I think there was a conflict, a mutual struggle between the two procedures of, first, looking and confidently perceiving, and then of appropriating and making personal use of what has been perceived.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

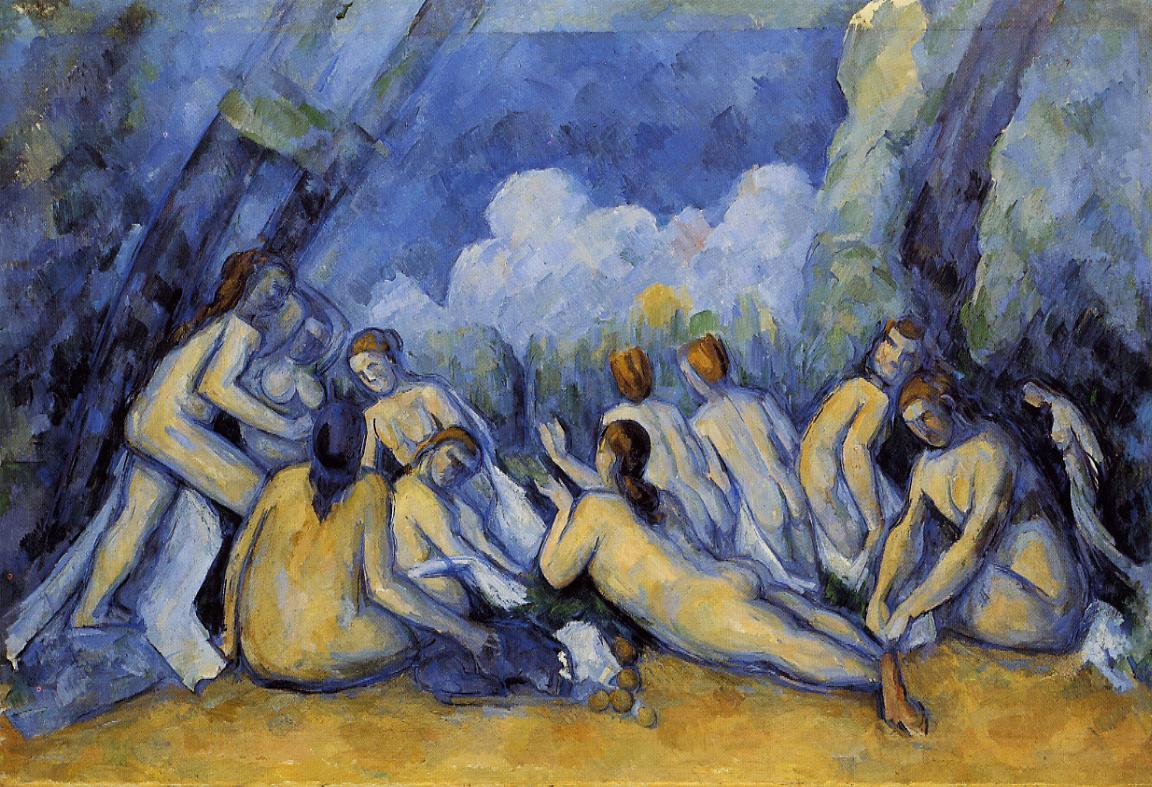

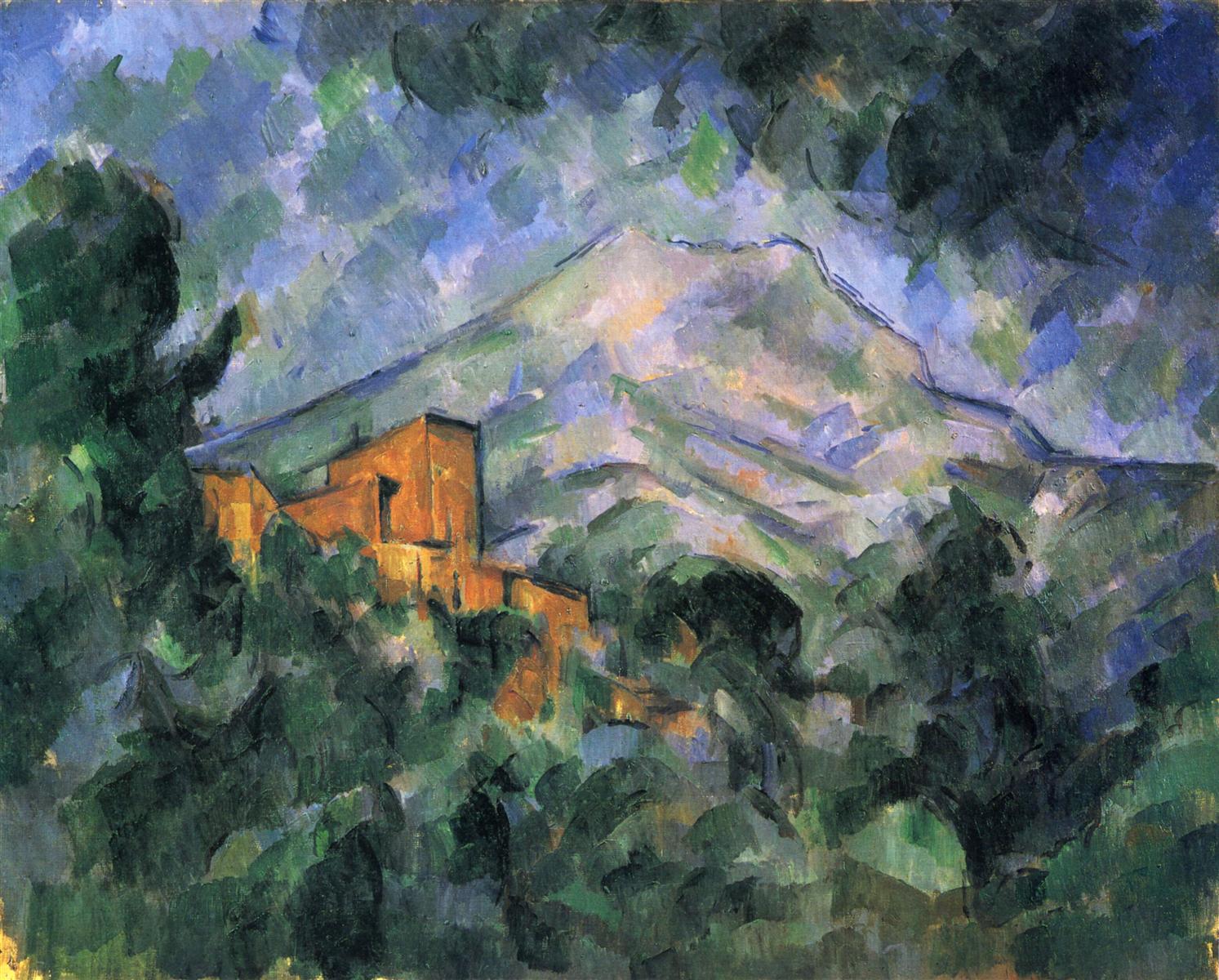

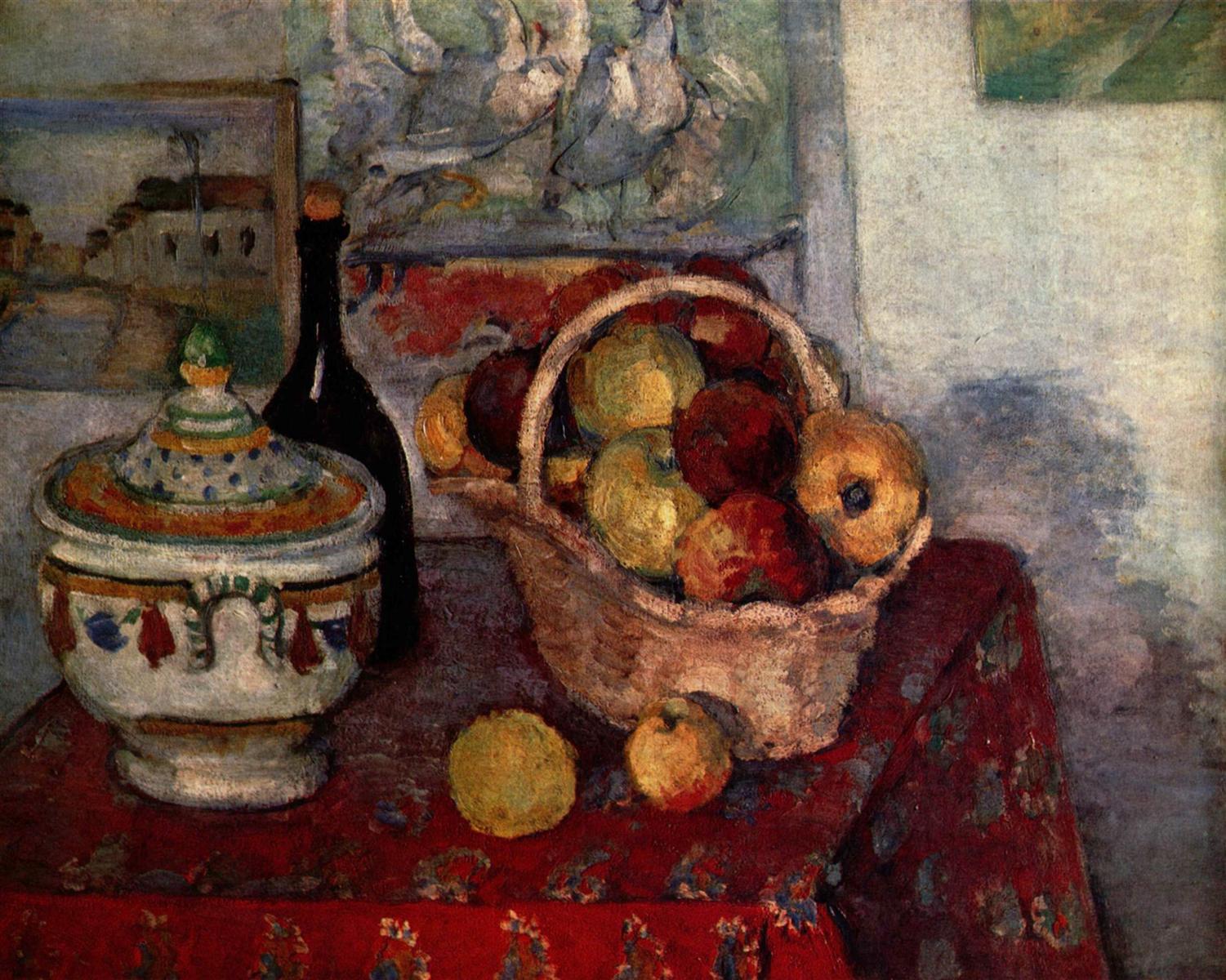

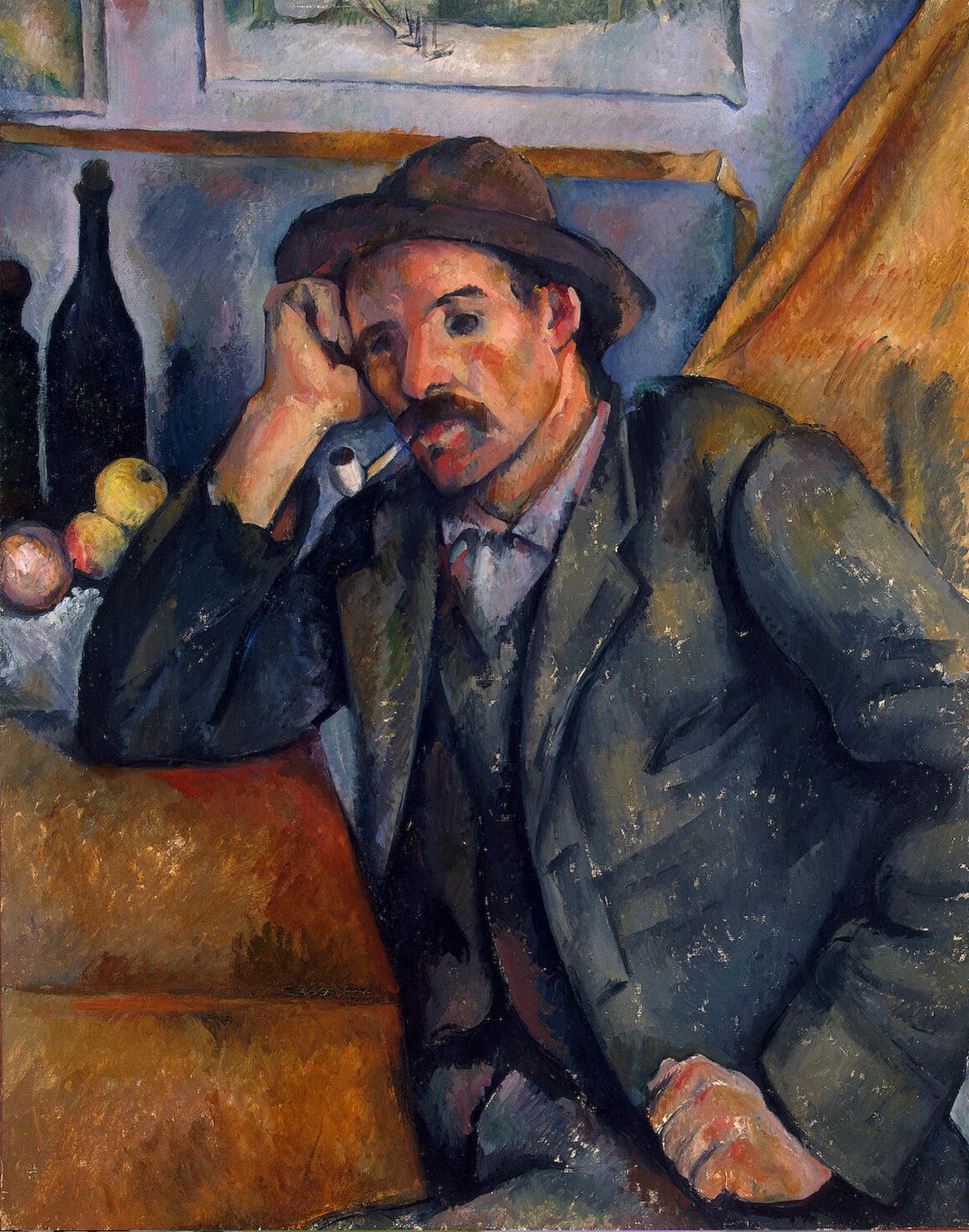

Cézanne created his own process of building up color in paintings from life. It was unlike anything the world of painting had seen before.

We know this process from his own letters, and from observations of fellow painters, and, most significantly, from his unfinished works.

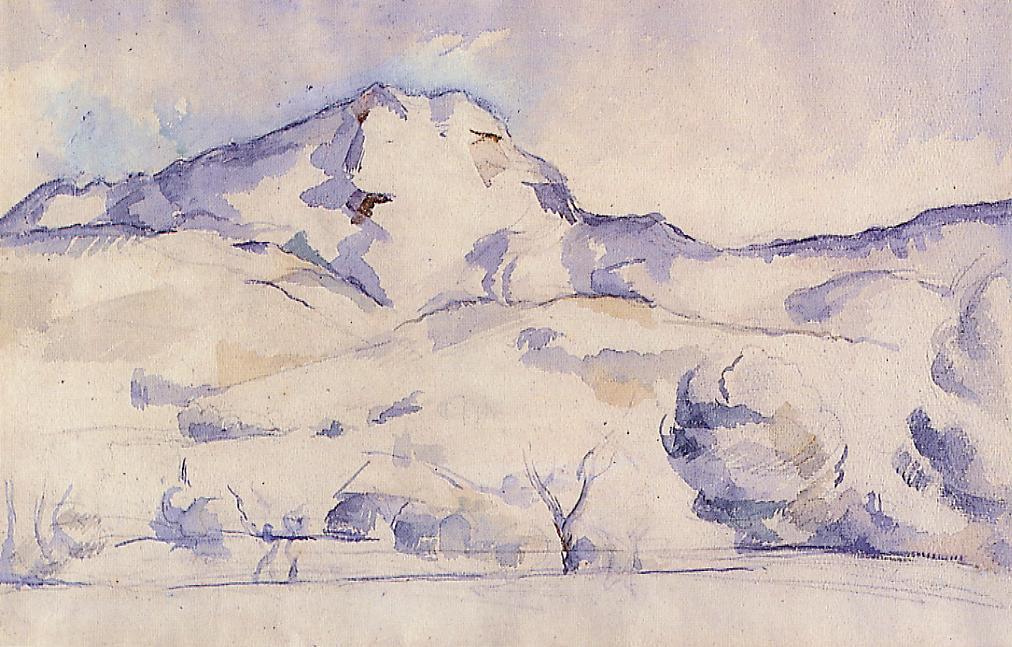

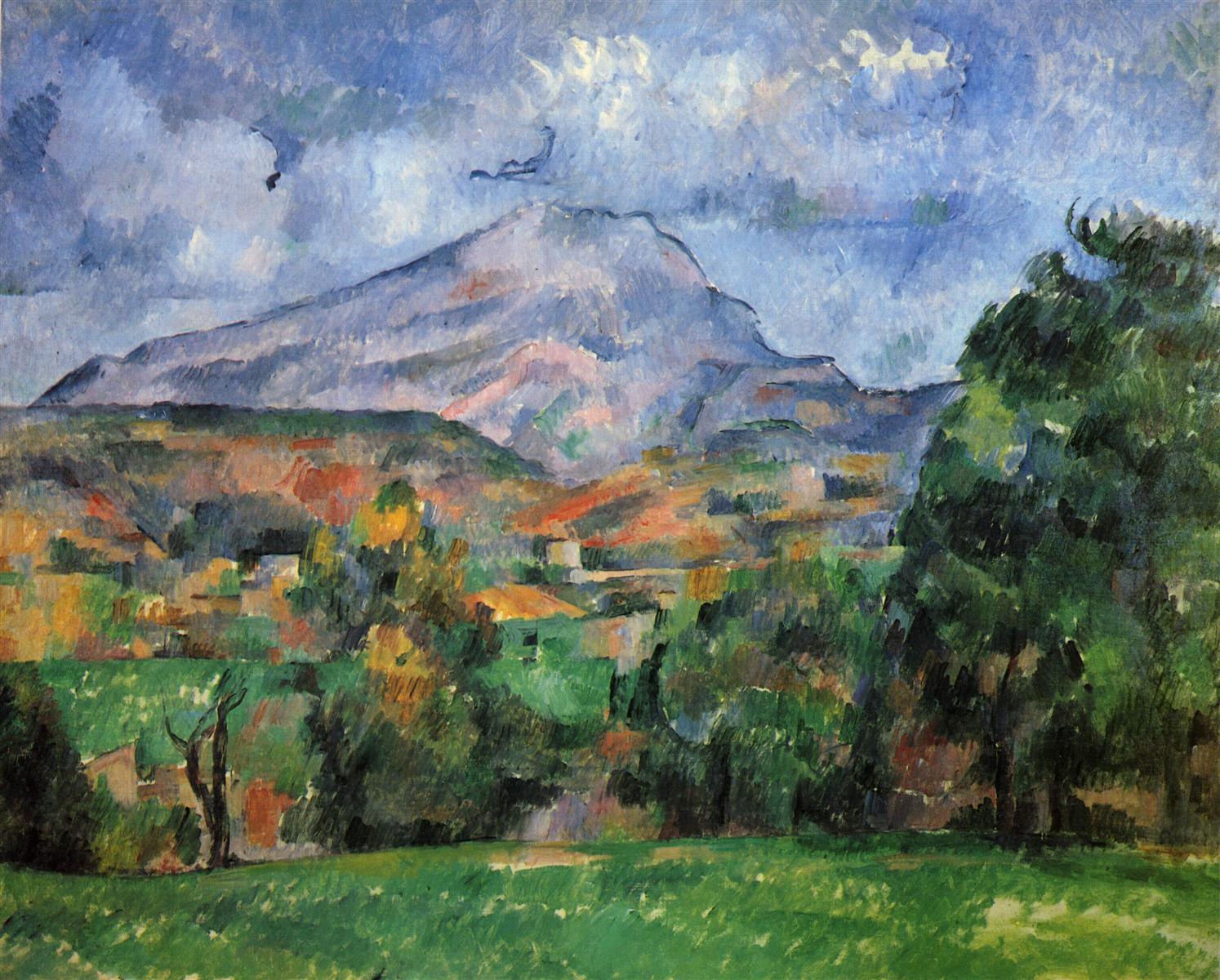

To complement Rilke’s description, I have included three paintings of the same motive, which show three different stages of his process.

October 9, 1907 (Part 2)

And all the while <…> he exacerbated the difficulty of his work in the most willful manner. While painting a landscape or a still life, he would conscientiously persevere in front of the subject, but approach it only by very complicated detours.

Beginning with the darkest tones, he would cover their depth with a layer of color that led a little beyond them, and keep going, expanding outward from color to color, until gradually he reached another, contrasting pictorial element, where, beginning at a new center, he would proceed in a similar way.

I think there was a conflict, a mutual struggle between the two procedures of, first, looking and confidently perceiving, and then of appropriating and making personal use of what has been perceived;

that the two, perhaps as a result of becoming conscious, would immediately start opposing each other, talking out loud, as it were, and go on perpetually interrupting and contradicting each other.

And the old man endured their discord, ran back and forth in his studio, which was badly lit because the builder had not found it necessary to pay attention to this strange old bird whom the people of Aix had agreed not to take seriously.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

INTERCOURSE OF COLORS. CONSCIOUS AWARENESS

At this point, Rilke doesn’t really understand the whys and wherefores of Cézanne’s process, but this will change in a few days.

His use of the word “willful” is particularly jarring to my ear, because there is simply no other way to achieve Cézanne’s realization of color. There is nothing willful, nothing random about this process.

Rilke’s note about the mutual struggle of two procedures touches a theme which he returns to, time and again: the artist’s CONSCIOUS AWARENESS of their own process and insights.

SEEING PRACTICE: ONENESS AND SEPARATION

Cézanne wrote to Émile Bernard on October 23, 1905:

So, old as I am, around seventy, the color sensations that create light are the cause of abstractions that do not allow me to cover my canvas, nor to pursue the delimitation of objects when their points of contact are subtle, delicate; the result of which is that my image or painting is incomplete.

On the other hand, the planes fall on top of one another, from which comes the neo-Impressionism that outlines [everything] in black, a defect that must be resisted with all one’s might. But consulting nature gives us the means of achieving this goal.

In the three paintings I attached to this letter, one can see this struggle between overlapping “color sensations” and black contours trying to hold everything together, or rather to keep objects apart.

I don’t see it as a struggle between perception and “appropriation”, as Rilke describes it. Rather, it is a struggle between two modes of perception, one that sees separate objects, and one that sees only unified vibrations of color.