This lying-down-with-the-leper and sharing all one’s own warmth with him, including the heart-warmth of nights of love: this must at some time have been part of an artist’s existence, as a self-overcoming on the way to his new bliss.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

OCTOBER 19, 1907 (Part 1)

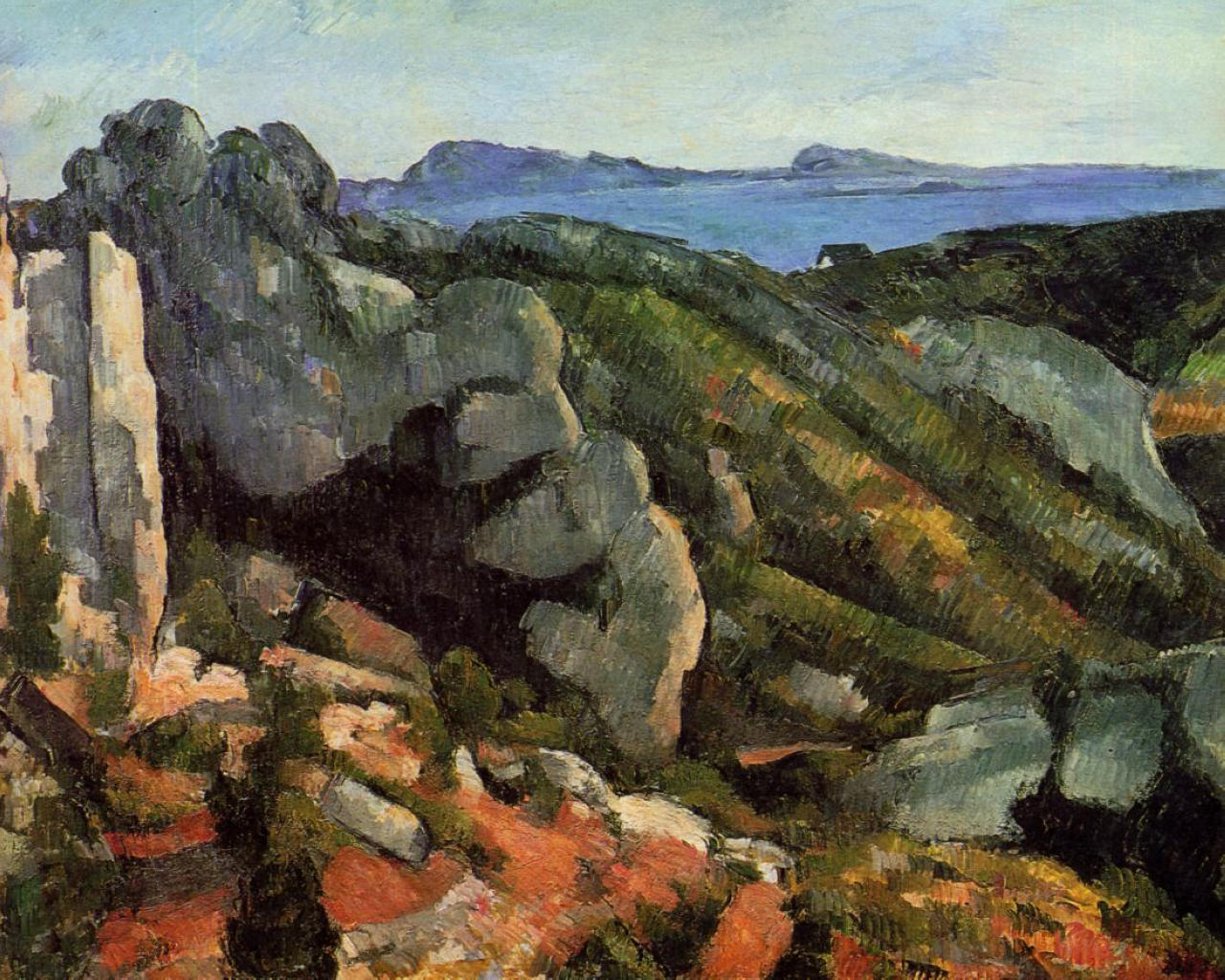

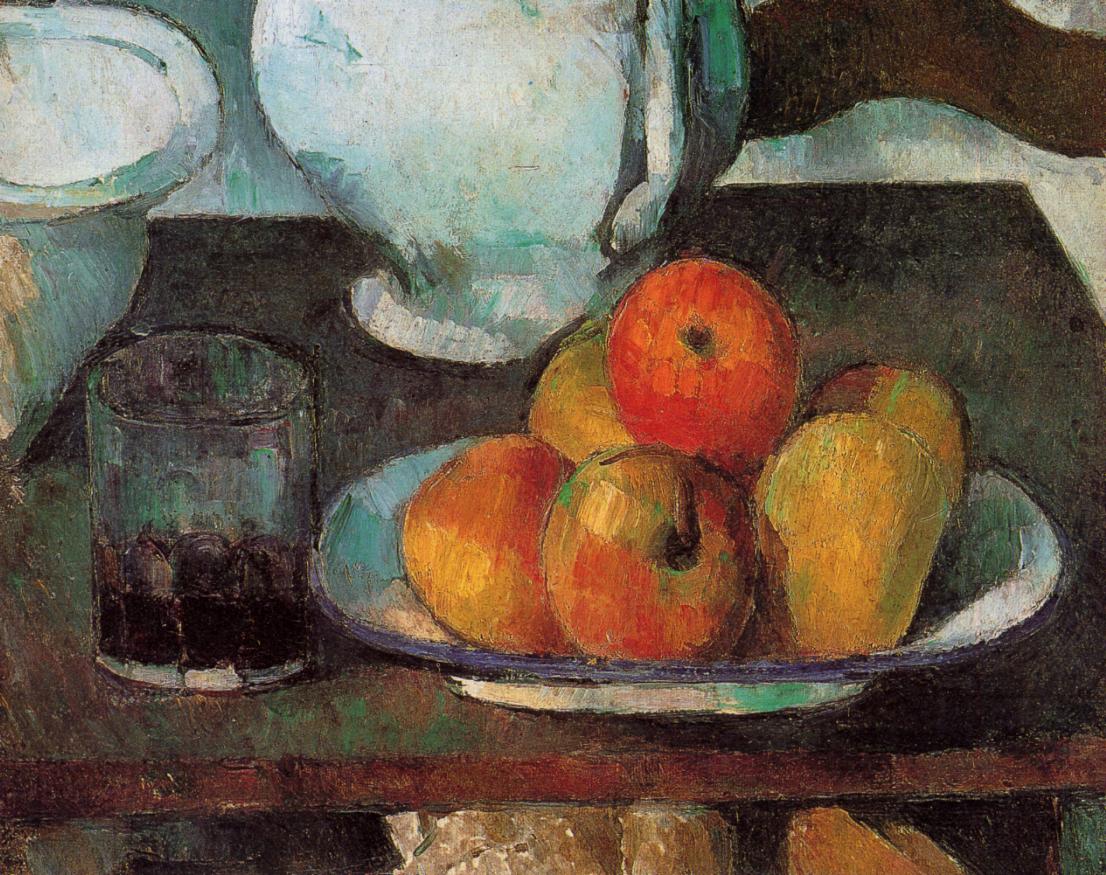

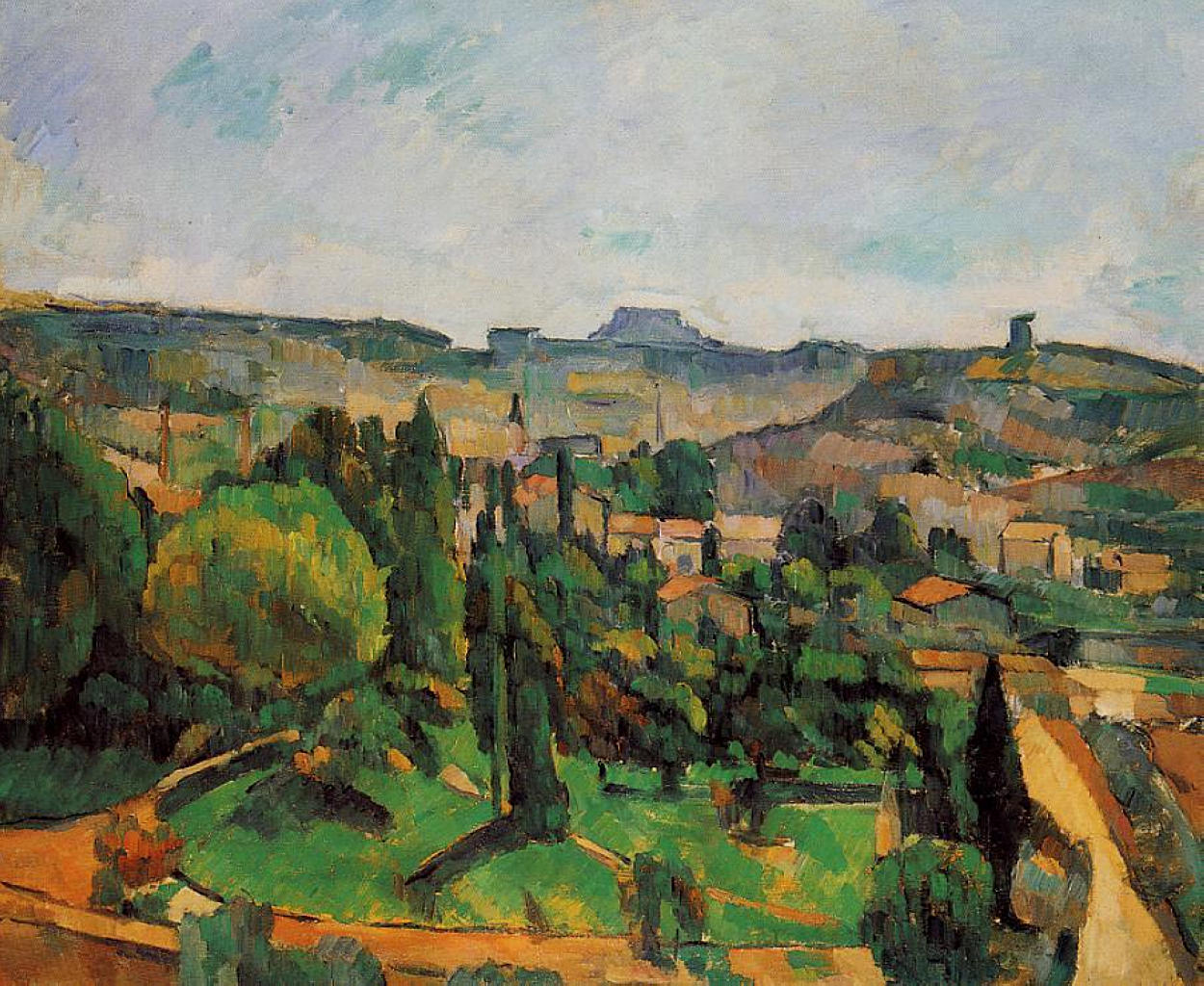

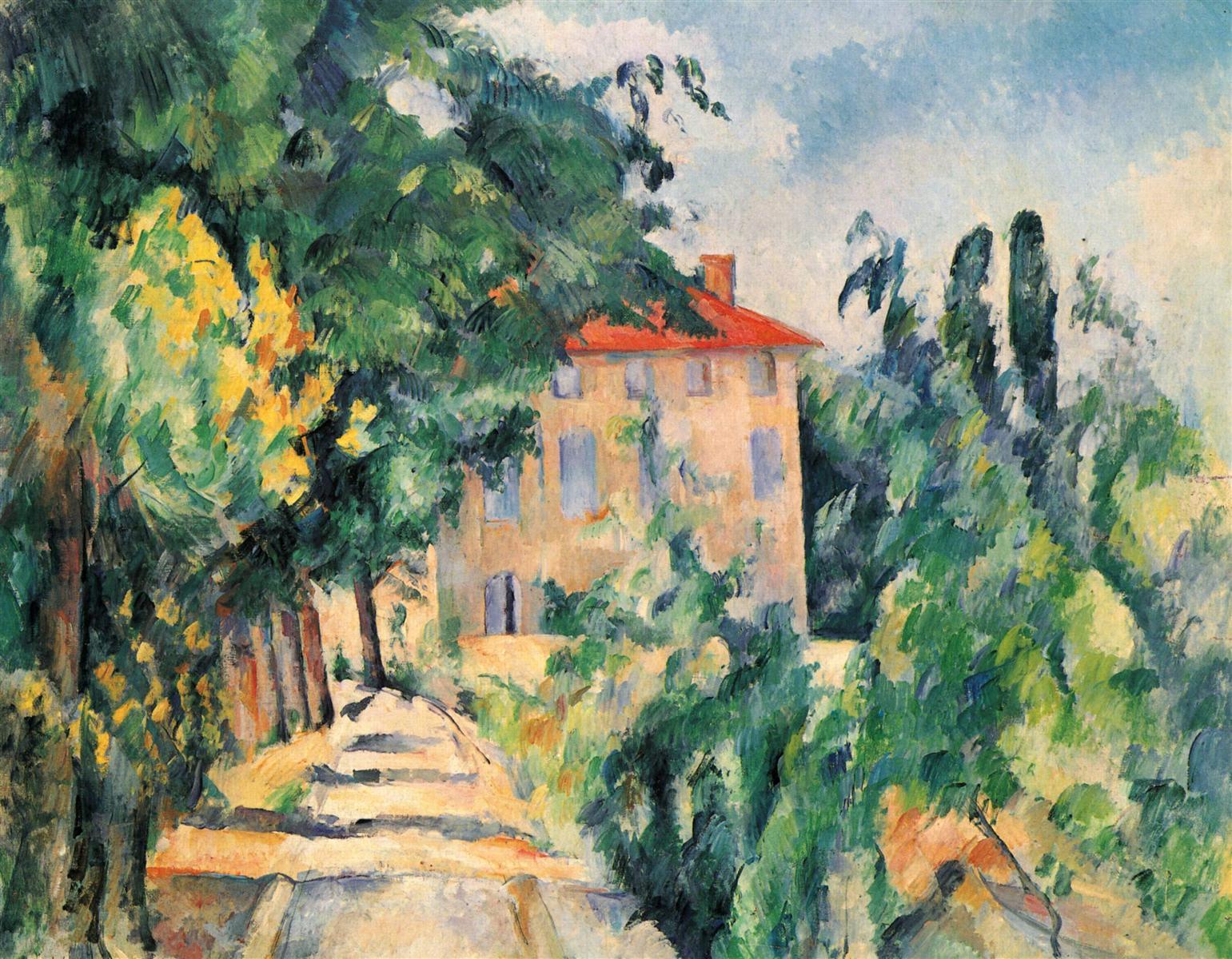

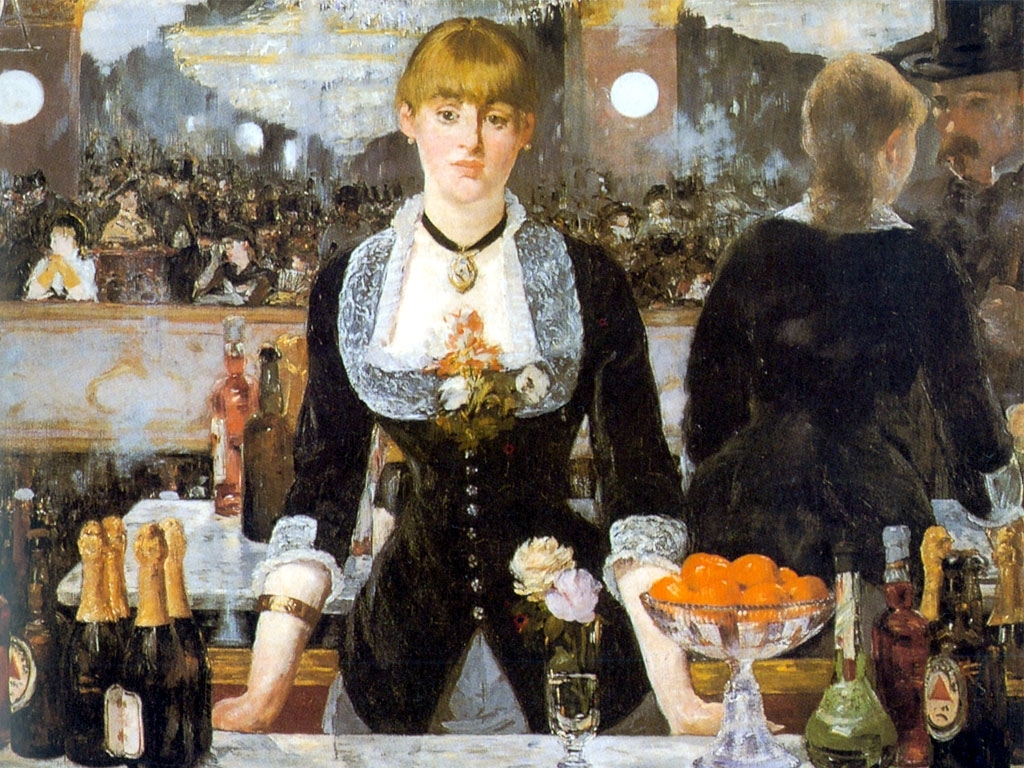

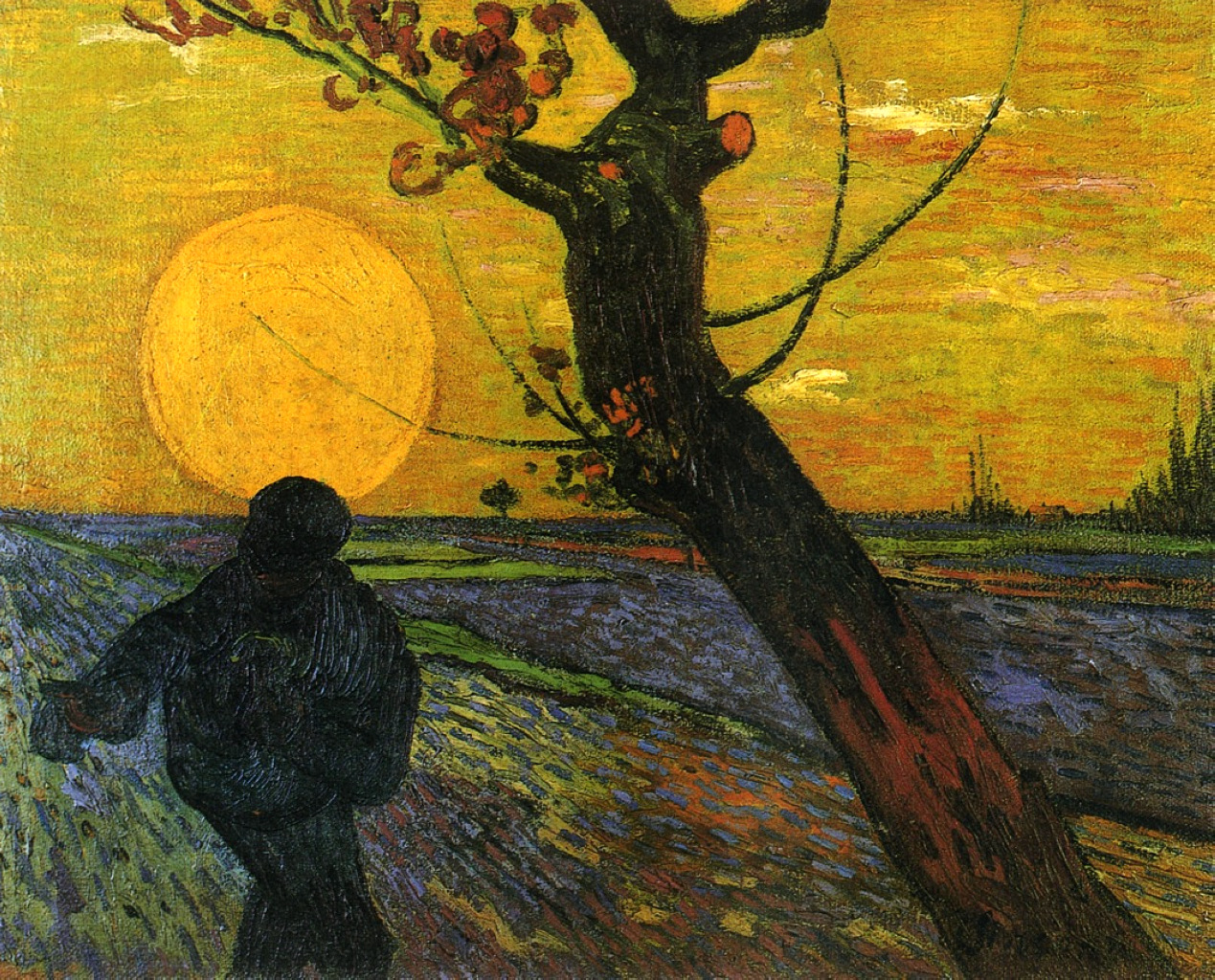

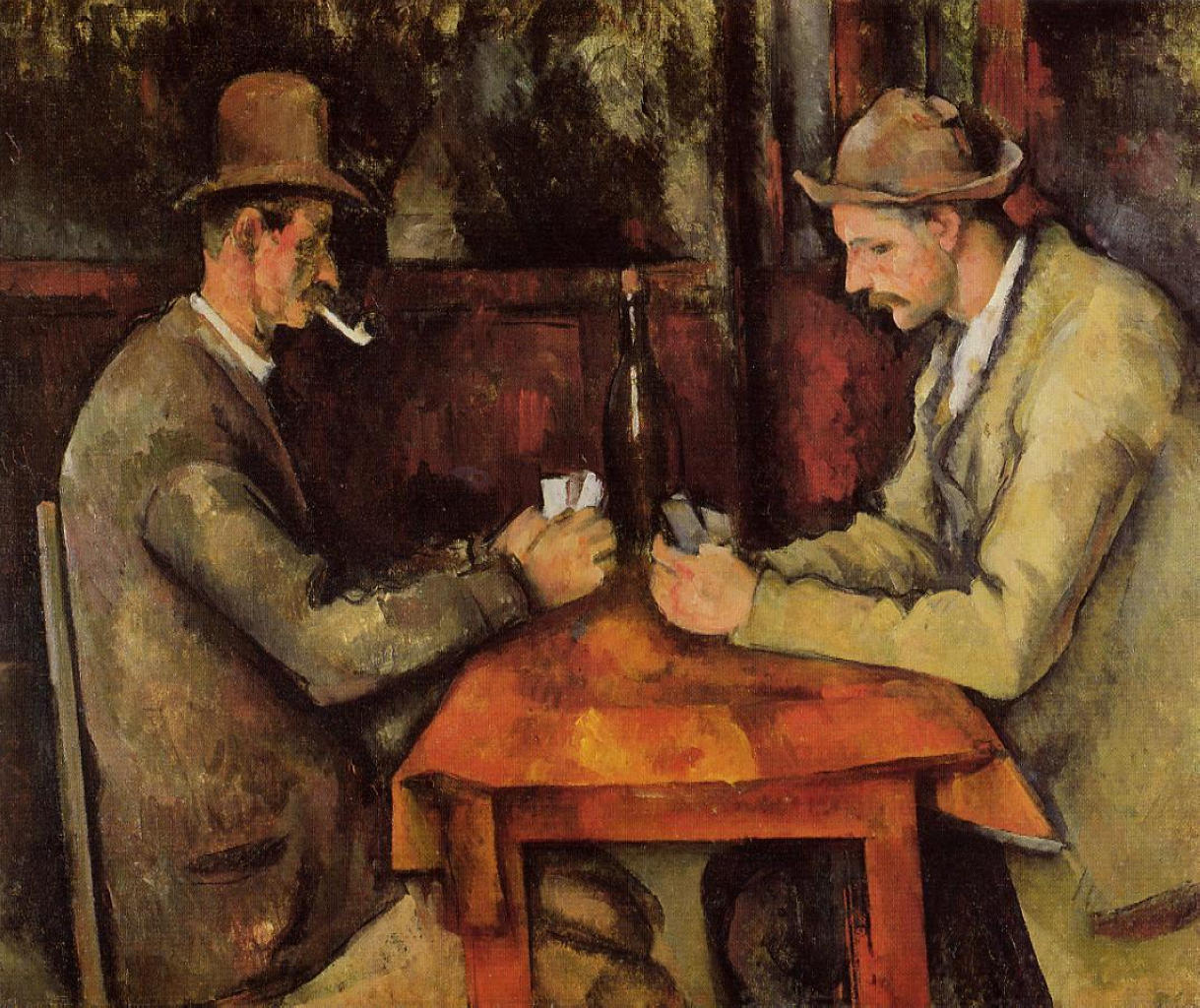

I’m sure you remember … in The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, the place that deals with Baudelaire and his poem: “Carrion.” I couldn’t help thinking that without this poem, the whole trend toward plainspoken truth which we now seem to recognize in Cézanne could not have started; first it had to be there in all its inexorability.

First, artistic perception had to surpass itself to the point of realizing that even something horrible, something that seems no more than disgusting, is, and is valid, along with everything else that is.

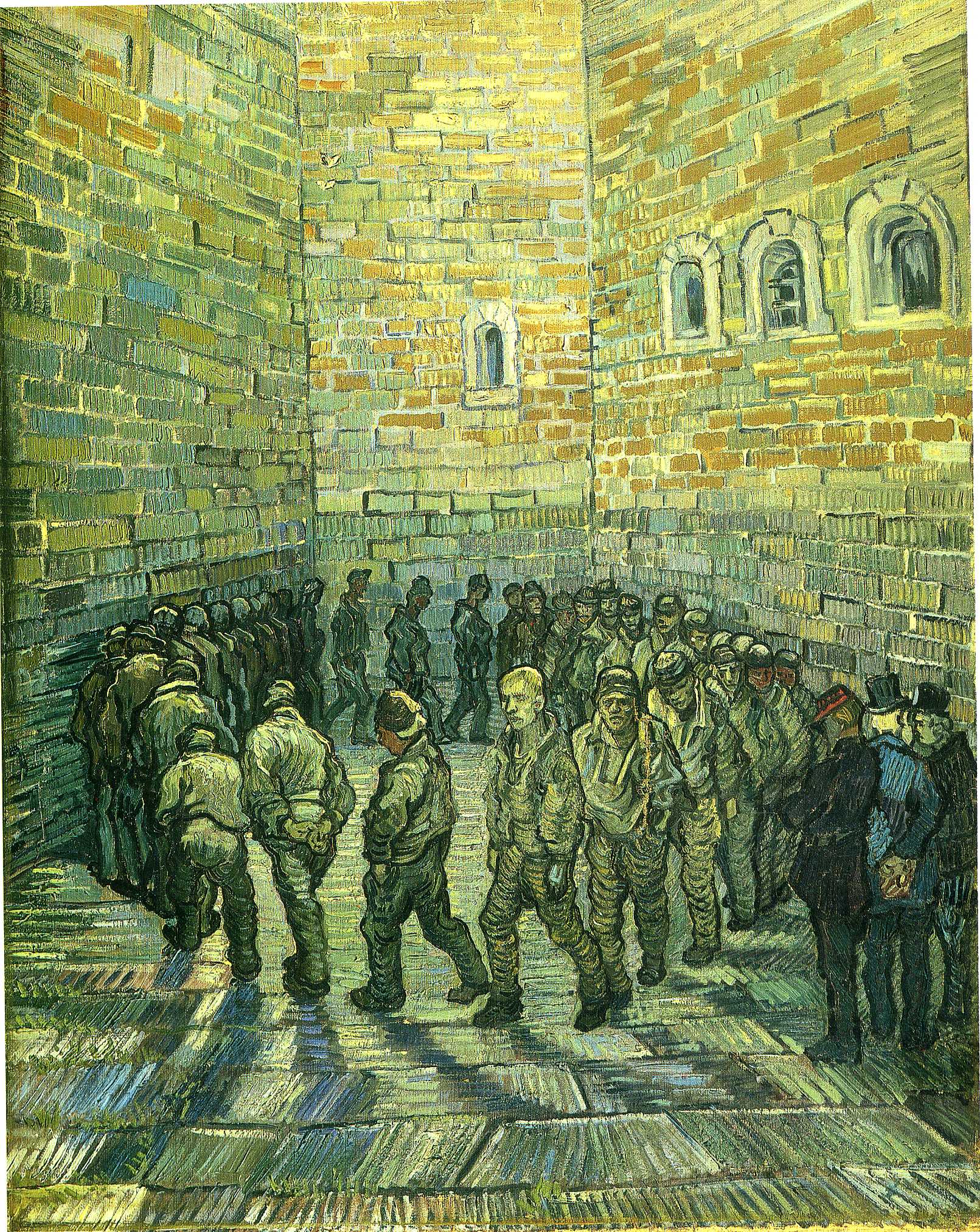

Just as the creative artist is not allowed to choose, neither is he permitted to turn his back on anything that exists: a single refusal at any time, and he is cast out of the state of grace and becomes sinful all the way through.

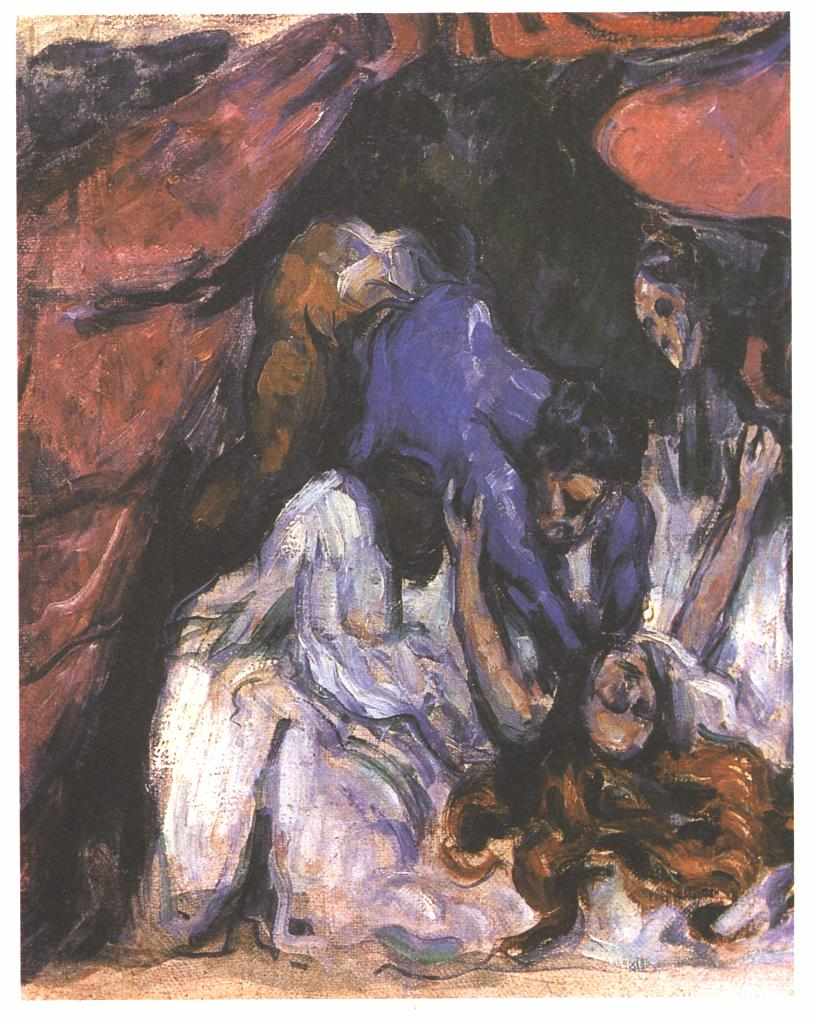

Flaubert, in retelling the legend of Saint-Julien-l’hospitalier with so much discretion and care, showed me this simple believability in the midst of the miraculous, because the artist in him participated in the saint’s decisions, and gave them his happy consent and applause.

This lying-down-with-the-leper and sharing all one’s own warmth with him, including the heart-warmth of nights of love: this must at some time have been part of an artist’s existence, as a self-overcoming on the way to his new bliss.

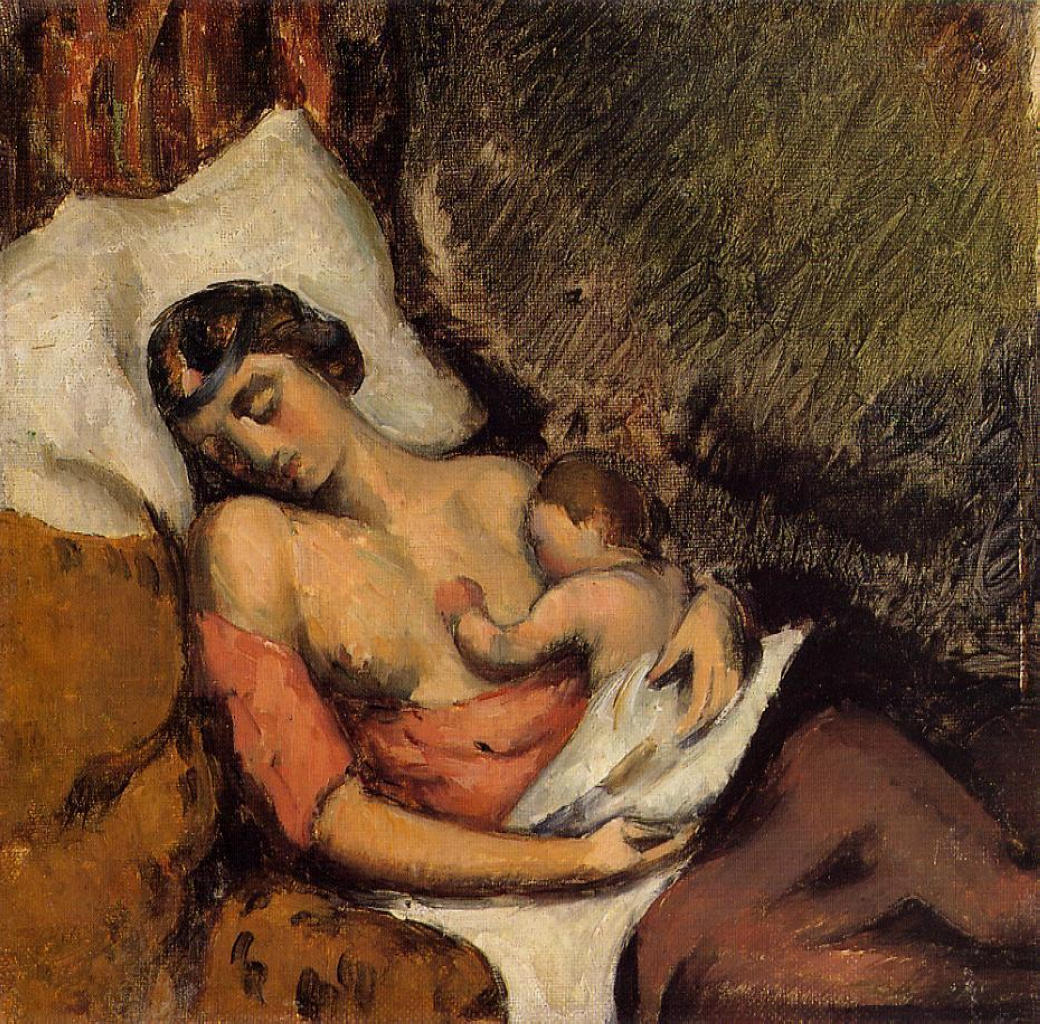

You can imagine how it moves me to read that even in his last years, Cézanne had memorized this very poem—Baudelaire’s Charogne—and recited it word for word. Surely one could find examples among his earlier works where he mightily surpassed himself to achieve the utmost capacity for love.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

STORYLINE: Limitless objectivity

Rilke writes:

Just as the creative artist is not allowed to choose, neither is he permitted to turn his back on anything that exists: a single refusal at any time, and he is cast out of the state of grace and becomes sinful all the way through.

But is this only about artists, or about every single one of us?

I think we have reached the point in evolution where neither of us is permitted to turn their back on anything that exists. Otherwise, we are all doomed.

Artists were just in the vanguard (haven’t they always been in the vanguard of humanity’s evolution?)

SEEING PRACTICE: LOOKING AT UGLINESS

Is it as simple, and as difficult, as this: to see the sheer beauty of the world, one must learn not to turn back on its ugliness?

In “The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge”, Rilke writes:

Do you remember Baudelaire’s incredible poem “Une Charogne”? Perhaps I understand it now. Except for the last stanza, he was in the right. What should he have done after that happened to him? It was his task to see, in this terrifying and apparently repulsive object, the Being that underlies all individual beings. There is no choice, no refusal. Do you think it was by chance that Flaubert wrote his “Saint Julien l’Hospitalier”? This, it seems to me, is the test: whether you can bring yourself to lie beside a leper and warm him with the warmth of your own heart—such an action could only have good results. (Translated by Stephen Mitchell, Vintage International Edition (1990)).

Charles Baudelaire. The Carcase

The object that we saw, let us recall,

This summer morn when warmth and beauty mingle —

At the path’s turn, a carcase lay asprawl

Upon a bed of shingle.

Legs raised, like some old whore far-gone in passion,

The burning, deadly, poison-sweating mass

Opened its paunch in careless, cynic fashion,

Ballooned with evil gas.

On this putrescence the sun blazed in gold,

Cooking it to a turn with eager care —

So to repay to Nature, hundredfold,

What she had mingled there.

The sky, as on the opening of a flower,

On this superb obscenity smiled bright.

The stench drove at us, with such fearsome power

You thought you’d swoon outright.

Flies trumpeted upon the rotten belly

Whence larvae poured in legions far and wide,

And flowed, like molten and liquescent jelly,

Down living rags of hide.

The mass ran down, or, like a wave elated

Rolled itself on, and crackled as if frying:

You’d think that corpse, by vague breath animated,

Drew life from multiplying.

Through that strange world a rustling rumour ran

Like rushing water or a gust of air,

Or grain that winnowers, with rhythmic fan,

Sweep simmering here and there.

It seemed a dream after the forms grew fainter,

Or like a sketch that slowly seems to dawn

On a forgotten canvas, which the painter

From memory has drawn.

Behind the rocks a restless cur that slunk

Eyed us with fretful greed to recommence

His feast, amidst the bonework, on the chunk

That he had torn from thence.

Yet you’ll resemble this infection too

One day, and stink and sprawl in such a fashion,

Star of my eyes, sun of my nature, you,

My angel and my passion!

Yes, you must come to this, O queen of graces,

At length, when the last sacraments are over,

And you go down to moulder in dark places

Beneath the grass and clover.

Then tell the vermin as it takes its pleasance

And feasts with kisses on that face of yours,

I’ve kept intact in form and godlike essence

Our decomposed amours!

— From Roy Campbell, Poems of Baudelaire (New York: Pantheon Books, 1952). Click for other translations.

Here is a translation of Flaubert’s retelling of The Legend of St. Julian the Hospitaller.