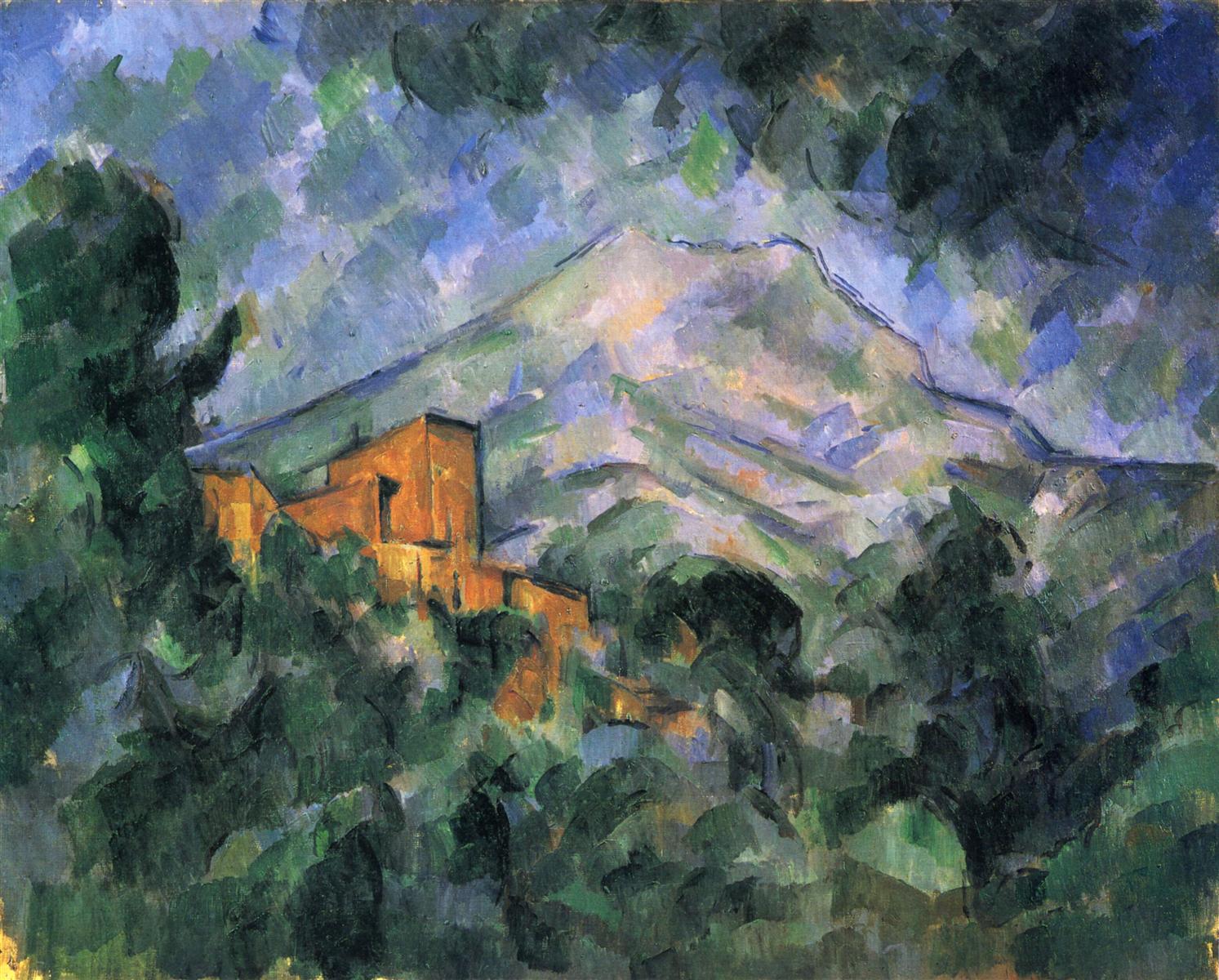

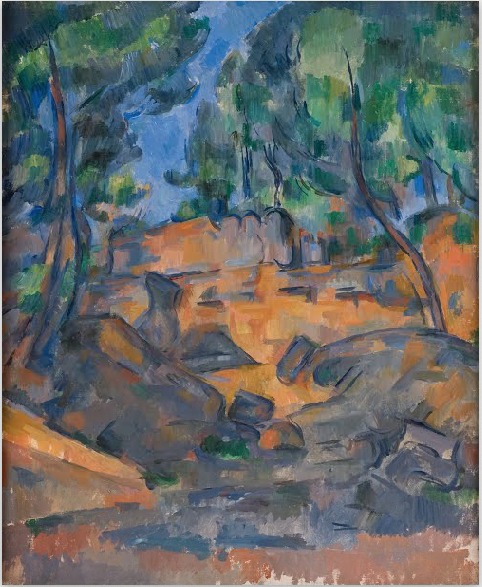

I could imagine someone writing a monograph on the color blue, from the dense waxy blue of the Pompeiian wall paintings to Chardin and further to Cézanne: what a biography!

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

We are still in the Louvre, with Rilke tracing the origins of Cézanne’s color.

OCTOBER 8, 1907 (PART 2)

Contemporaneously with Guardi and Tiepolo, a woman too was painting, a Venetian, who came to all the courts and whose name was among the most well known of her time: Rosalba Carriera.

<…>

Three portraits are in the Louvre. A young lady, her face raised up by the straight neck and then turned naively toward the viewer, and in front of her décolleté lace dress she holds a small clear-eyed capuchin monkey who is peering out from the lower edge of the half-length portrait as eagerly as she’s looking out on top, just a bit more indifferently.

He’s reaching out with one small perfidious black hand to draw her tender, distracted hand into the picture by one slender finger.

This is so full of one period that it is valid for all times. And it is lovely and lightly painted, but really painted. There’s also a blue cloak in the picture and one whole lilac-white gillyflower stem, which, strangely, takes the place of a breast ornament.

And I noticed that this blue is that special eighteenth-century blue that you can find everywhere, in La Tour,

in Peronnet,

(I could imagine someone writing a monograph on the color blue, from the dense waxy blue of the Pompeiian wall paintings to Chardin and further to Cézanne: what a biography!)

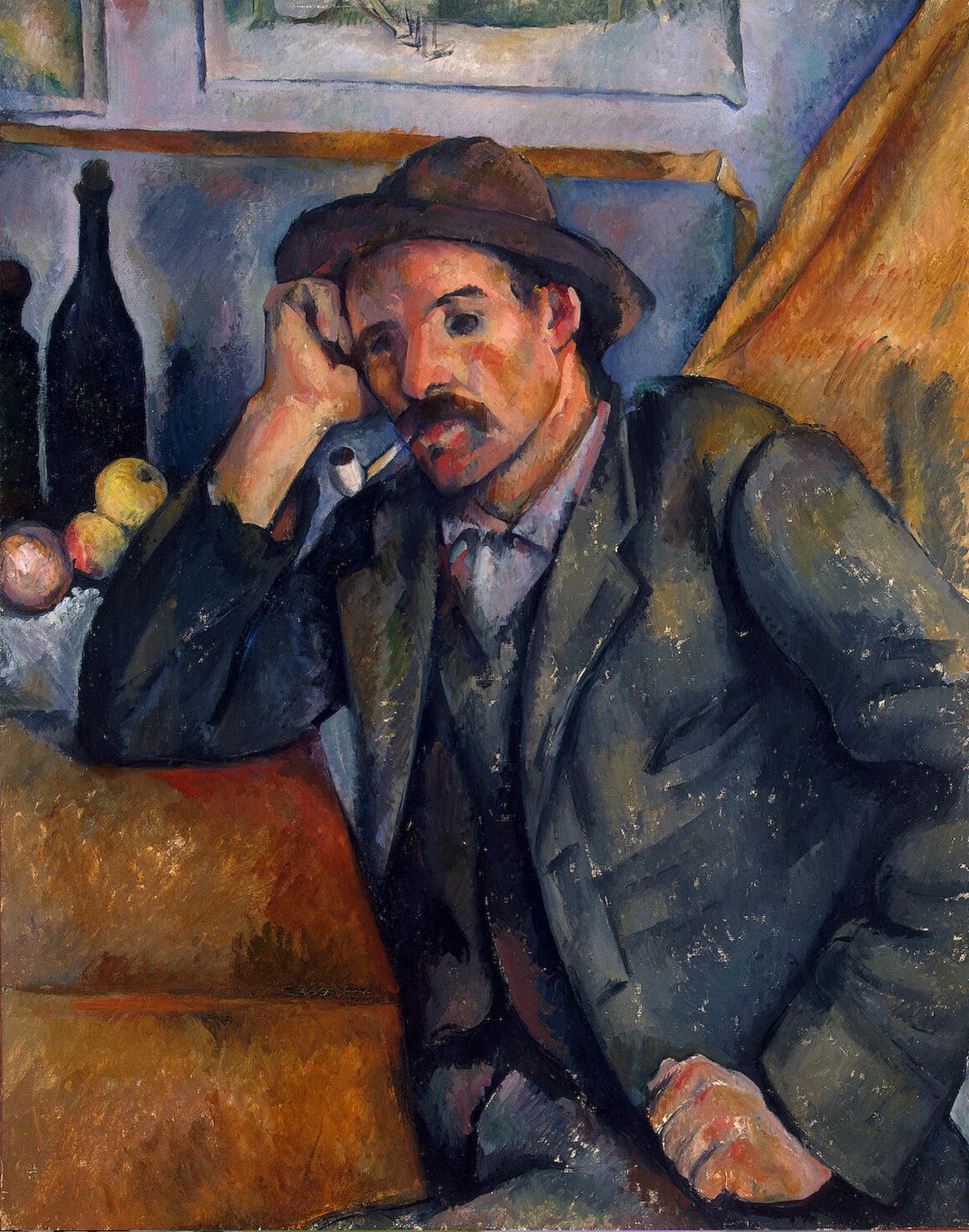

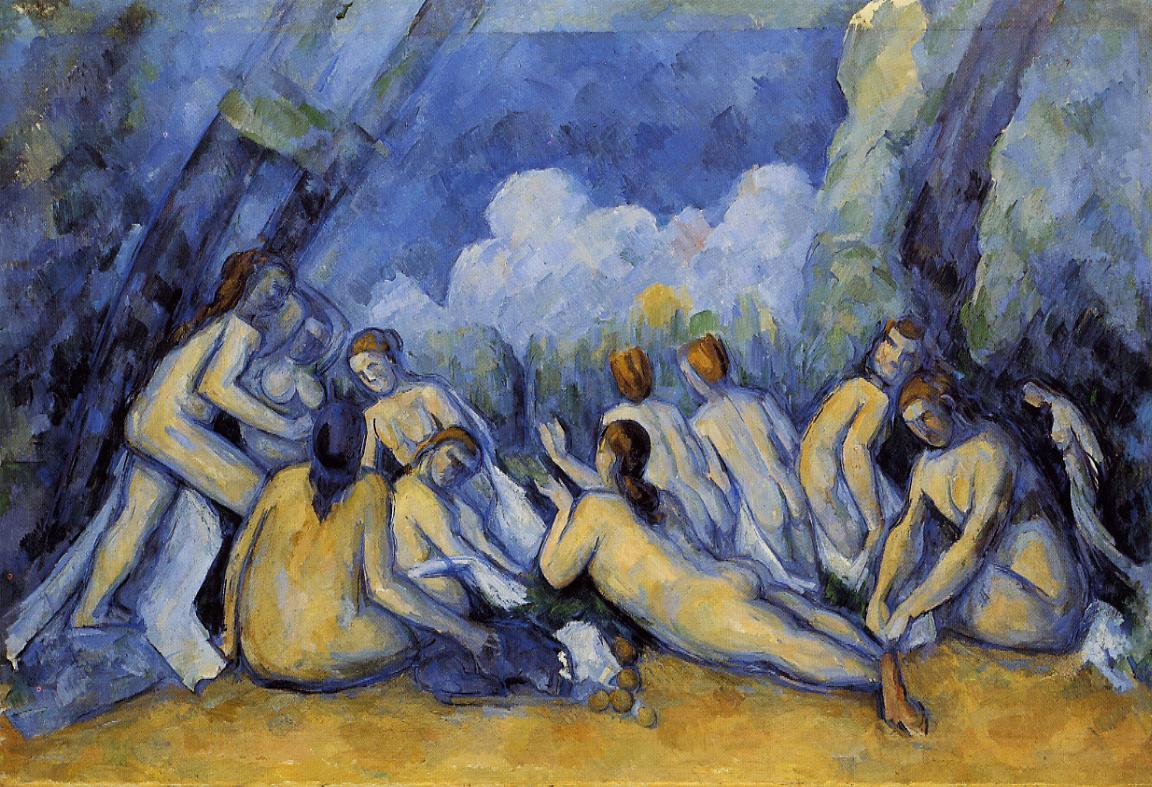

For Cézanne’s very unique blue is descended from these, it comes from the eighteenth-century blue which Chardin stripped of its pretension and which now, in Cézanne, no longer carries any secondary significance.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

MONOGRAPH on THE COLOR BLUE

Heinrich Wiegand Petzet writes in his introduction to “Letters on Cézanne”:

In one of the letters, he speaks of the possibility of writing a monograph on the color blue, beginning with the pastels of Rosalba Carriera and the special blue of the eighteenth century, whereupon he mentions Cézanne’s “very unique blue.” In the course of the letters he produces a series of variations of this blue, formulations whose expressive power exceeds everything that has ever been said about this color.

Here are some of these formulations:

- completely supportless blue

- cold, too remotely blissful barely-blue

- blue dove-gray

- an ancient Egyptian shadow-blue

- self-contained blue

- listening blue

- thunderstorm blue

- bourgeois cotton blue

- densely quilted blue, and finally:

- full of revolt Blue, Blue, Blue.

He is writing this monograph on the color blue, in these very letters.

Isn’t it strange how one’s best work sometimes happens not as “work”, but just so, as the unfolding of life, without pretension?

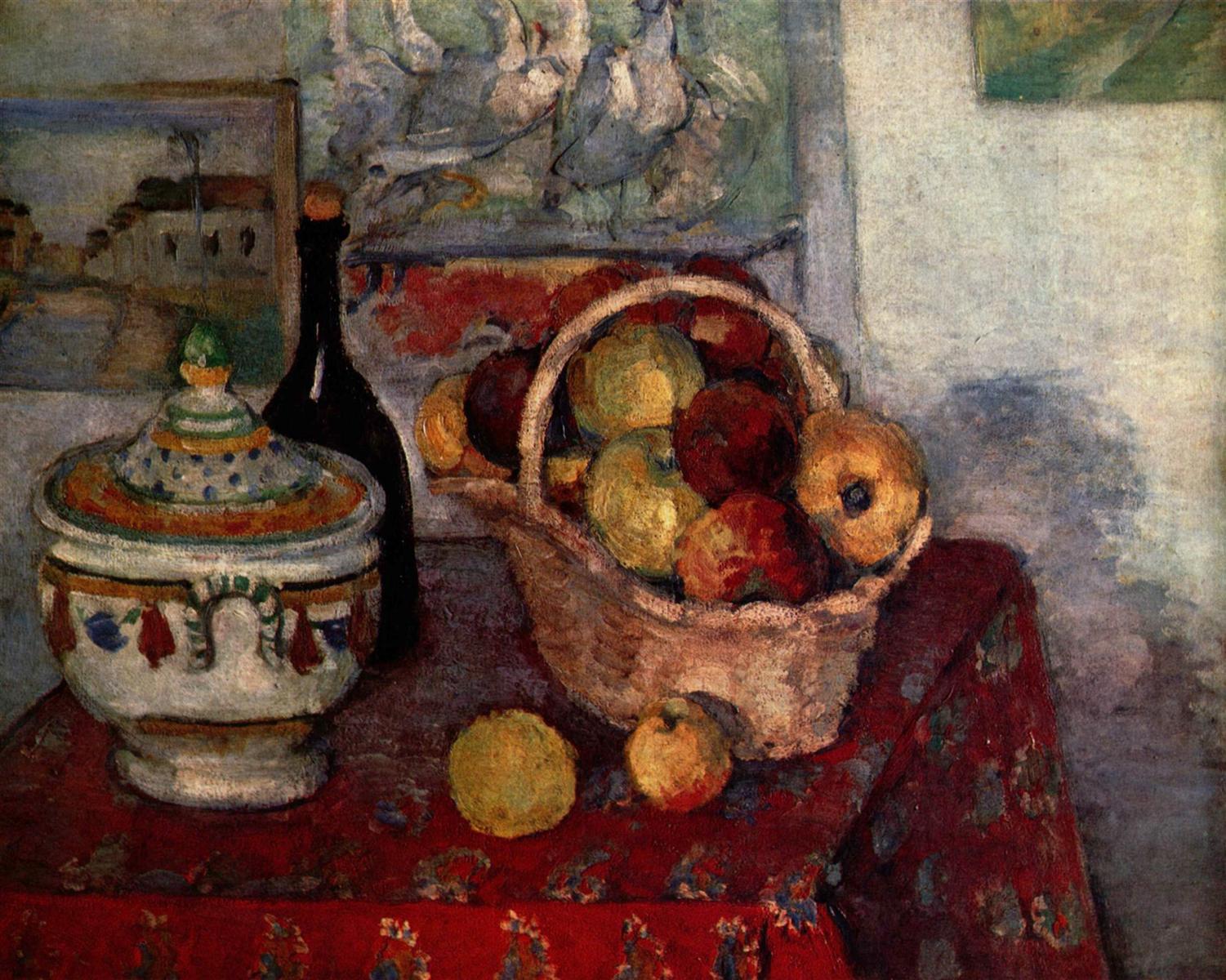

Gradually stripping everything of pretension: the color blue, the apples, the work: this is the deepest motive of these letters. For Rilke, this is also the quintessence of the evolution of art, be it poetry or painting.

SEEING PRACTICE: THE COLOR BLUE

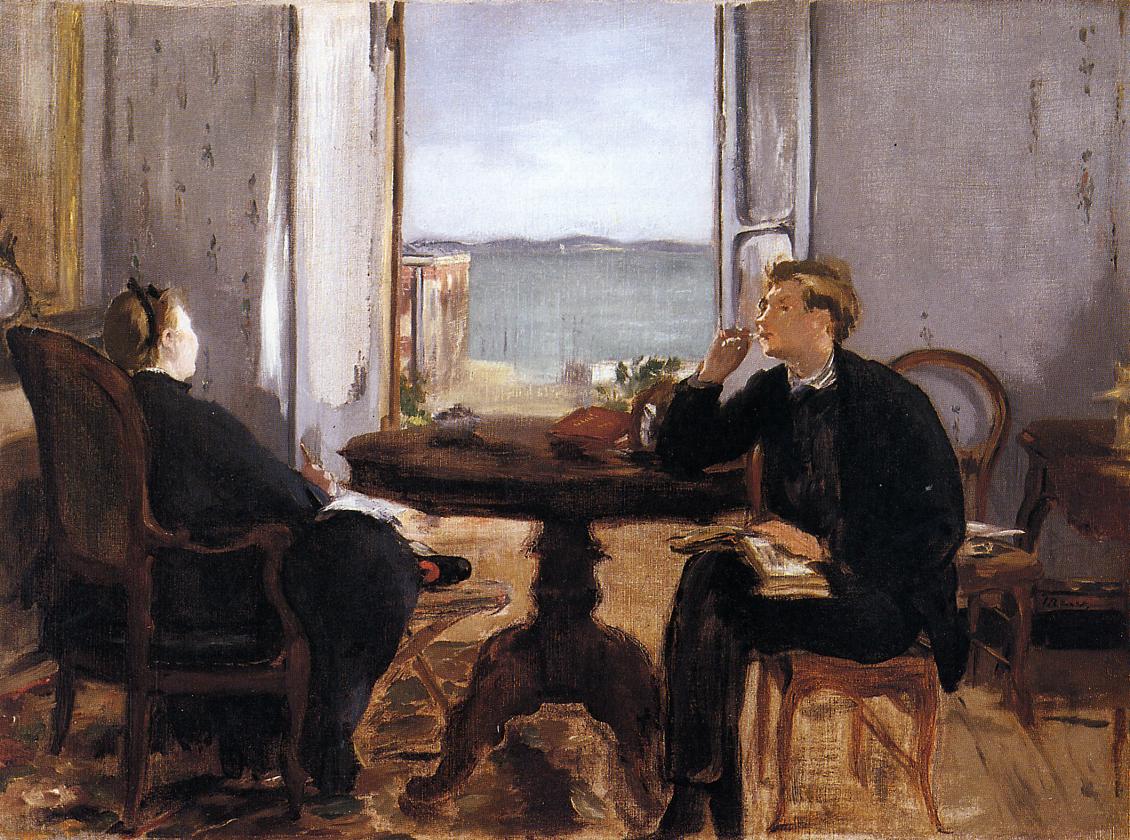

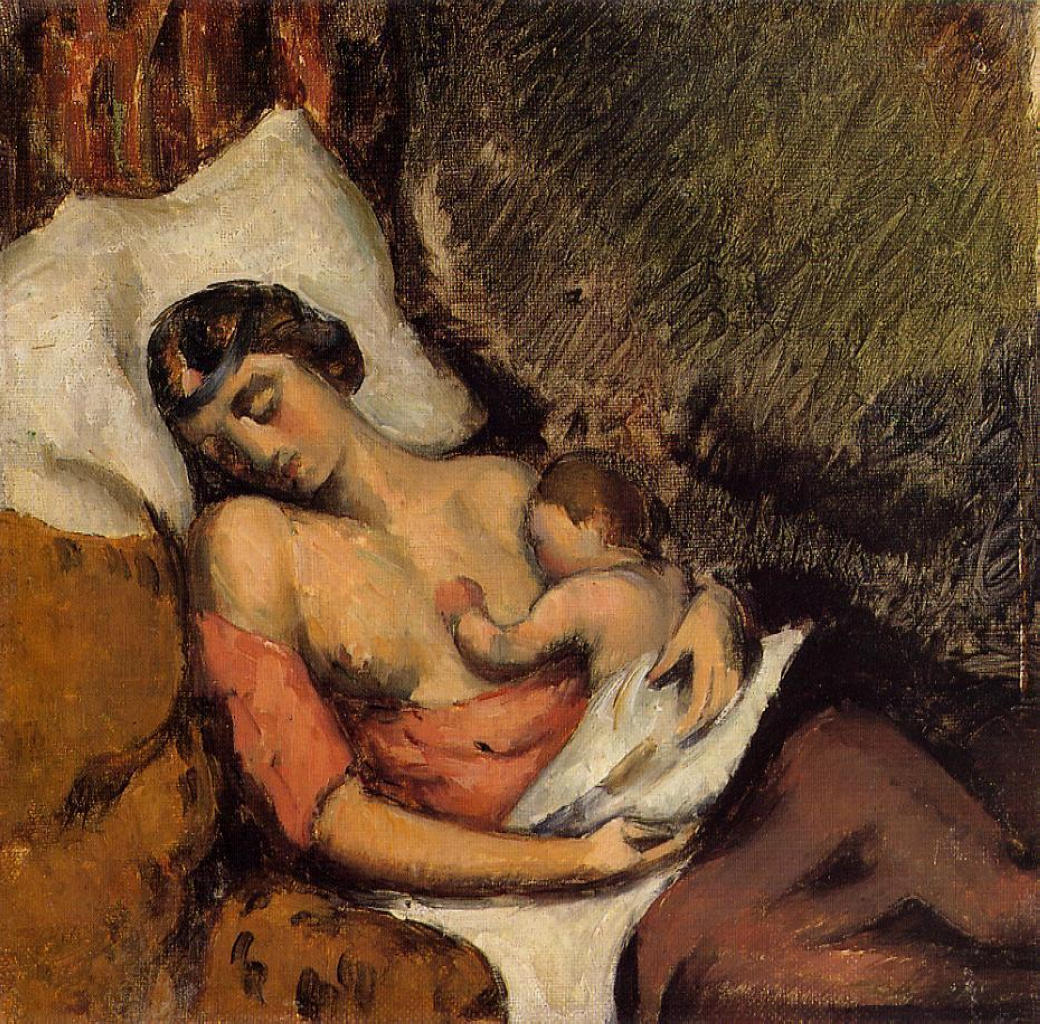

A lot of color nuances disappear in reproductions, but it is still possible to get a glimpse of the evolution of blue Rilke writes about.

But is it just the evolution of painting, or the evolution of our sense of vision?

Or of the color blue itself?

After all, color as we know it doesn’t exist without vision; it is a product of the brain.

The magic of painting is in its ability to create a space where the brain shakes off some of its habituated routines, and is able to perceive color differently, more richly, more intensely than in “real life”. And some of this can then spill over into our “normal” vision — that’s how art expands and cleanses our visual perception.

As you go through your day, notice the color blue as you see it in nature. Has you perception shifted in response to the paintings you have just seen?