… they plant themselves for a moment, without looking, next to one of those touchingly tentative portraits of Madame Cézanne, so as to exploit the hideousness of this painting for a comparison which they believe is so favorable to themselves.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

OCTOBER 16, 1907 (Part 1)

Human beings, how they play with everything.

How blindly they misuse what has never been looked at, never experienced, distract themselves by displacing all that has been immeasurably gathered together <…>

You have only to see the people going through the two rooms, say on a Sunday: amused, ironically irritated, annoyed, indignant. And when they finally arrive at some concluding remark, there they stand, these Monsieurs, in the middle of this world, affecting a note of pathetic despair, and you hear them saying: il n’y a absolument rien, rien, rien.

And the women, how beautiful they appear to themselves as they pass by; they recall that just a little while ago they saw their reflections in the glass doors as they stepped in, with complete satisfaction, and now, with their mirror image in mind, they plant themselves for a moment, without looking, next to one of those touchingly tentative portraits of Madame Cézanne, so as to exploit the hideousness of this painting for a comparison which they believe is so favorable to themselves.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

SOLITUDE

The further one goes along one’s own path, living the experience all the way to the end, the more solitary the journey.

This letter touches two aspects of the artist’s solitude.

One is obvious: the general public’s inability to see what has been shown, to hear what has been said, if it is too radically new, to far removed from their habituated experiences.

The other is hardly mentioned, but it is there nonetheless. It is invoked by Rilke’s mention of the portraits of Mme Cézanne.

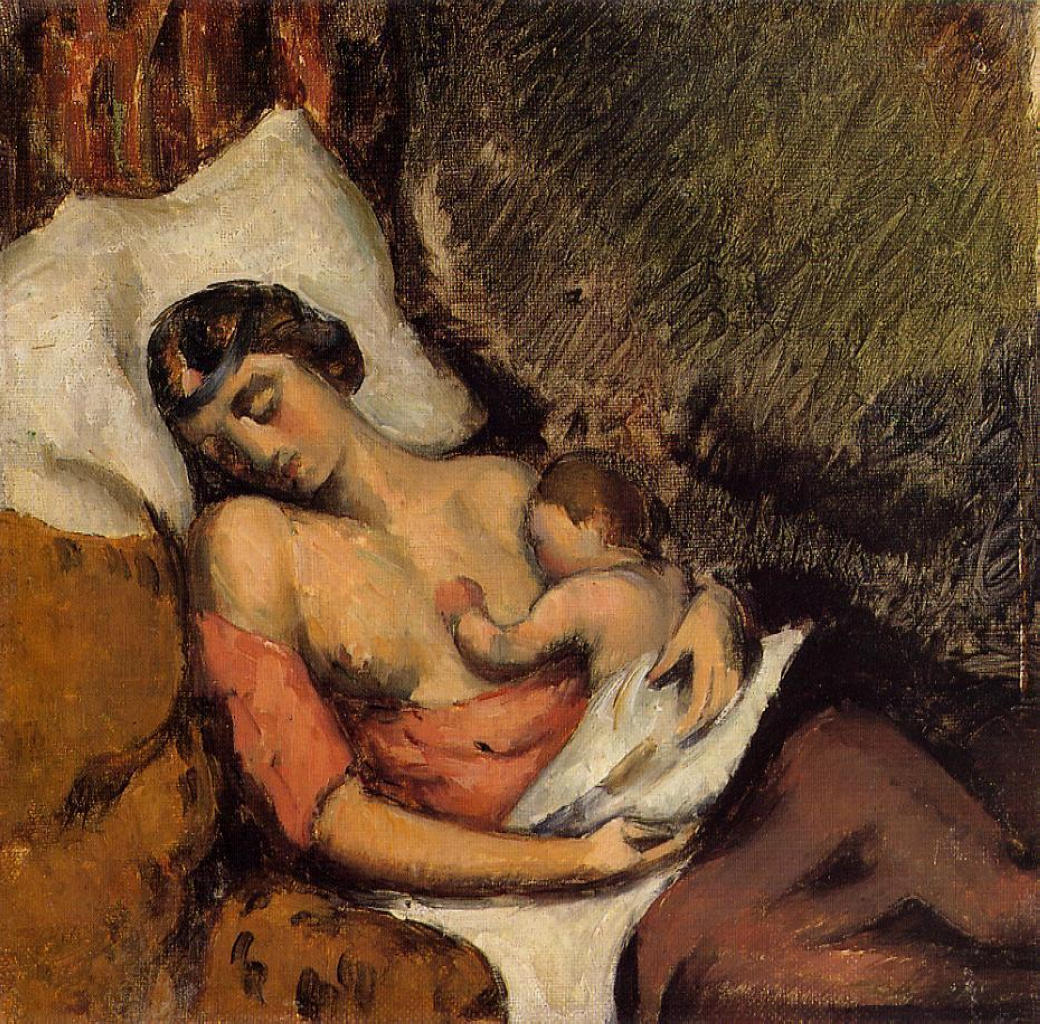

SEEING PRACTICE: Portraits of Hortense Fiquet-Cézanne

Cézanne met his future wife, Hortense Fiquet (1850– 1922) in Paris in 1869 (he was thirty years old at the time). Their son, Paul, was born in 1872, but Cézanne had to keep the relationship secret for a long time for fear of being disowned by his father. They married (and Paul was legitimized) only in 1886.

Alex Danchev writes in a note to The Letters of Paul Cézanne:

It is widely believed that she and Cézanne did not have much in common, apart from their son, and that soon enough she came to mean rather little to him.

Against that prejudiced account should be set at least twenty-four portraits, painted over a period of twenty years, long after they had ceased to live together all the time.

Cézanne studied his wife more intently and more durably than he did anyone else, except perhaps himself, to extraordinary effect.

My own experience of these portraits has changed dramatically over time.

As a young girl, all I saw in them was radical objectification. They were painted, I thought, as though there were no interpersonal relationship there, as though he didn’t see a human being in her at all.

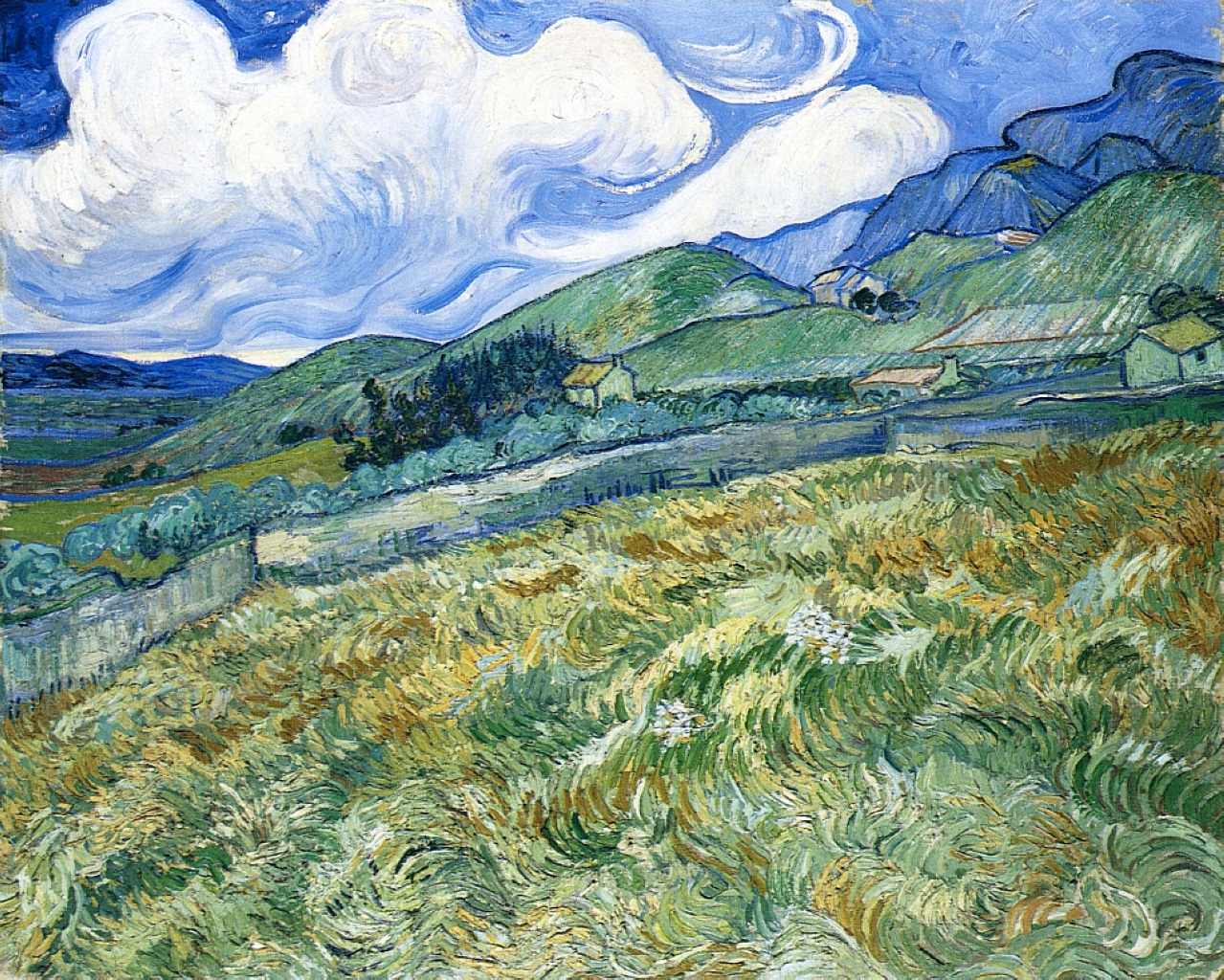

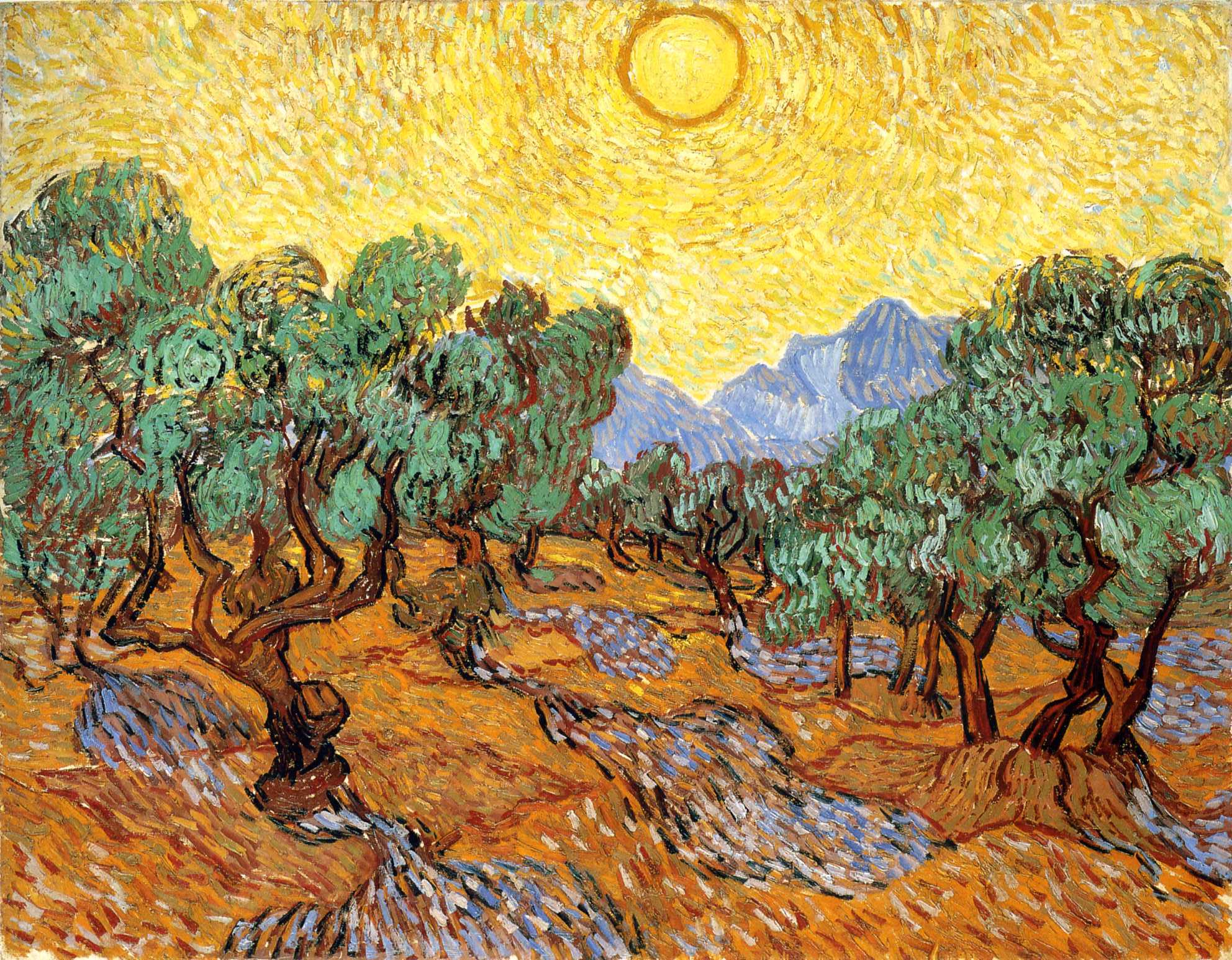

But it is not at all the kind of objectification usually meant in the context of gender relationships. He approaches and sees her in the same way he did his mountain, Mont Sainte-Victoire, and as Rilke has reportedly once remarked, “Not since Moses has anyone seen a mountain so greatly.”

While working on this project, I found a very early portrait of Hortense, which stands quite apart from the rest.

In Rilke’s words, this early portrait says: I love her. If the ladies in the Salon (or me as a young girl) saw this, we would probably have been more touched, more impressed.

But the mature ones only say: HERE SHE IS.

Let me quote from an earlier letter here again, because it is so relevant here:

They’d paint: I love this here; instead of painting: here it is.

In which case everyone must see for himself whether or not I loved it. This is not shown at all, and some would even insist that it has nothing to do with love.

The love is so thoroughly used up in the action of making that there is no residue. It may be that this using up of love in anonymous work, which produces such pure things, was never achieved as completely as in the work of this old man.