OCTOBER 24, 1907 (Part 3)

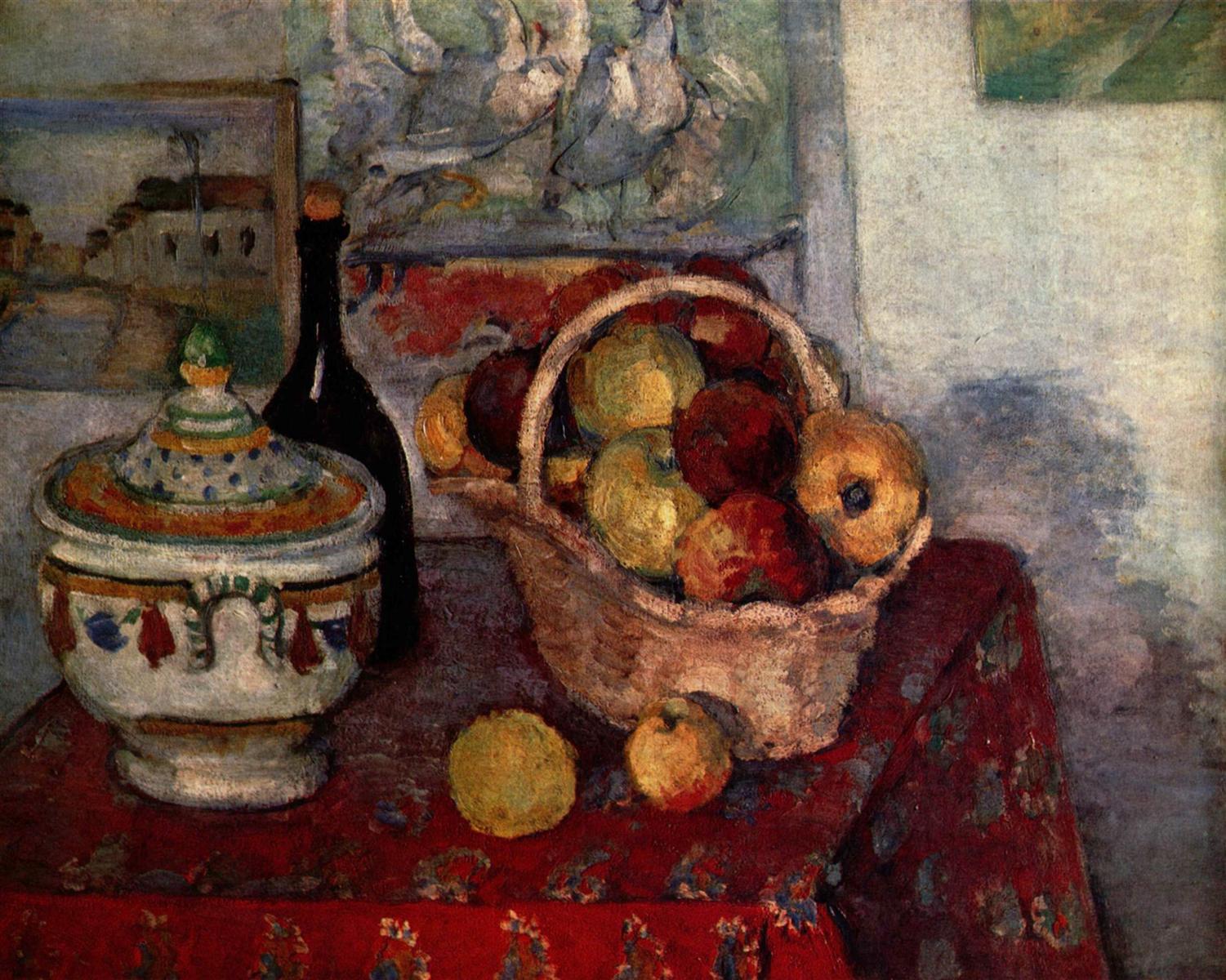

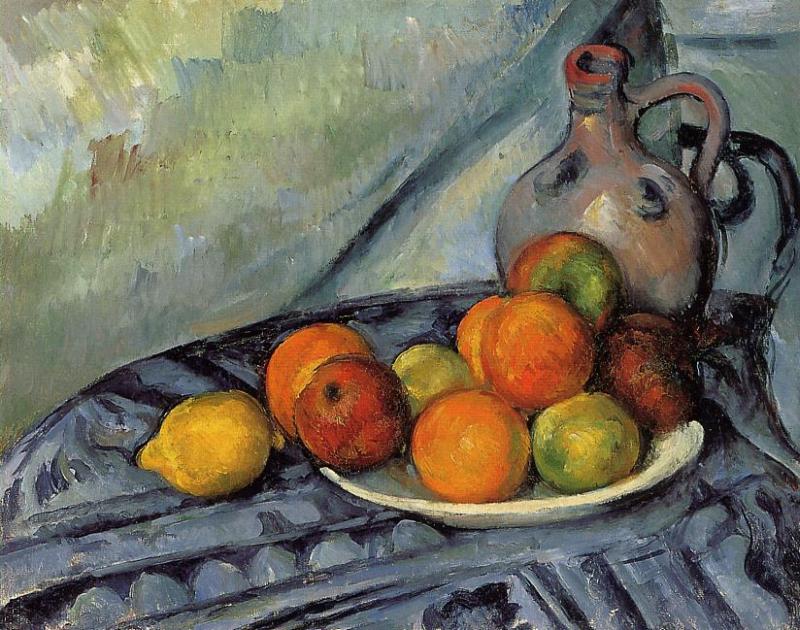

Although one of his idiosyncrasies is to use pure chrome yellow and burning lacquer red in his lemons and apples, he knows how to contain their loudness within the picture: cast into a listening blue, as if into an ear, it receives a silent response from within, so that no one outside needs to think himself addressed or accosted.

His still lifes are so wonderfully occupied with themselves.

The frequently used white cloth, for one, which has a peculiar way of soaking up the predominant local color, and the things placed upon it now adding their statements and comments, each with its whole heart.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

STORYLINE: Intercourse of colors

On October 21, Rilke wrote about painting as “something that takes place among colors”, their mutual intercourse being the whole of painting.

Here, this insight unfolds itself through the metaphor of painting as conversation among colors, complete with listening, responding, statements and comments.

Colors talk among themselves, and all the spectator has to do is witness this conversation.

SEEING practice: Cezanne

There are two “listening” colors here, the humble, unobtrusive blue of the first still life, and the white cloth of the second. Do you see how different their listening is?