As if these colors could heal one of indecision once and for all. The good conscience of these reds, these blues, their simple truthfulness, it educates you…

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

OCTOBER 13, 1907 (Part 2)

Today I went to see his pictures again; it’s remarkable what a surrounding they create.

Without looking at a particular one, standing in the middle between the two rooms, one feels their presence drawing together into a colossal reality.

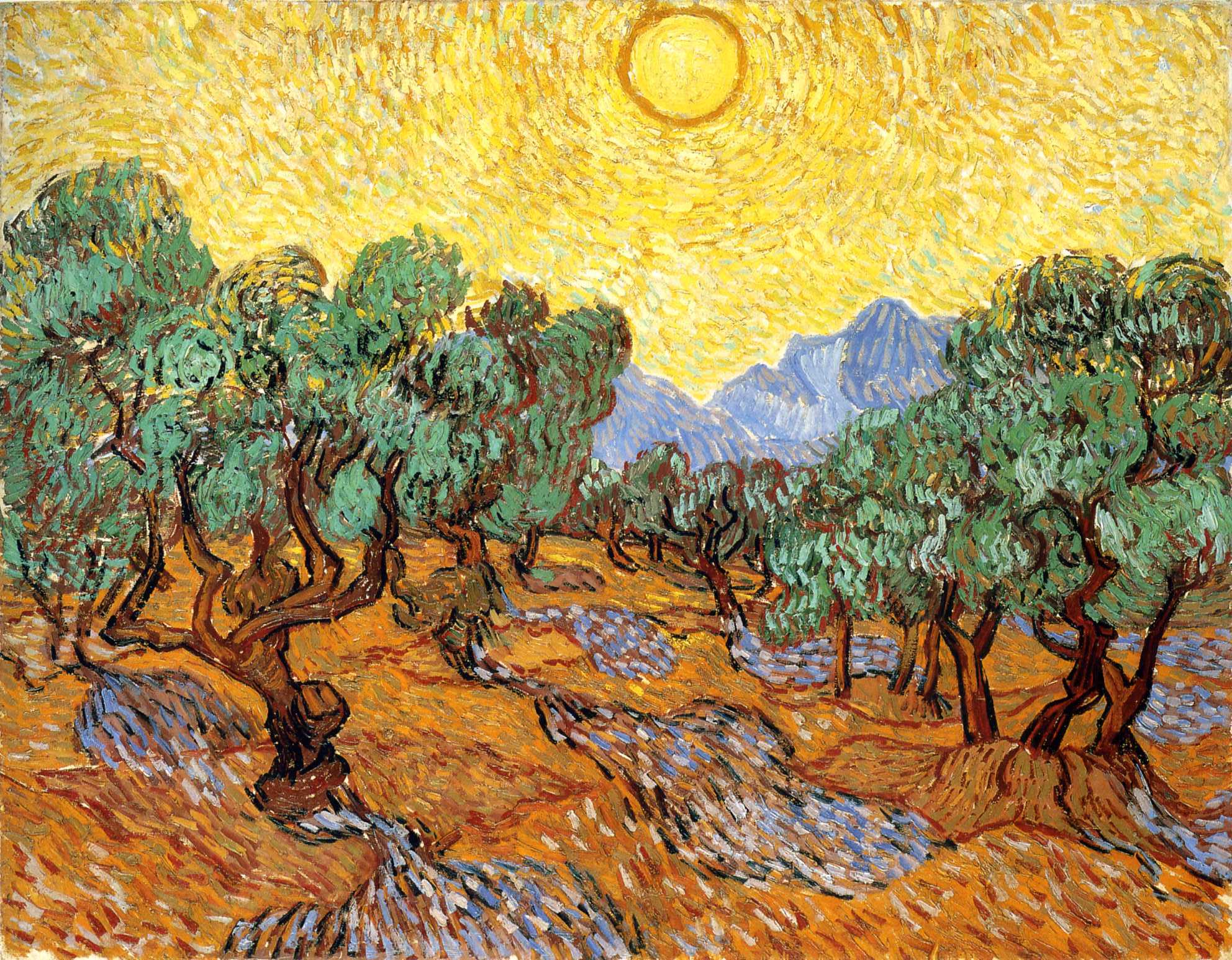

As if these colors could heal one of indecision once and for all. The good conscience of these reds, these blues, their simple truthfulness, it educates you; and if you stand among them as ready as possible, you get the impression that they are doing something for you.

You also notice, a little more clearly each time, how necessary it was to go beyond love, too; it’s natural, after all, to love each of these things as one makes it: but if one shows this, one makes it less well; one judges it instead of saying it.

One ceases to be impartial; and the best—love—stays outside the work, does not enter it, is left aside, untranslated: that’s how the painting of moods came about (which is in no way better than the painting of things).

They’d paint: I love this here; instead of painting: here it is.

In which case everyone must see for himself whether or not I loved it. This is not shown at all, and some would even insist that it has nothing to do with love.

The love is so thoroughly used up in the action of making that there is no residue. It may be that this using up of love in anonymous work, which produces such pure things, was never achieved as completely as in the work of this old man.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

THE WORK. LOVE. SUBJECTIVE AND OBJECTIVE

Isn’t it interesting, and revealing, that Rilke uses the exact same expression, “no residue”, with regard to LOVE and COLOR (in the previous letter)?

He is so decidedly on the side of painting of (and writing) THINGS, not FEELINGS. The objective, not the subjective.

If there is a place for LOVE in a work of art, it is in the process, completely used up in the making. Paradoxically, if it is intentionally expressed, it stays outside the work.

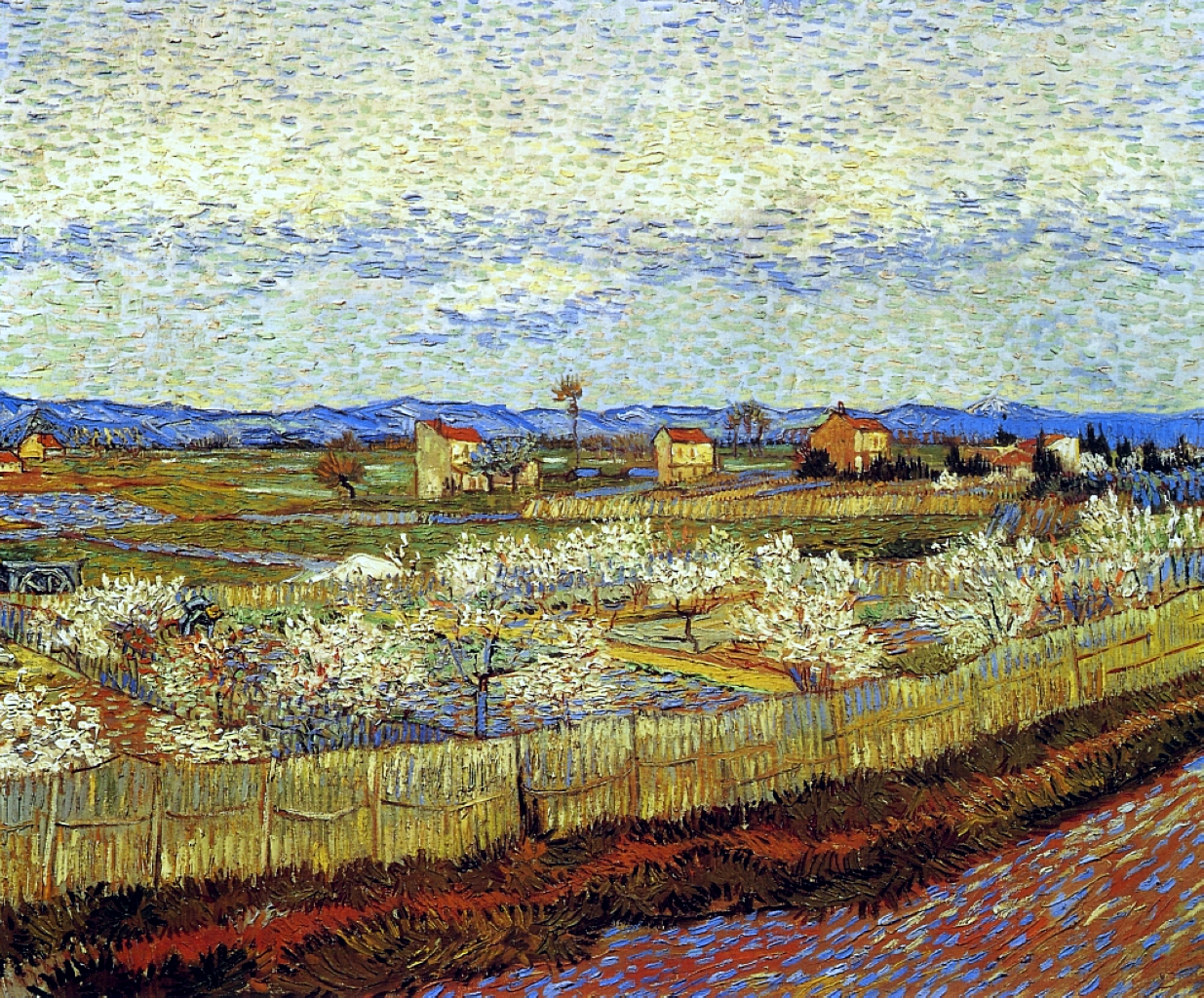

SEEING PRACTICE: CONSCIENCE OF COLOR

The good conscience of these reds, these blues, their simple truthfulness…

It is an unusual way to think about colors: do they have conscience, good or bad? Are they truthful, or false?

Or loud, pretentious, deceitful, manipulative?

It is not only about painting, it is also about colors we see daily (even as we look at the screens of our phones, or our computers).

The color of a flower, or a tree trunk, or the sky: they never lie. But what about our houses, and cars, and the visual noise of advertisements?