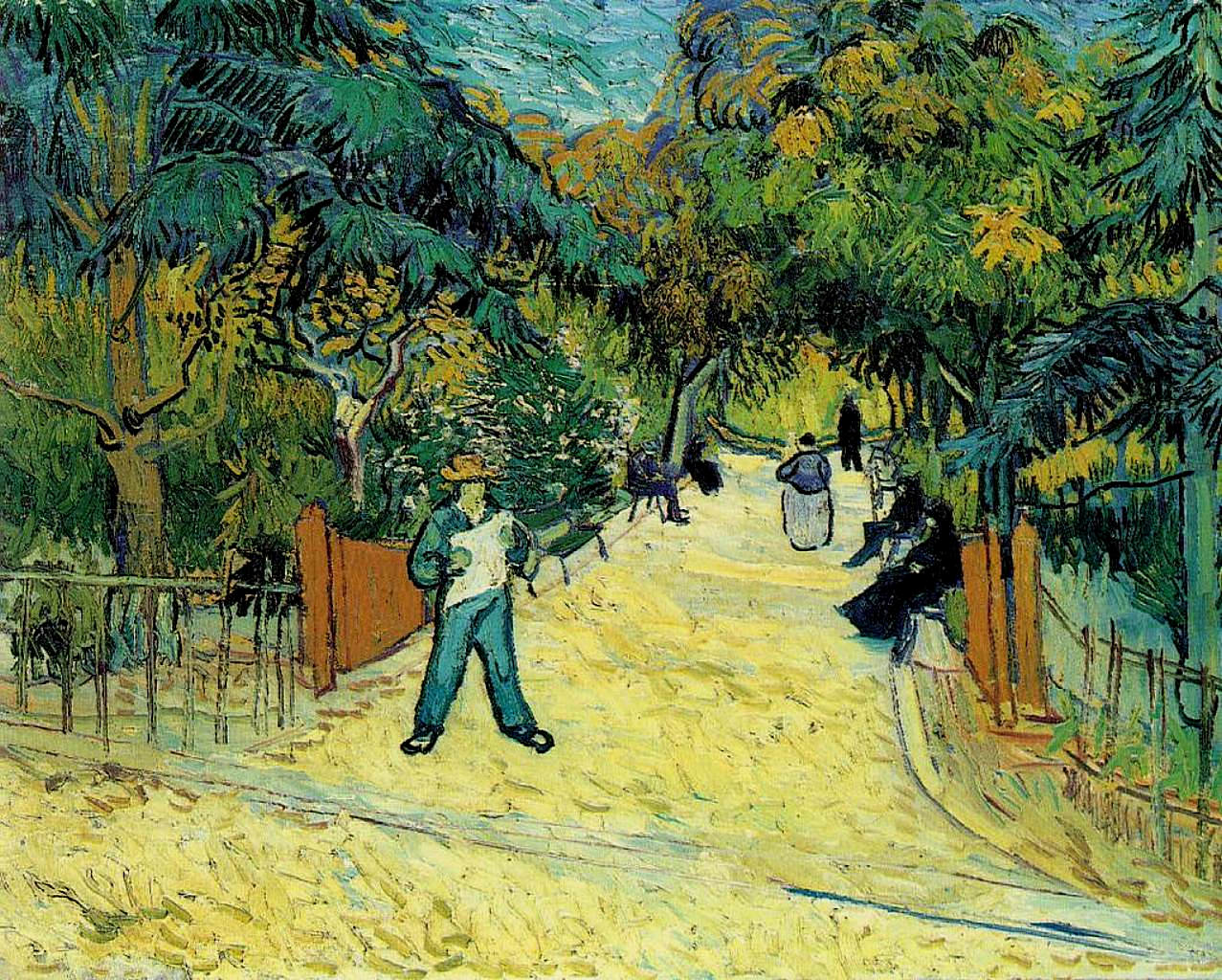

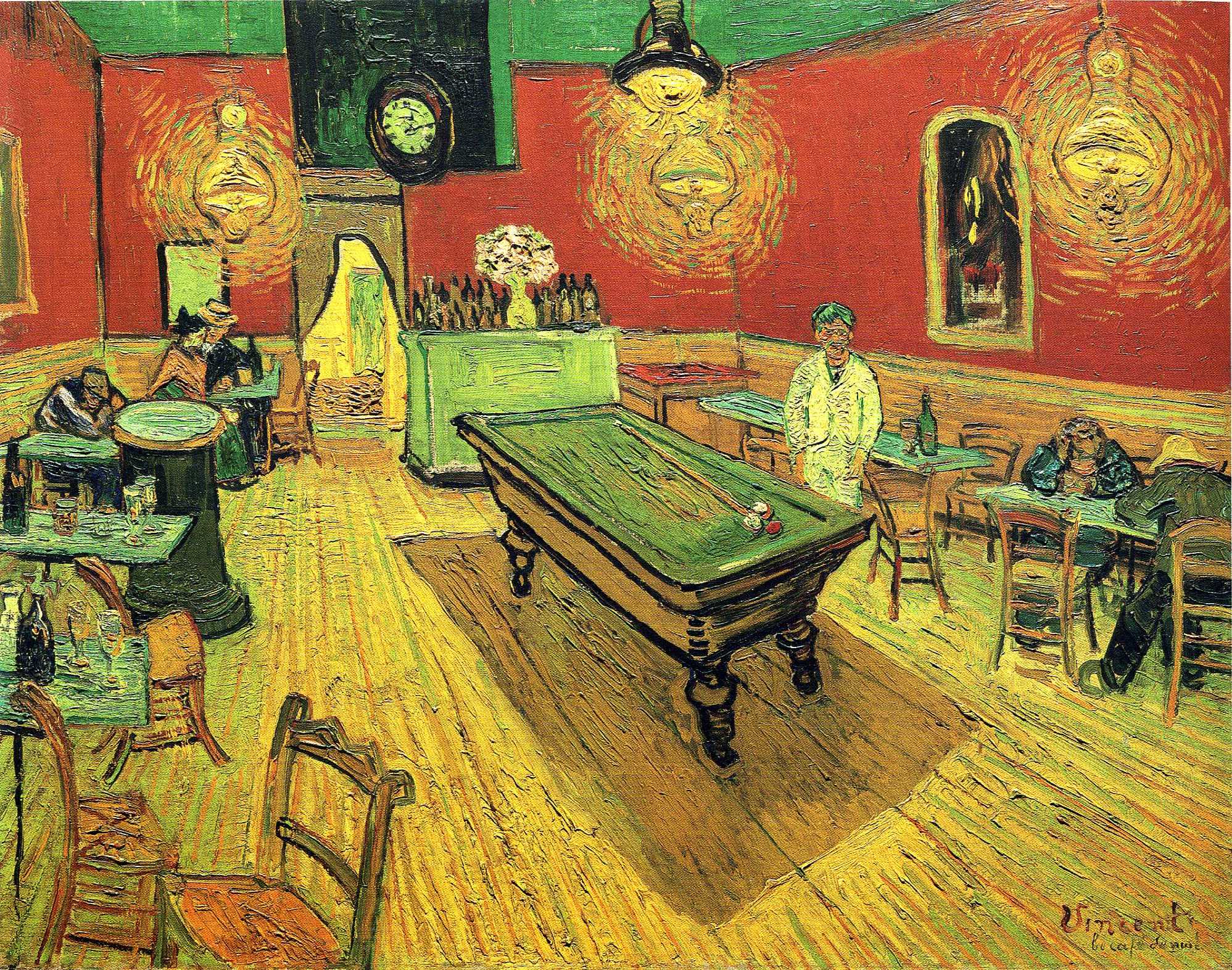

Rilke continues to describe van Gogh paintings he saw in Bernheim gallery.

OCTOBER 17 (Part 4)

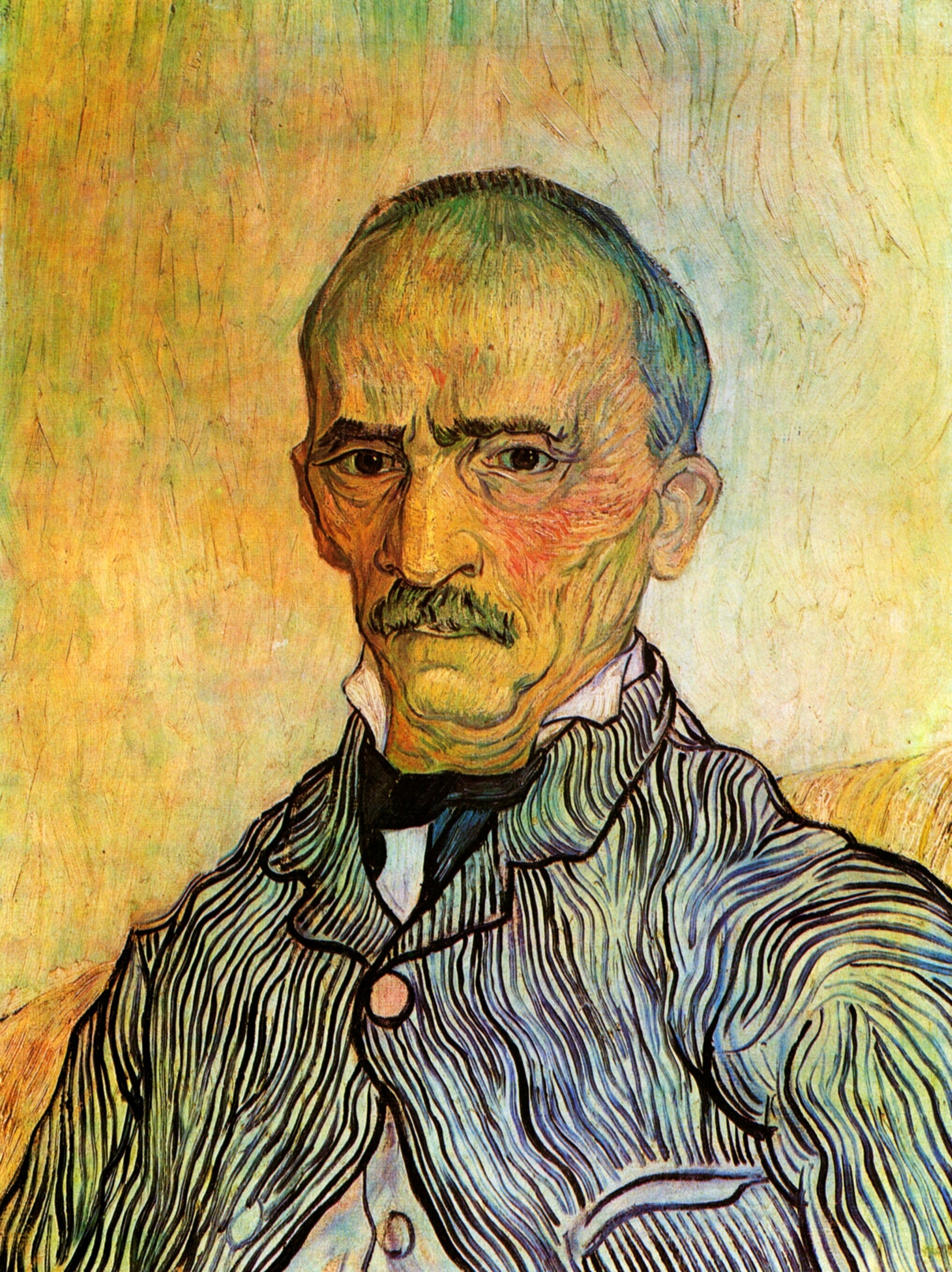

<…> A man’s portrait against a background (yellow and greenish yellow) that looks as if woven of fresh reed (but which, when you step back, is simplified to a uniform brightness):

An elderly man with a short-cropped, black-and-white mustache, sparse hair of the same color, cheeks indented beneath a broad skull:

the whole thing in black-and-white, rose, wet dark blue, and an opaque bluish white——except for the large brown eyes—

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

COLORS AND WORDS

“As if woven of fresh reed”: could one even imagine a more precise way to describe not only this particular painting, but ALL of van Gogh’s mature work?

SEEING PRACTICE: VAN GOGH

I remember the exact moment when I realized that what van Gogh shows us is a precise and truthful depiction of HIS visual reality, his unique experience of fluid, dynamic color. It was in Amsterdam, in front of this self-portrait.

Click the image to zoom in (on Van Gogh Museum site) and see this intensified reality, as though woven of fresh reed which borrowed its colors from the rainbow?