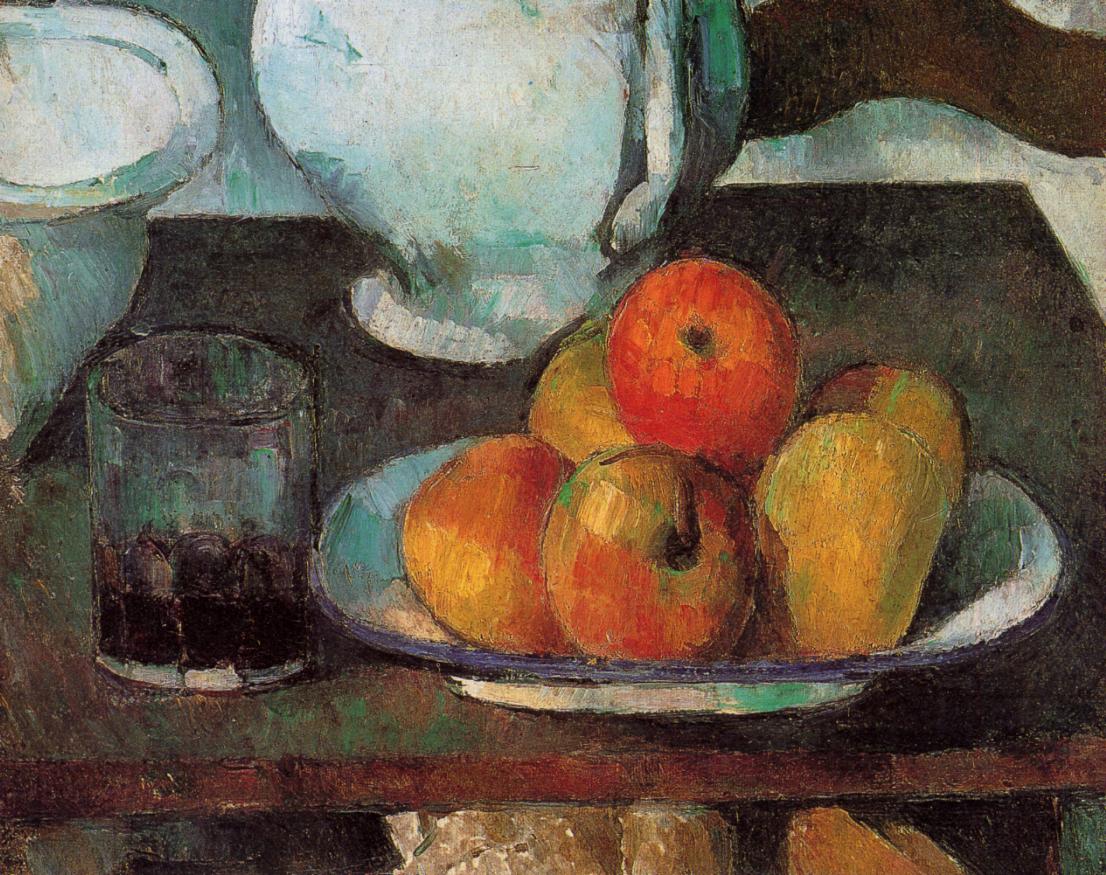

A still life, equally preoccupied with black; on a smoothly black table a long loaf of white bread in natural yellow, a white cloth, a thick-walled wine glass on a stem, two eggs, two onions, a tin milk container, and, obliquely resting against the loaf, a black knife.

And here, even more than in the portrait, black is treated purely as a color, not as its opposite, and is recognized again as a color among colors everywhere: in the cloth, over whose white it is spread, inside the glass, muting the white of the eggs and weighting the yellow of the onions to old gold.

(Just as, without having quite seen this yellow yet, I surmised that there must have been black with it.)

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

Intercourse of Colors. Color Black. Reality

Isn’t it strange and wonderful, how the unfolding of life brings us exactly what we need (or at least it does if we pay attention)?

Not just more of Cézanne, but the miraculous continuation of the theme which both opens and closes his encounter with Cézanne in Paris: the color black.

And so, as this sequence of letters draws to its close, I ask you once again to pay attention to this mysterious color, which is both a color and the absence of it, depending on how we look at it.

There is a hidden, not fully open, parallel, between seeing black as color and “realizing that even something horrible, something that seems no more than disgusting, is, and is valid, along with everything else that is”.