OCTOBER 17, 1907 (Part 5)

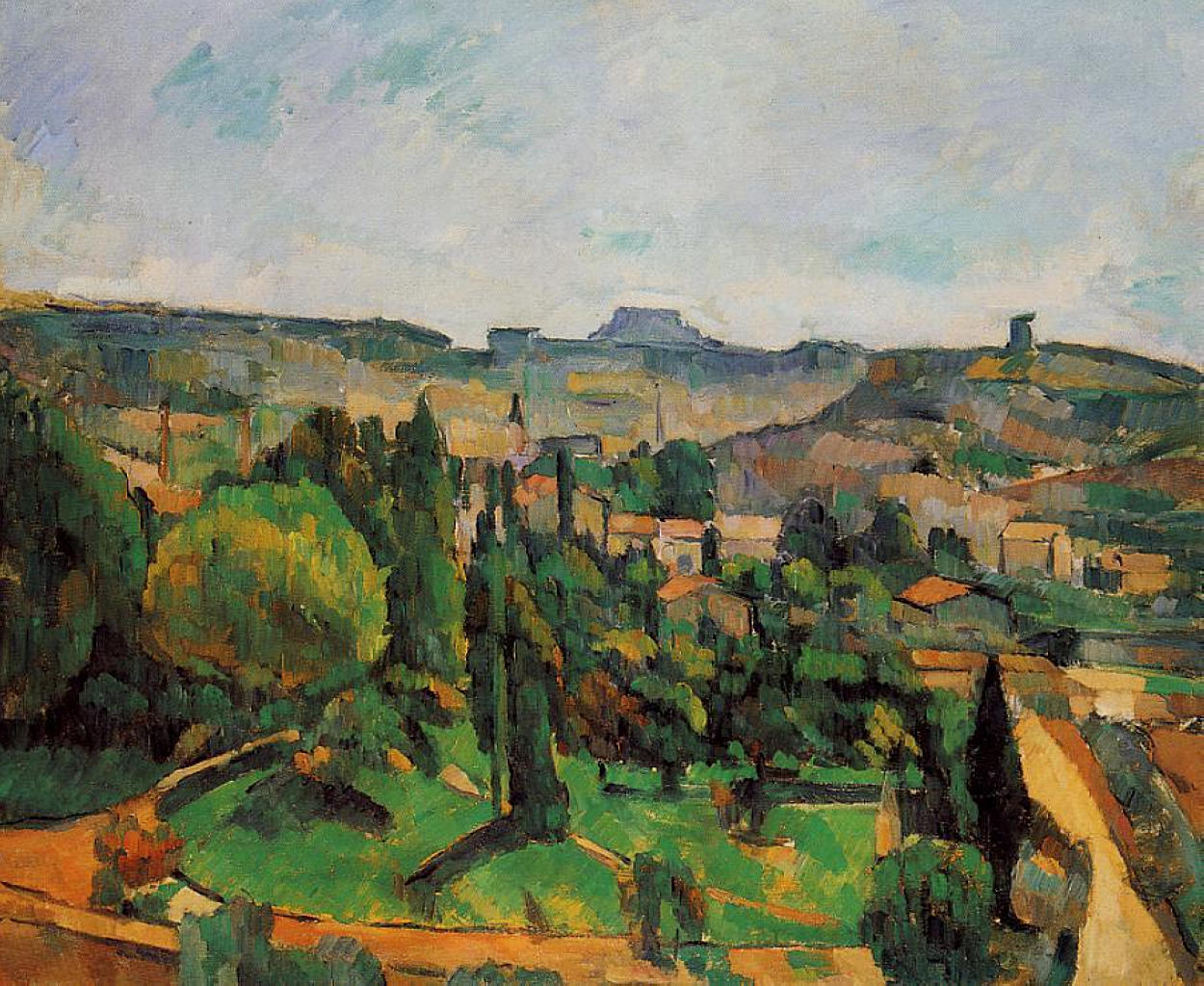

… and finally: one of those landscapes he was always postponing and yet already painting again and again:

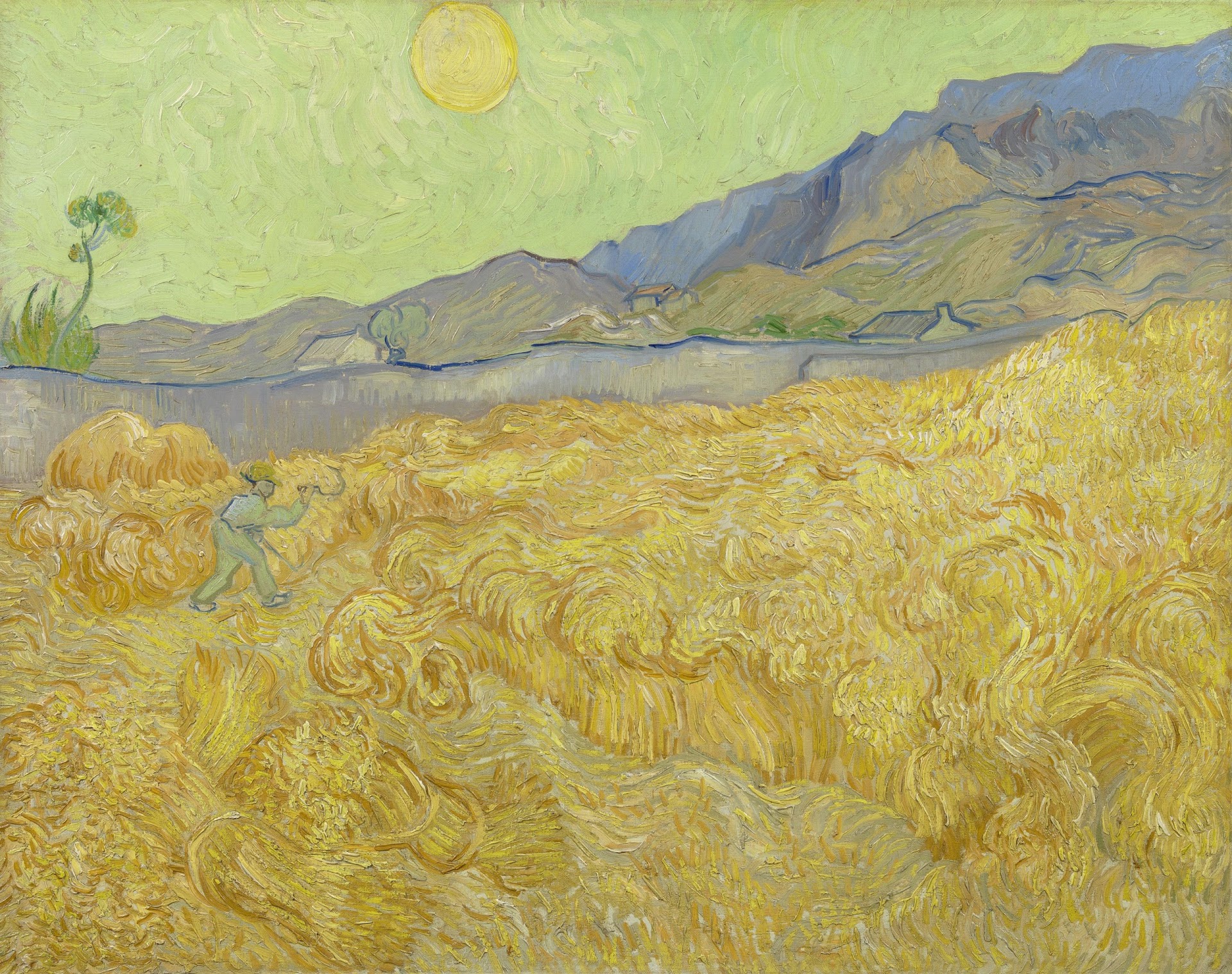

a setting sun, yellow and orange red, surrounded by its glow of yellow, round fragments.

Against it, full of revolt, Blue, Blue, Blue the slope of curved hills, separated from the twilight by a strip of assuaging pulsations (a river?), in which, transparent in dark antique gold, in the slanted front third of the picture, you can make out a field and leaning groups of upright sheafs of corn.

THE WORK

The work we are postponing, waiting for the time when we are finally ready to do it: and yet already doing it.

Rilke writes about van Gogh, but perhaps even more so, about himself.

He is postponing the work on his autobiographical novel, The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, and already writing it, in these letters. Some passages were eventually included in the book verbatim.

He is full of doubts about writing about Rodin, and yet already writing about him, too.

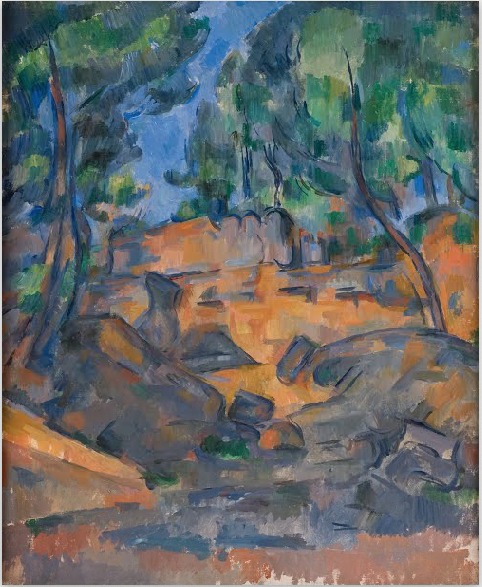

And, strikingly, as we will see soon, he doesn’t just POSTPONE, but resolves NOT to write about Cézanne… because he doesn’t consider himself qualified.

But the work gets done, in its own time and rhythm, quite oblivious to our decisions.

The best we can do is not to get in its way with our doubts and transient concerns.

SEEING PRACTICE: VAN GOGH’S indescribable reality

Yesterday, I wrote about the moment I got a glimpse of van Gogh’s visual reality in front of his self-portrait.

But even after that moment, it took a long, long time to even begin to integrate his expansion of vision into my experience of life, to finally get “the right eyes”.

It takes essentially the same practice Rilke describes in these letters: the practice of paying your full attention first to paintings, and then, with the eyes trained and cleansed by them, to the world around us.