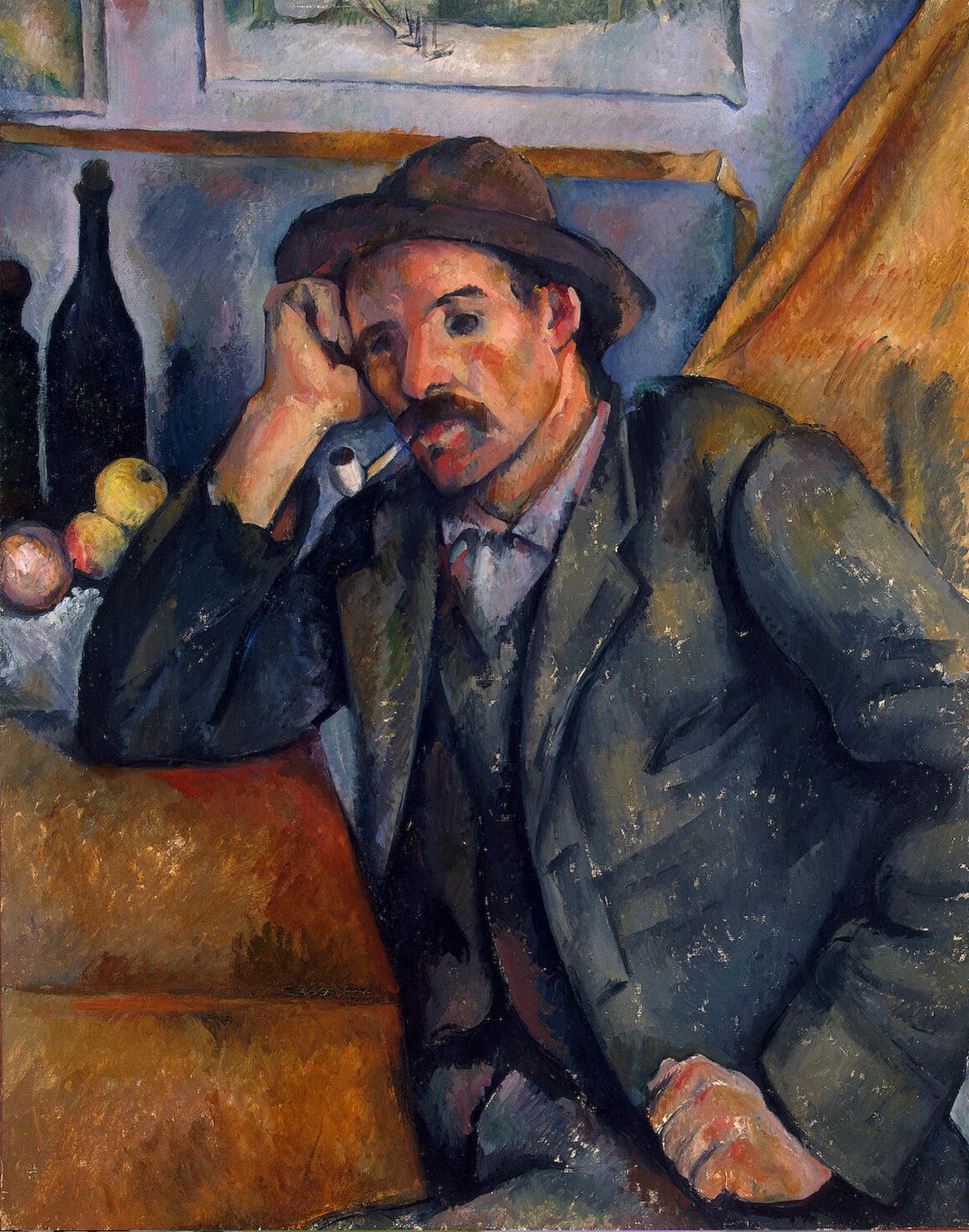

He (Cézanne) sat there in front of it like a dog, just looking, without any nervousness, without any ulterior motive

Mathilde Vollmoeller to Rainer Maria Rilke

OCTOBER 12, 1907 (Part 2)

I recently asked Mathilde Vollmoeller to go through the Salon with me sometime, so that I could see my impression in the presence of someone whom I believe to be calm and not distracted by literature. Yesterday we went there together.

Cézanne prevented us from getting to anything else. I notice more and more what an event this is. But imagine my surprise when Miss V., with her painterly training and eye, said:

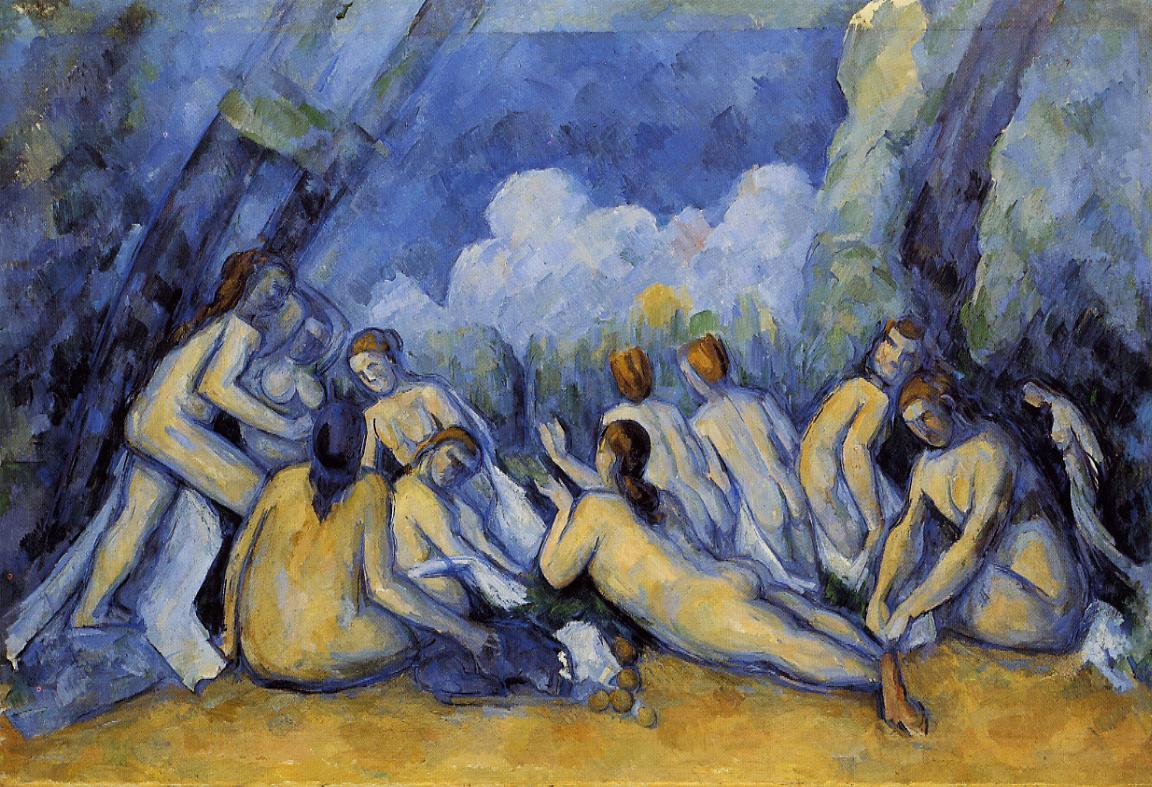

He sat there in front of it like a dog, just looking, without any nervousness, without any ulterior motive.

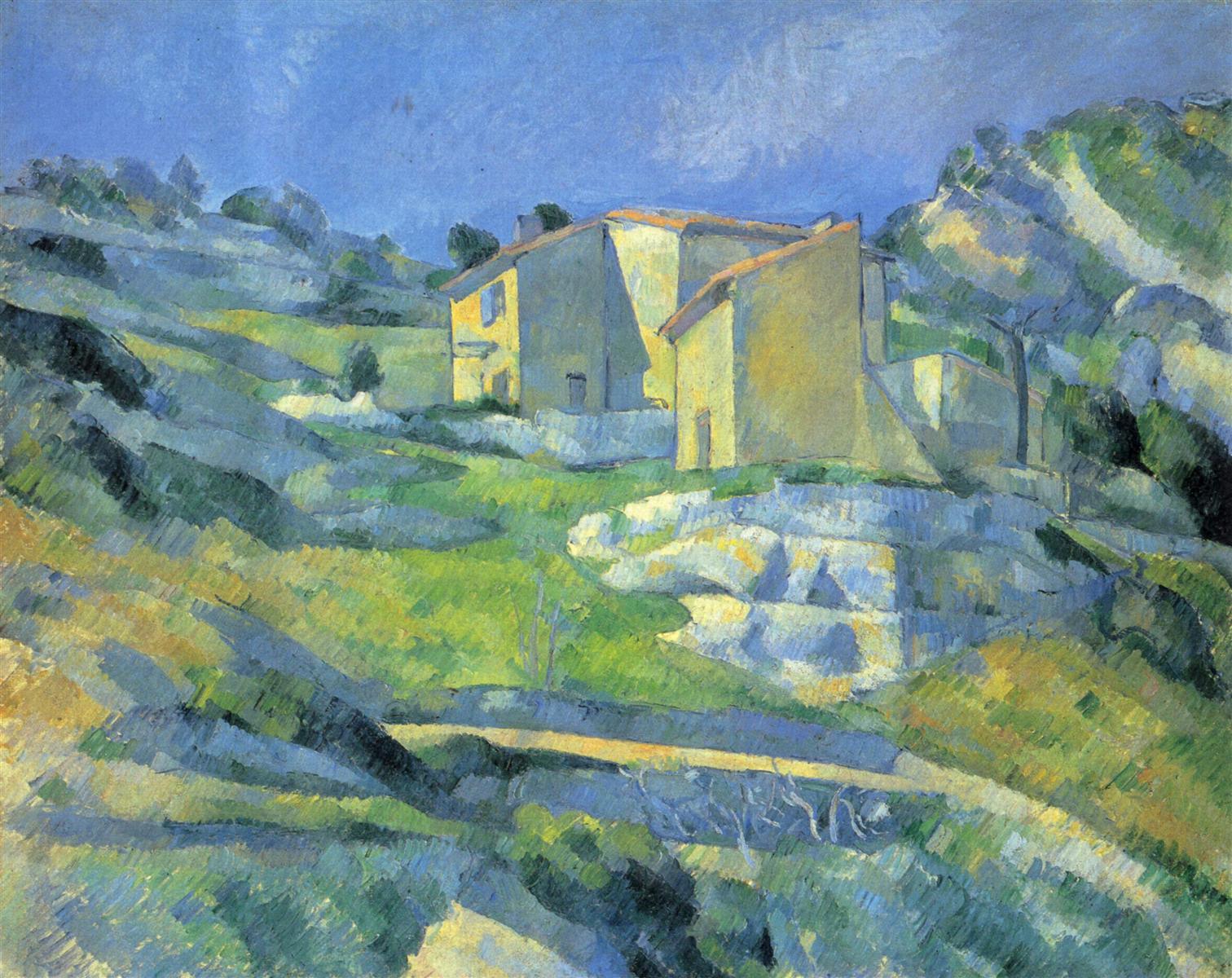

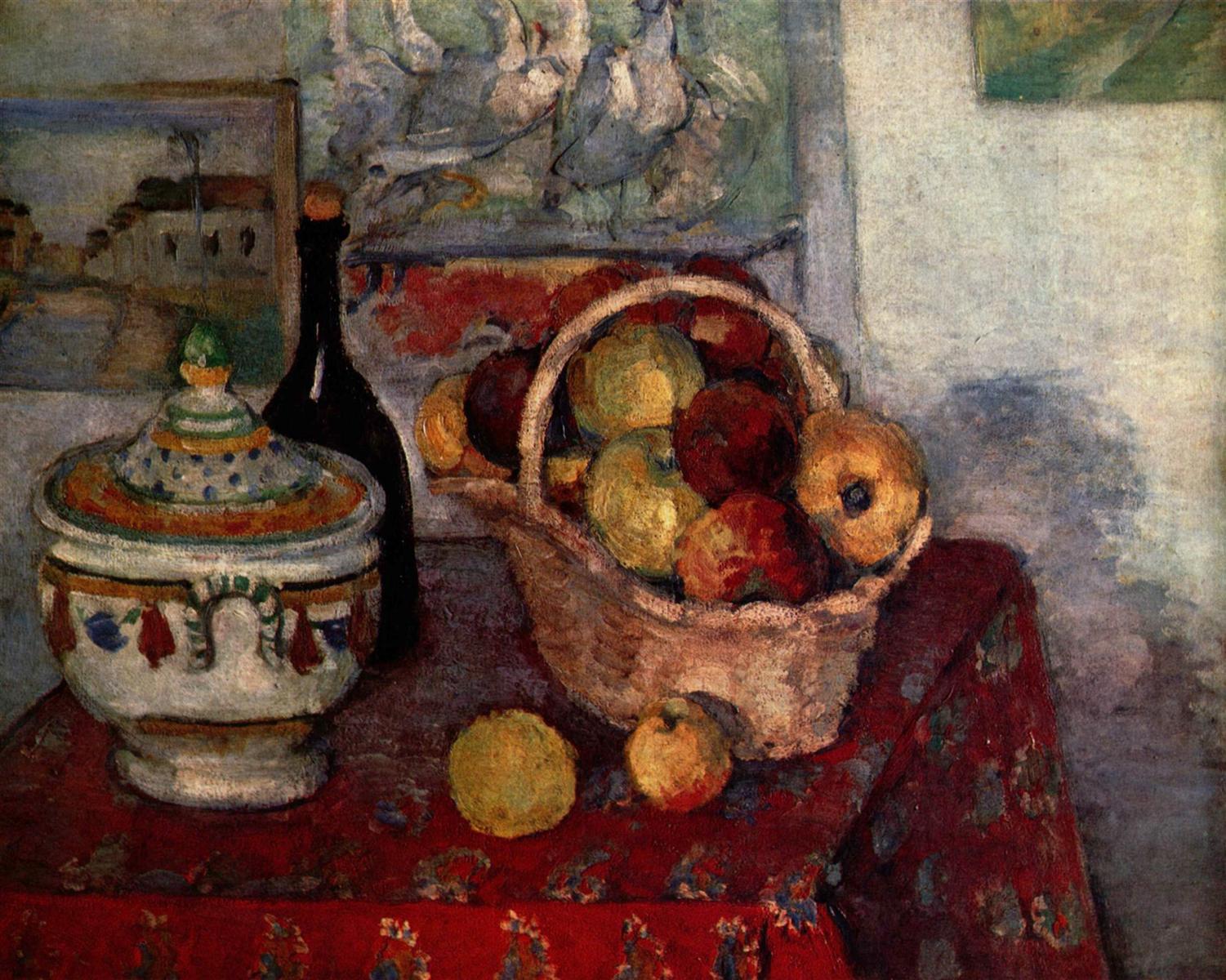

And she said some very good things about his manner of working (which one can decipher in an unfinished picture). “Here,” she said, pointing to one spot,

this he knew, and now he’s saying it (a part of an apple); right next to it there’s an empty space, because that was something he didn’t know yet. He only made what he knew, nothing else.

“What a good conscience he must have had,” I said. “Oh yes: he was happy, way inside somewhere …”

THE WORK

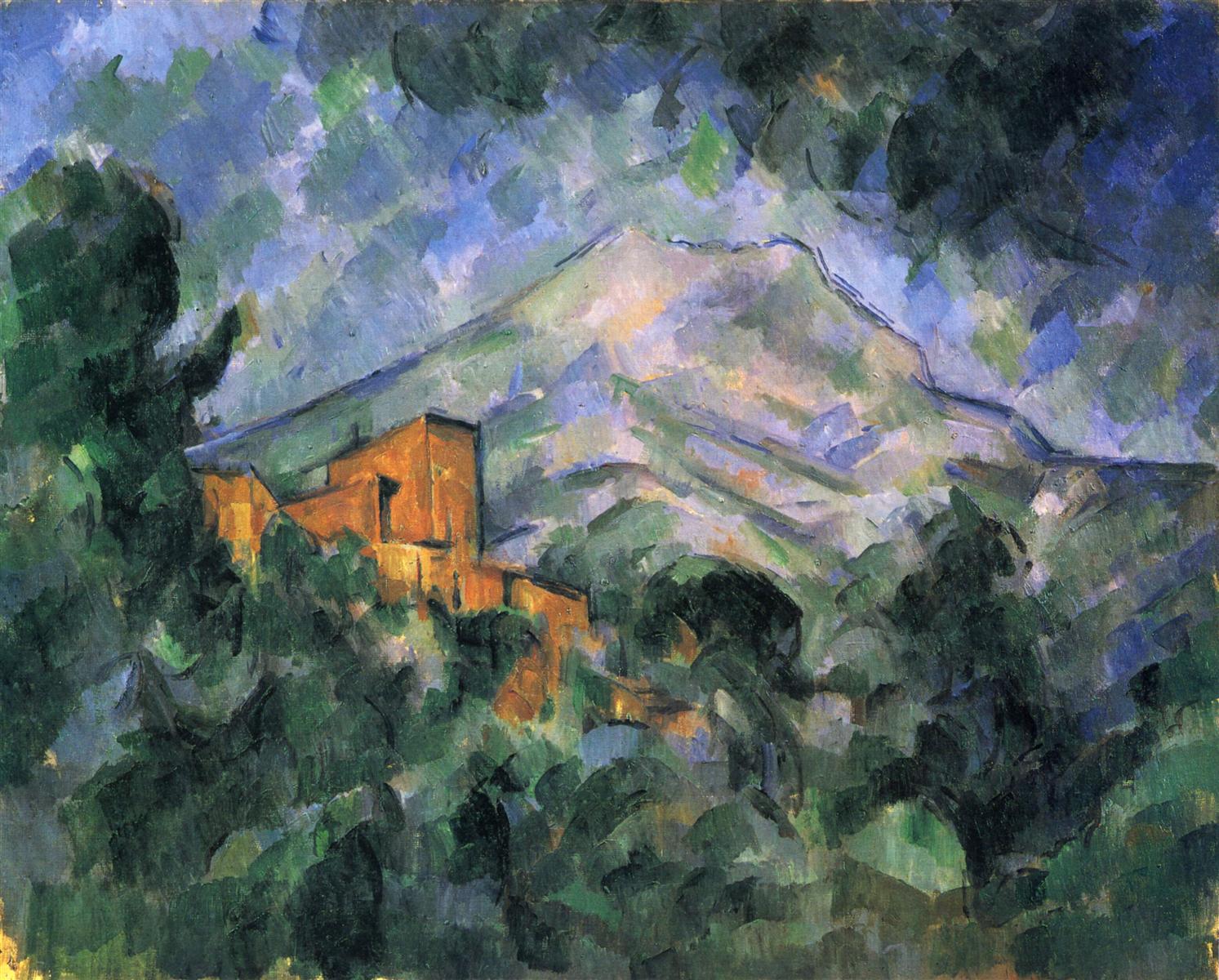

On October 9, Rilke described Cézanne’s process as “willful“.

What a distance to today’s insight (in the span of only three days, and one conversation with a painter friend): he only painted what he knew.

The very opposite of willfulness.

This is the essence of Cézanne process.

SEEING PRACTICE: LIKE A DOG (INDESCRIBABLE REALITY)

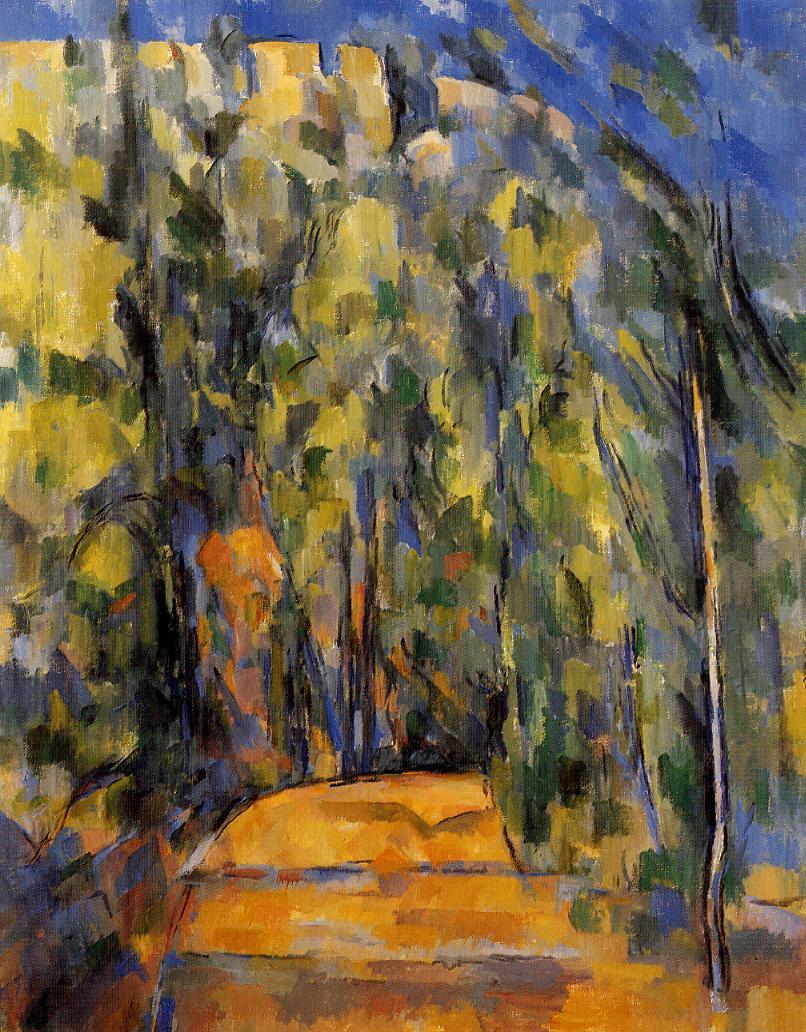

What does it mean: he sat there like a dog? I think it means LANGUAGE-LESS: without letting words interfere with his perception of reality, indescribable reality.

It must have been especially significant for Rilke, whose life’s work was to reenact reality in WORDS.

But it is also something nearly impossible to achieve to any of us, so deeply we are all caught in the internalized models of reality created by our languages. Most of the time, we only see things we can name.

What if we all could find some time and space today to see the world as it is, as vibrations of light and color, if even for a brief moment?