Basically, if it is good, one can’t live to see it recognized: otherwise it’s just half good and not reckless enough …

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

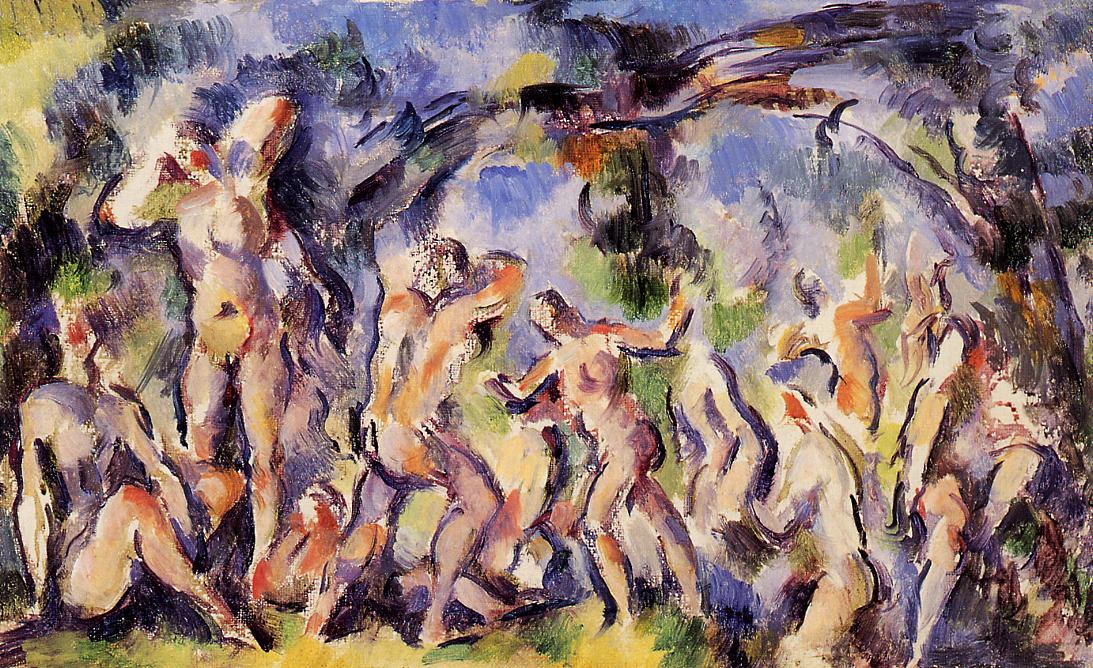

In the first part of this letter, Rilke observes visitors to the Salon, and their utter inability to see Cézanne’s work (even when it is already in the Salon, allowed and sanctified by the art world).

OCTOBER 16, 1907 (Part 2)

… One cannot expect that a time that is capable of gratifying aesthetic requirements of this order should be able to admire Cézanne and grasp anything of his devotion and hidden splendor.

The merchants make noise, that is all; and those who have a need to attach themselves to these things could be counted on the fingers of two hands, and they stand apart and are silent.

And someone told the old man in Aix that he was “famous.” He, however, knew better within himself and let the speaker continue.

But standing in front of his work, one comes back to the thought that every recognition (with very rare, unmistakable exceptions) should make one mistrustful of one’s own work.

Basically, if it is good, one can’t live to see it recognized: otherwise it’s just half good and not reckless enough …

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

THE WORK. THE OLD AND THE NEW

… if it is good, one can’t live to see it recognized: otherwise it’s just half good and not reckless enough …

These words have been playing themselves in my head for many years now, as a counterbalance to our age’s pervasive belief that if the work is not recognized, it cannot be any good. This belief is built into the very foundation of what is called “art world”: quality in art is in effect equated with the art world’s recognition of it.

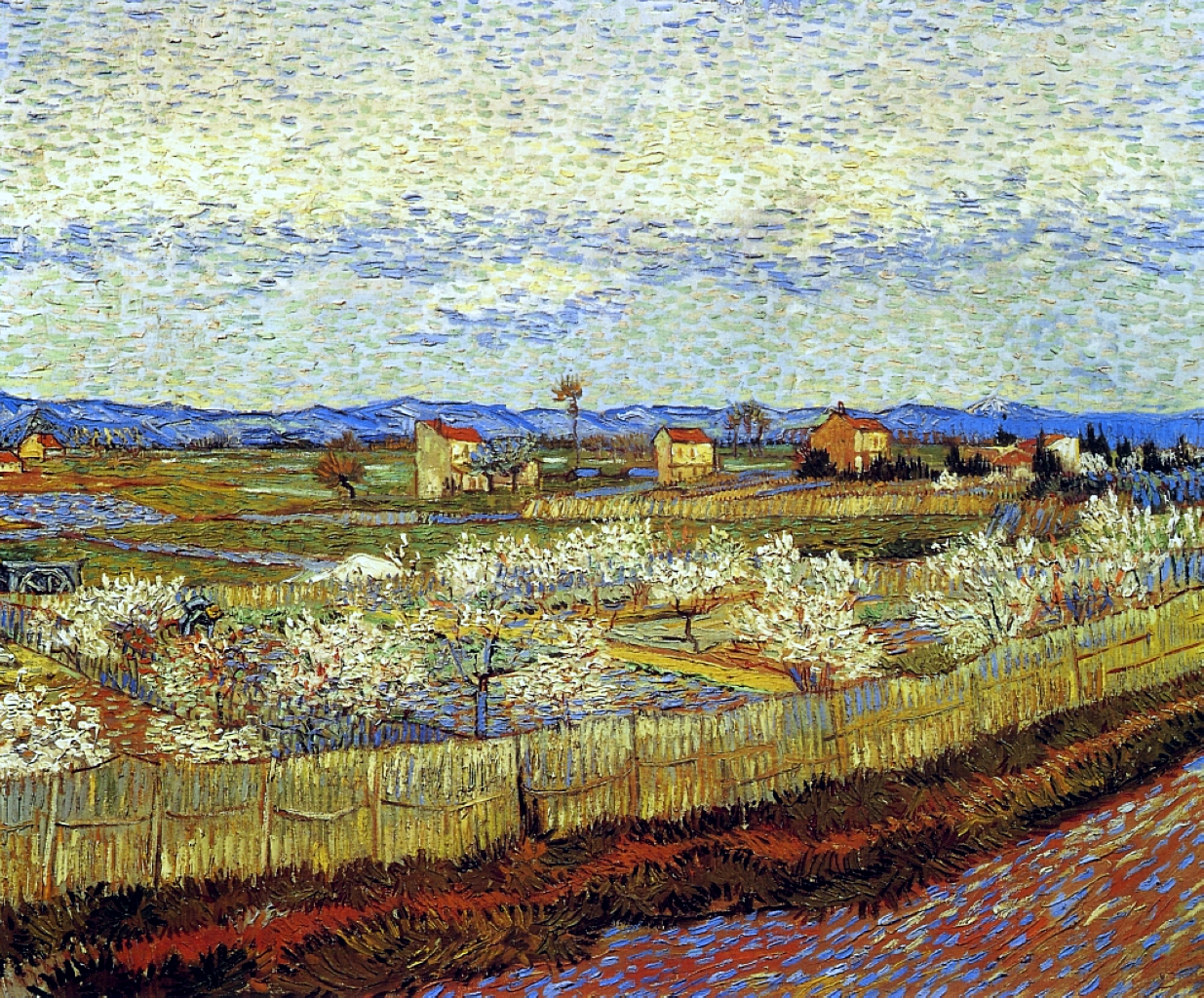

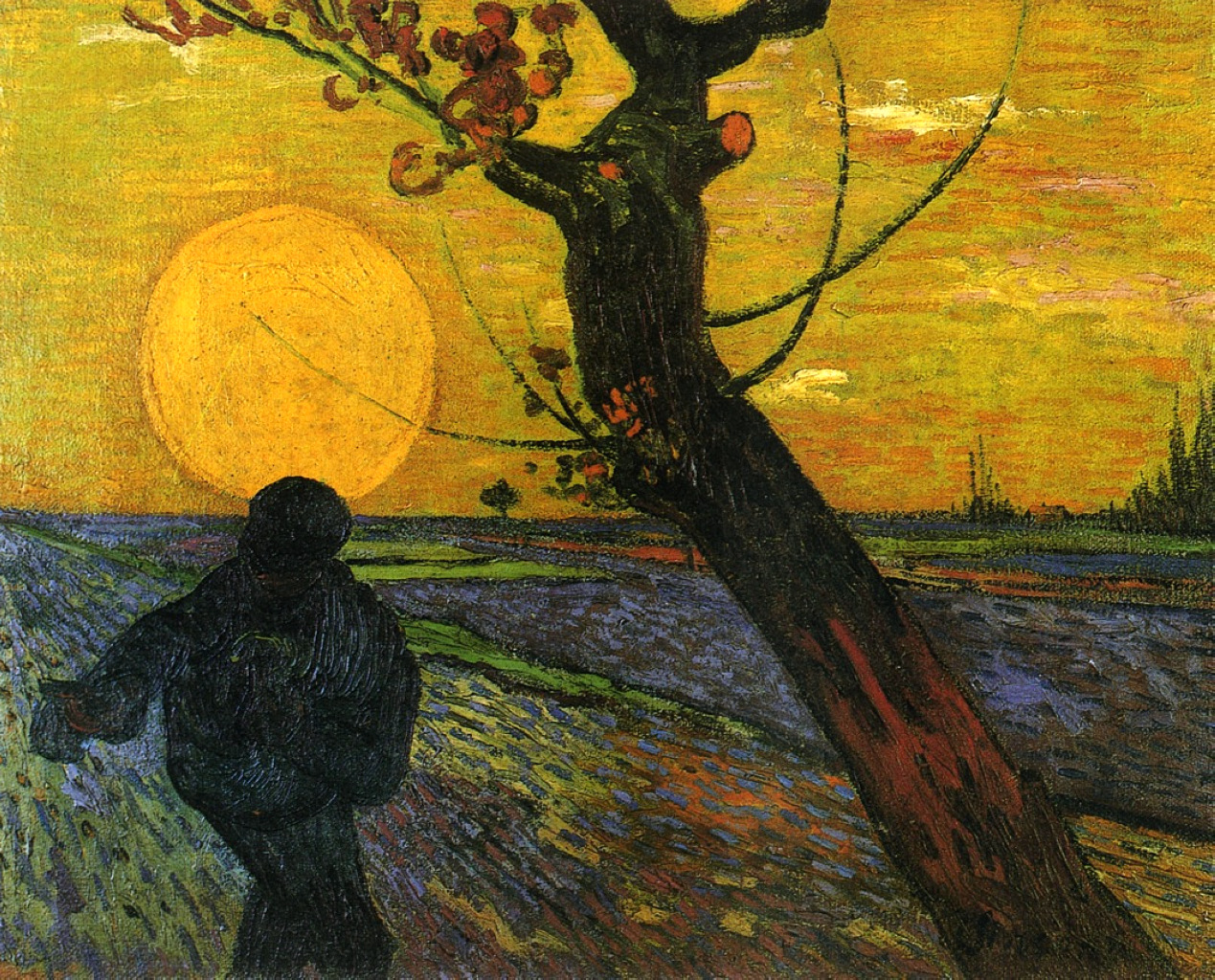

As though our age were somehow better at seeing than that of Cézanne, Monet, van Gogh, Rilke… But is it?

SEEING PRACTICE

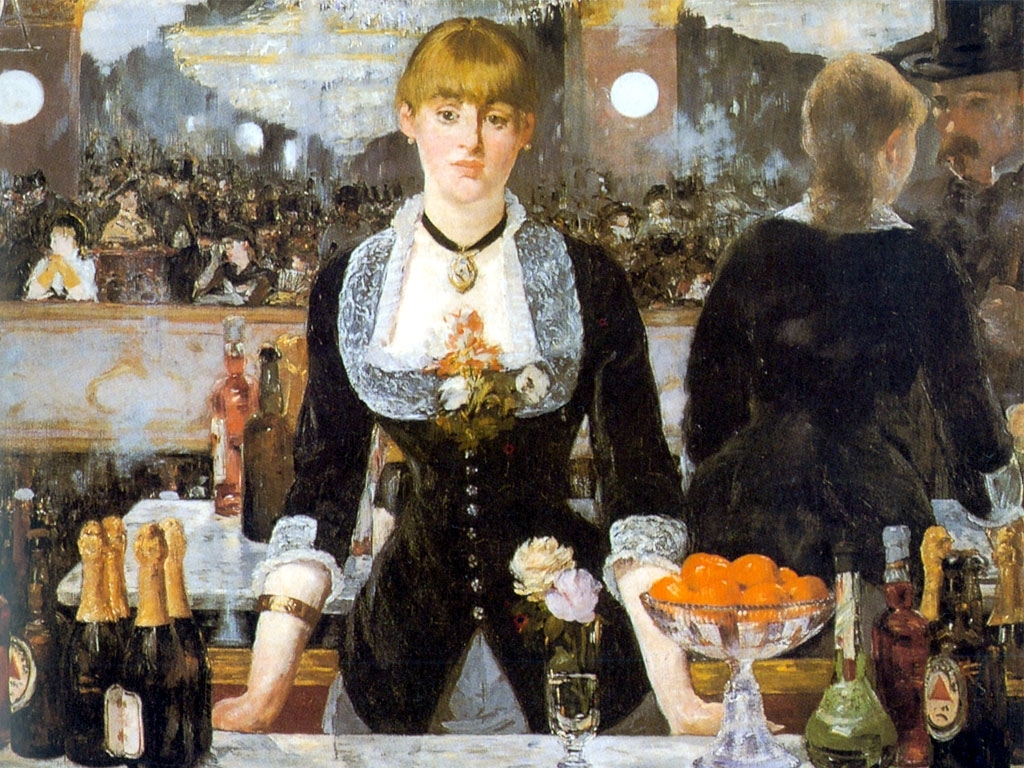

Kandinsky believed that every work of art is eventually understood. For him, that meant a lot: that the spectator partakes in the same inner experience as the artist. In Kandinsky’s own words: the spectator souls vibrates in response to the work, playing as it were the motive embodied by it.

It is not the same as “recognition”: an art work can be “officially” recognized without being truly understood.

Nowadays, Cézanne, Monet, van Gogh are as “recognized” as it gets. Their exhibitions tend to be blockbusters, so much so that tickets often have to be secured well in advance. And the public certainly behaves more respectfully than those ladies and gentlemen Rilke witnessed in 1907.

But do we truly see the paintings, do we fully understand them? Is our age capable of grasping anything of Cézanne’s devotion and hidden splendor?