… as always when I fall into the error of writing about art, it was valid more as a personal and provisional insight than as a fact objectively derived from the presence of the pictures.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

Rodin’s drawings were announced as a part of that year’s Salon, but something went wrong. Instead, they were exhibited at Bernheim-Jeune, a Parisian art gallery. So Rilke went there to see them.

He had already seen many of them while working with Rodin on his biography.

OCTOBER 15, 1907 (Part 1)

There indeed were the drawings, many pages which I already knew, which I had helped frame in those cheap white-gold frames that were ordered in such enormous quantities, back then.

Which I knew: but did I really know them?

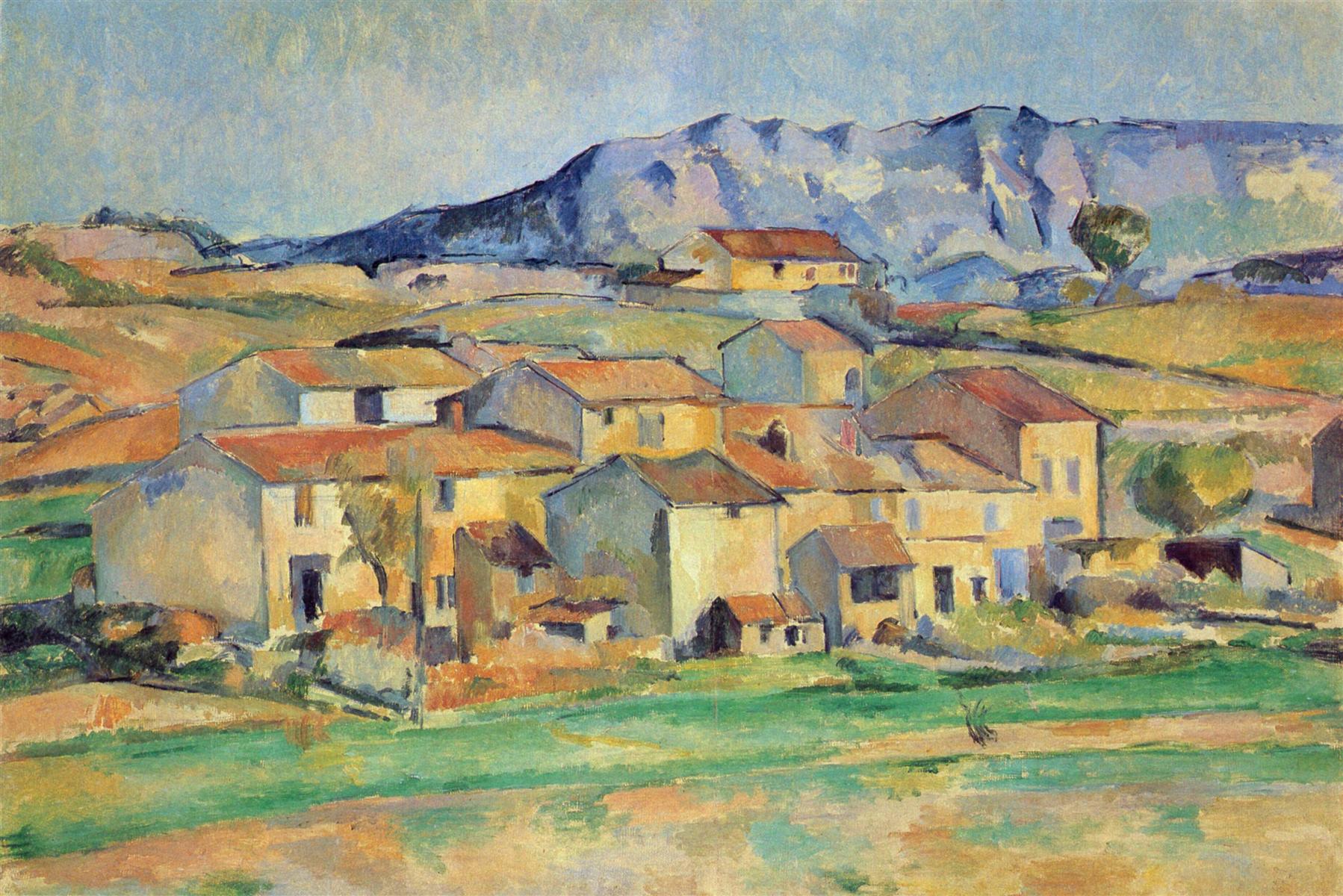

There was so much in them that seemed different to me (is it Cézanne? Is it the passing of time?); what I had written about them two months ago had receded to the limits of validity.

It still was valid, somewhere; but, as always when I fall into the error of writing about art, it was valid more as a personal and provisional insight than as a fact objectively derived from the presence of the pictures.

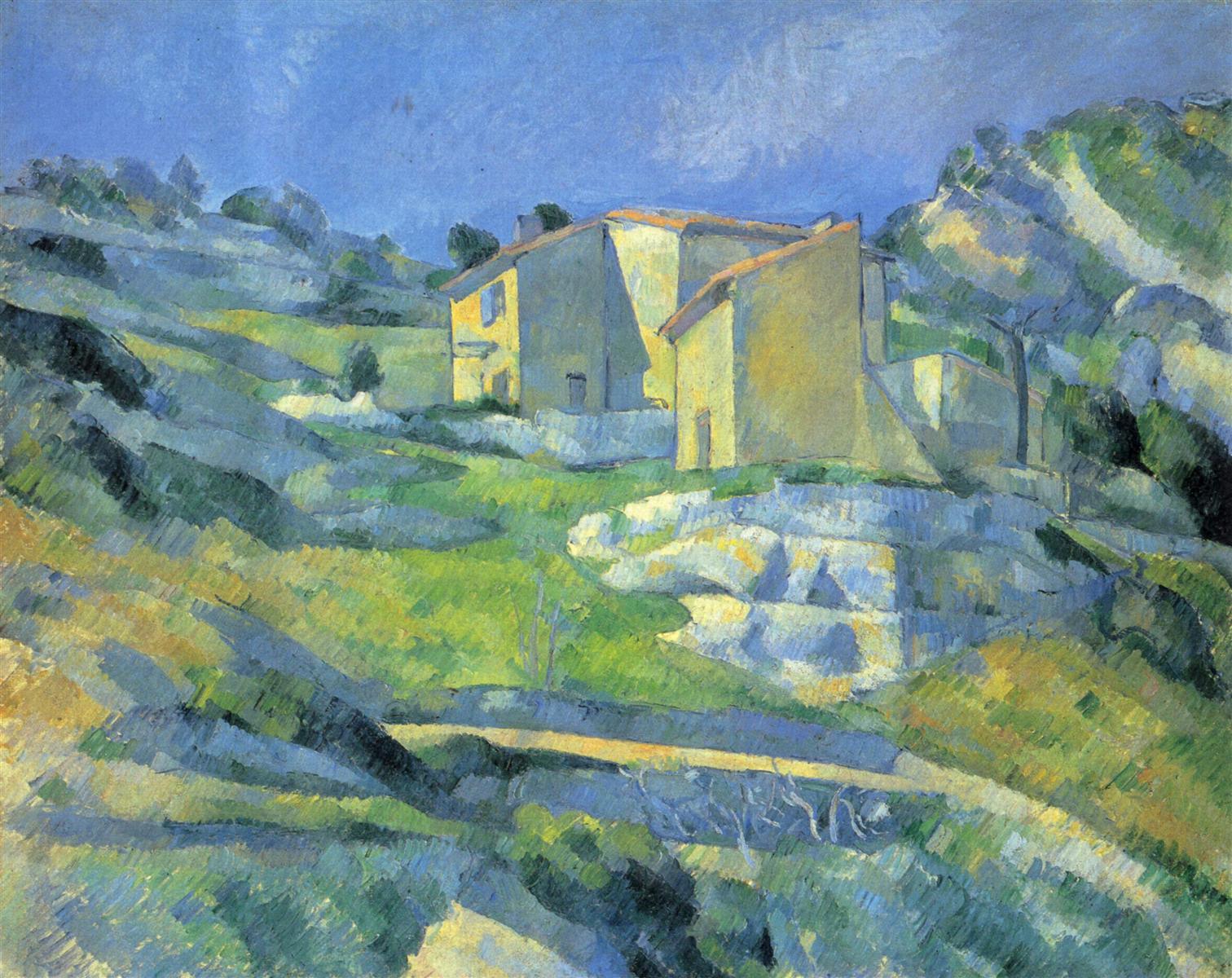

It bothered me that they were so self-explanatory, so easy to interpret; I found myself limited precisely by what ordinarily seemed to open up all sorts of vistas. I would have preferred them like that, without any statement, more discreet, more factual, left alone with themselves.

I admired individual pieces in a new way, and rejected others which seemed to glitter in the reflections of their interpretation; until I reached works which I had not known.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

SUBJECTIVE AND OBJECTIVE

The theme of “subjective and objective” in art is present in the letters in two guises, from two (apparently different) vantage points:

From the point of view of an artist: do I express (subjective) feelings, or (objective) facts, THINGS, reality?

And as a spectator, or a reader: do I connect with a work of art because it touches me personally, subjectively? Or dare I look beyond that, into the reality of its objective presence?

But if a poet writes about art, these vantage points are merged together.

SEEING PRACTICE: OBJECTIVE PRESENCE

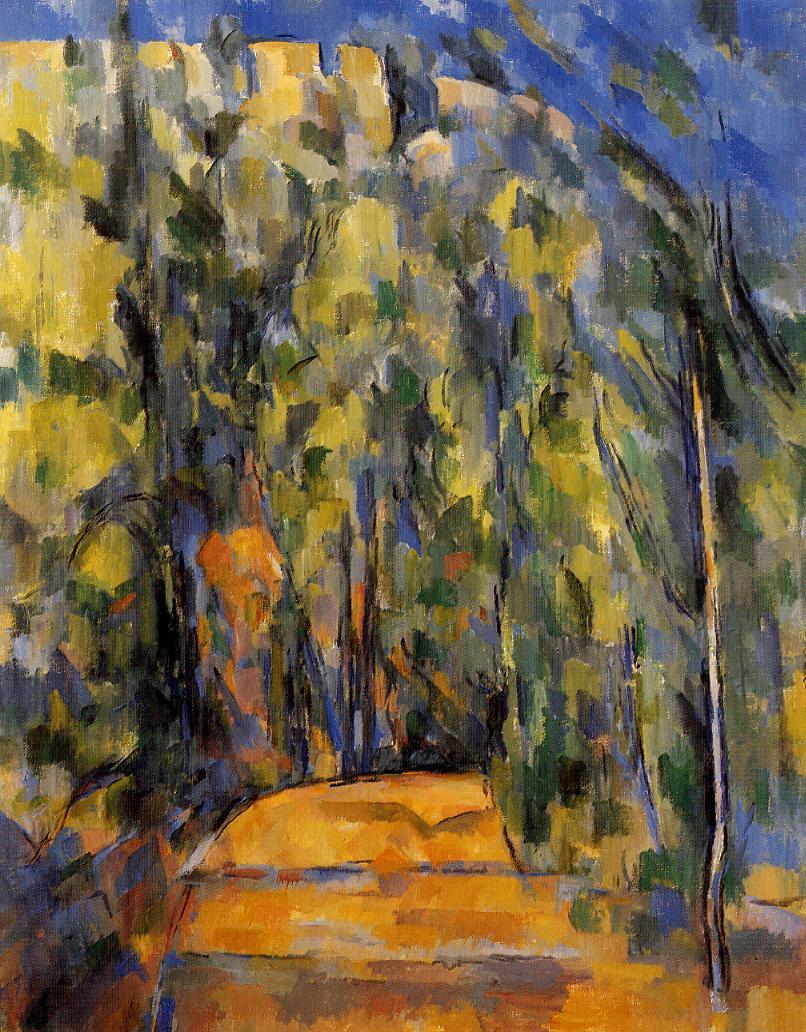

We are often attracted to works of art that have some personal emotional significance for us; that resonate with something in our own interior, on a deeply personal, subjective level. Is this the only way to really CONNECT with a painting, or a song, or a poem?

What Rilke, I think, dances around and approaches from different angles is that a work of art tells (or shows) us a glimpse of objective reality, beyond and above any personal significance we might project onto it.

It is interesting to think about one’s favorite painting(s) in this way: not in terms of one’s own emotional response to them, but as a pathway to a richer reality.