… all we basically have to do is to be there, but simply, ardently, the way the earth simply is, consenting to the seasons, light and dark and altogether in space, not asking to rest upon anything other than the net of influences and forces in which the stars feel secure.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

OCTOBER 19, 1907 (Part 2)

<…> After this devotion, in small ways at first, lies the beginning of sainthood: the simple life of a love that endured; that, without ever boasting of it, approaches everything, unaccompanied, inconspicuous, wordless.

The real work, the abundance of tasks, begins, all of it, after this enduring, and whoever has not been able to come this far may well get to see the Virgin Mary in Heaven, and certain saints and minor prophets as well, and King Saul and Charles le Téméraire—:

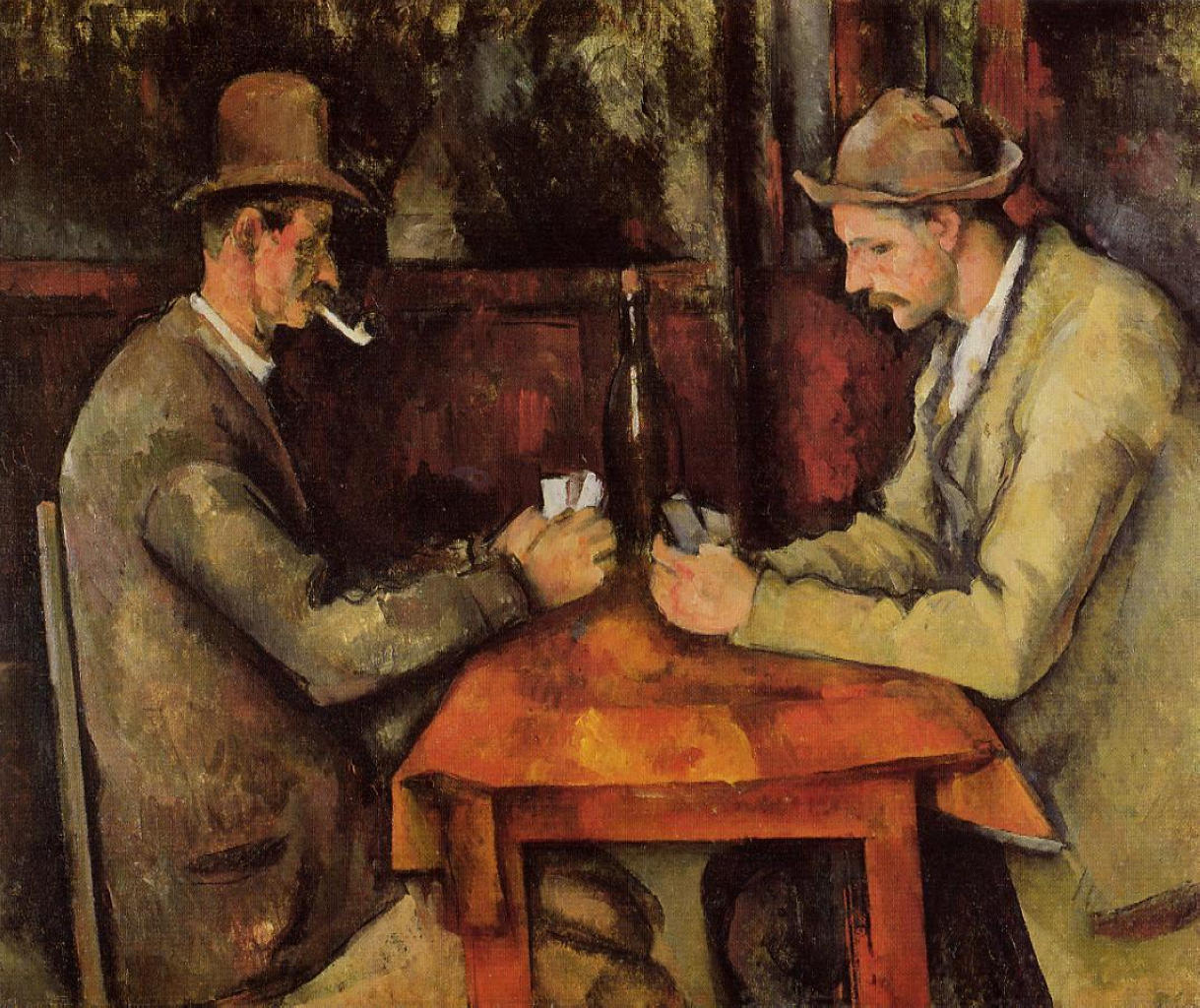

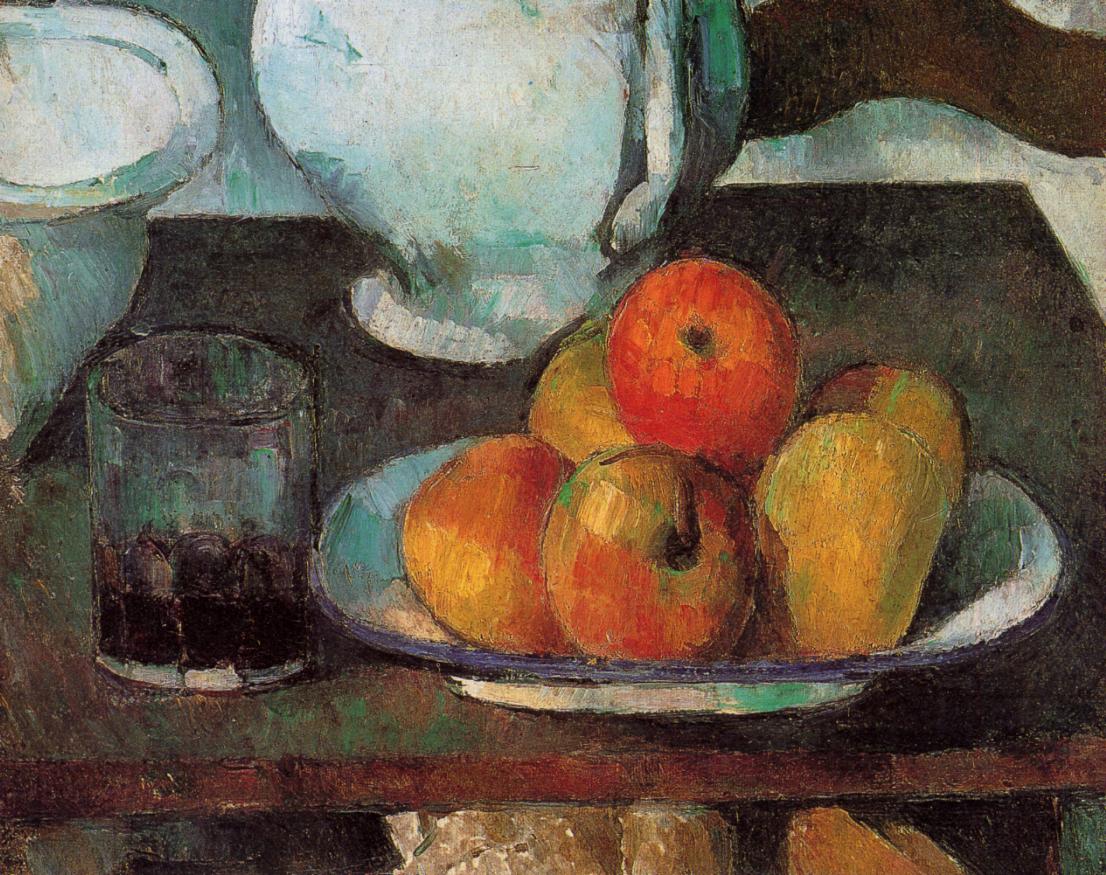

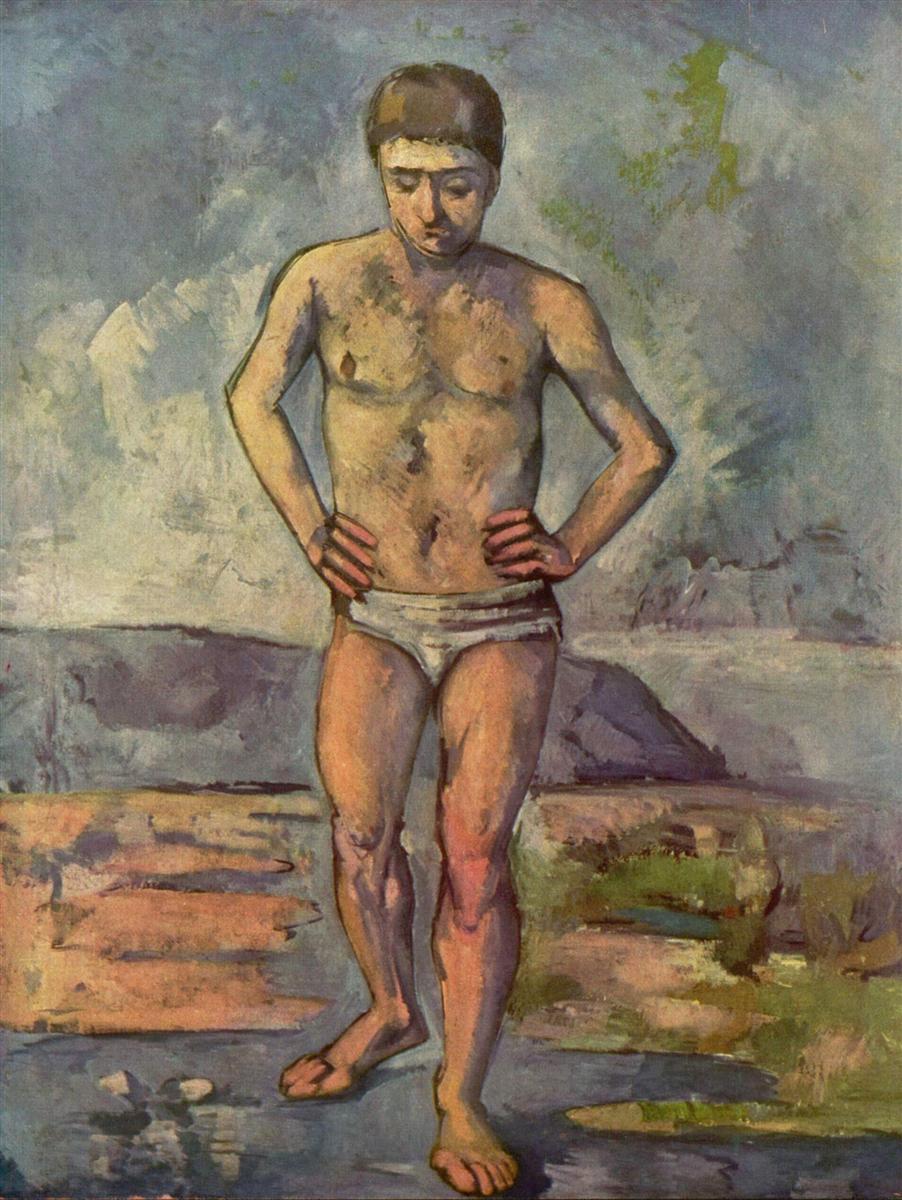

but as for Hokusai and Leonardo, Li Tai Pe and Villion, Verhaeren, Rodin, Cézanne—of these, not to mention the good Lord, all he will ever learn, even there, is hearsay.

Ah, we compute the years and divide them here and there and stop and begin and hesitate between the two.

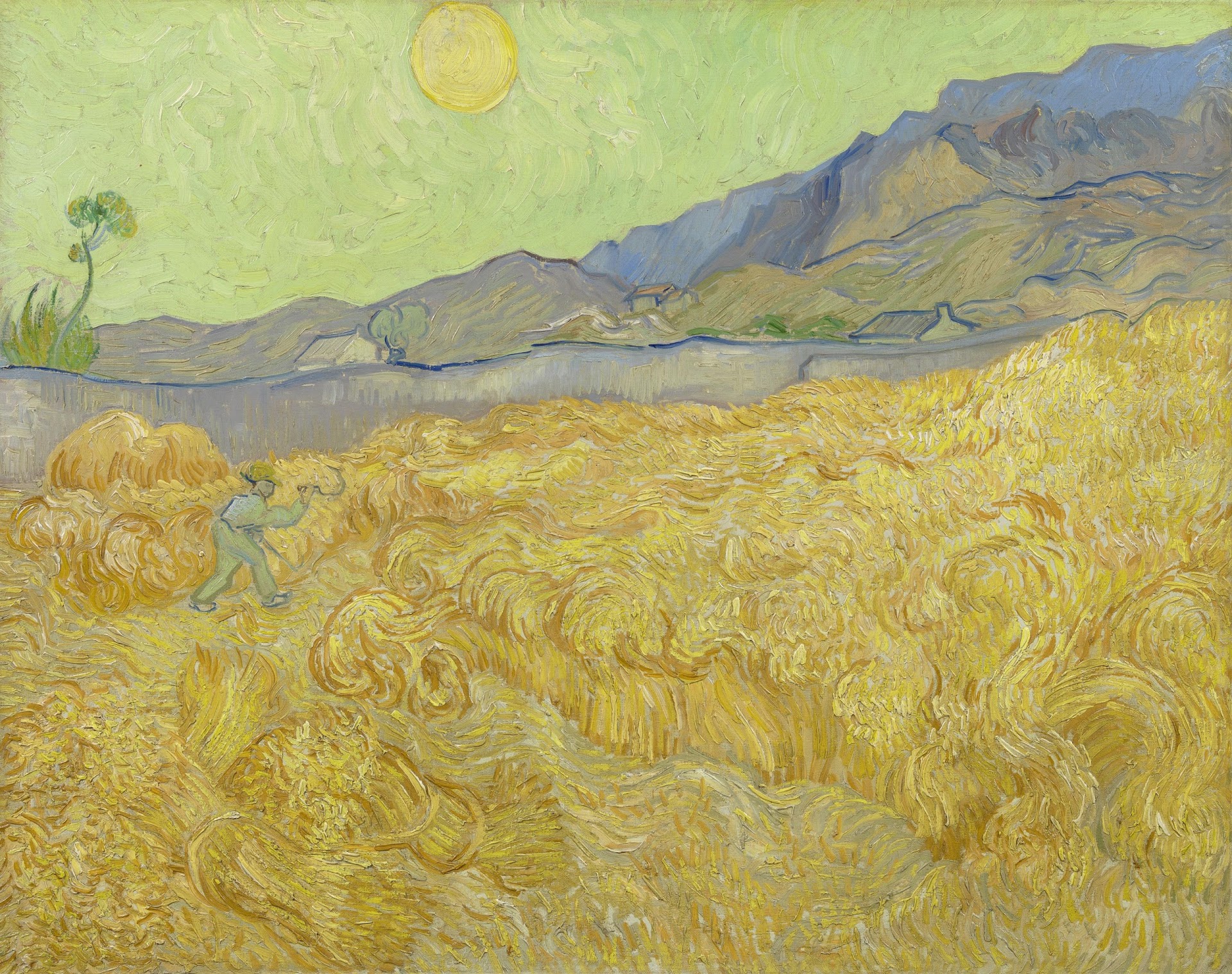

But how very much of one piece is everything we encounter, how related one thing is to the next, how it gave birth to itself and grows up and is educated in its own nature,

and all we basically have to do is to be there, but simply, ardently, the way the earth simply is, consenting to the seasons, light and dark and altogether in space, not asking to rest upon anything other than the net of influences and forces in which the stars feel secure.

Some day the time and composure and patience must also be there to let me continue writing the Notebooks of Malte Laurids; I now know much more about him, or rather: the knowledge will be there when it is needed …

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

THE WORK

I read this letter, and see a miracle.

Here and now, in this moment, we are witnessing Rilke becoming what he is, and has always been, and will always be.

The real work begins after enduring…

SEEING PRACTICE: how related one thing is to the next

Rilke writes:

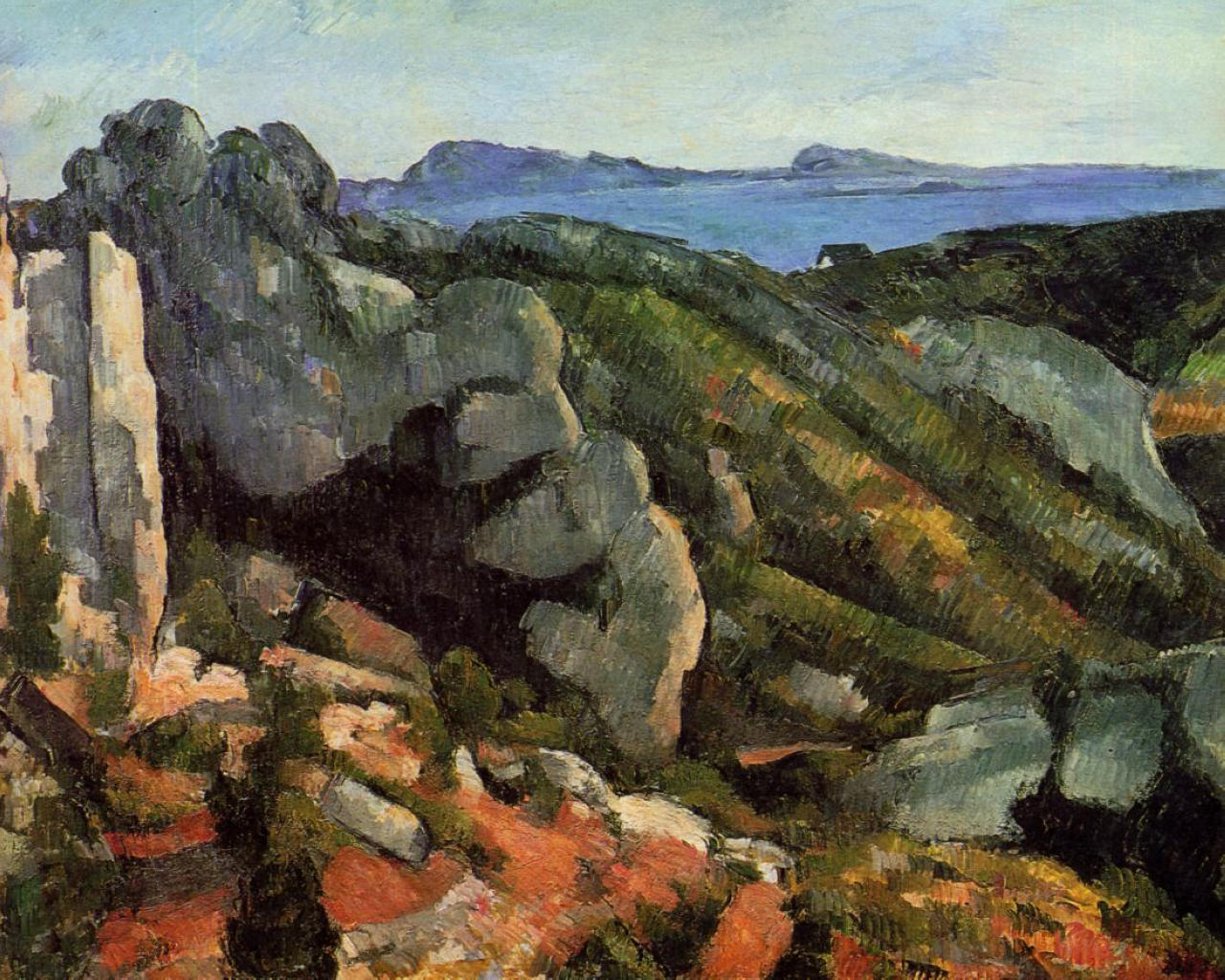

But how very much of one piece is everything we encounter, how related one thing is to the next…

Our brains are trained to see separate objects, not how inseparable they are from what surrounds them. But find a moment or two in your day, and pay attention to how things are related, to the spaces in between, to how very much of one piece is everything. Just rest your awareness in the space BETWEEN objects, not on the objects themselves.