To his immensely painterly eye it didn’t hold up as a color: he went to the core of it and found that it was violet there or blue or reddish or green.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

OCTOBER 24, 1907 (Part 1)

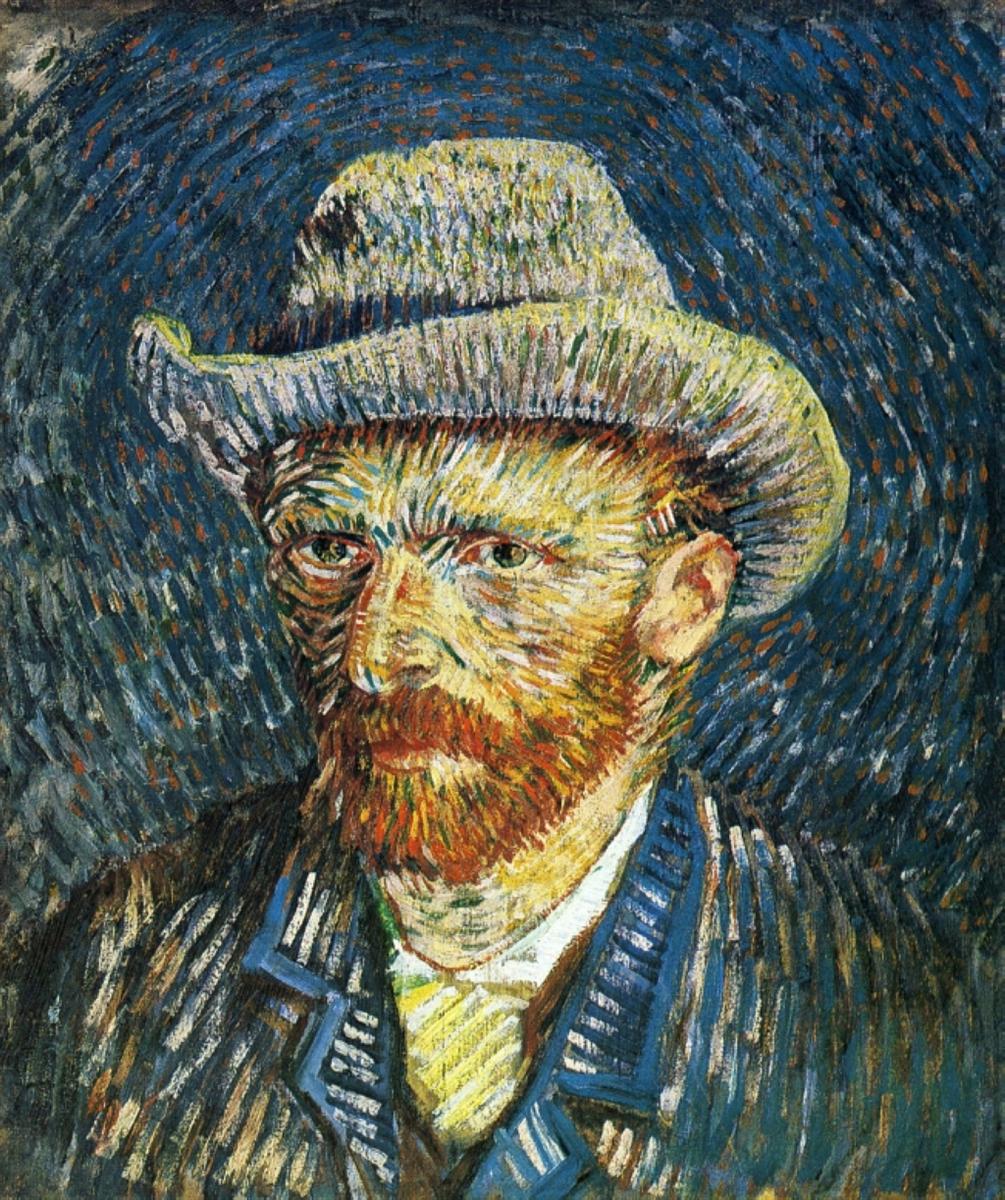

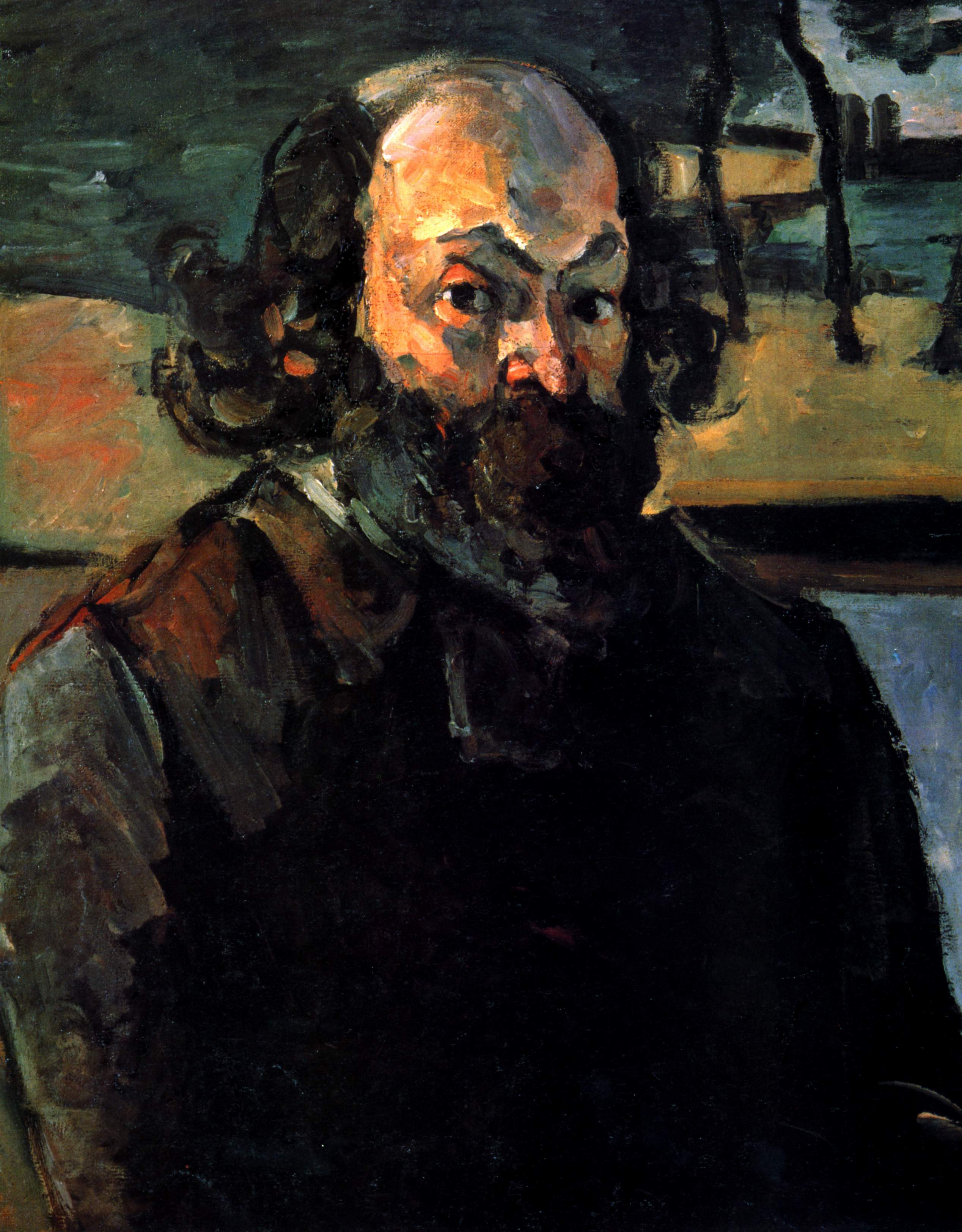

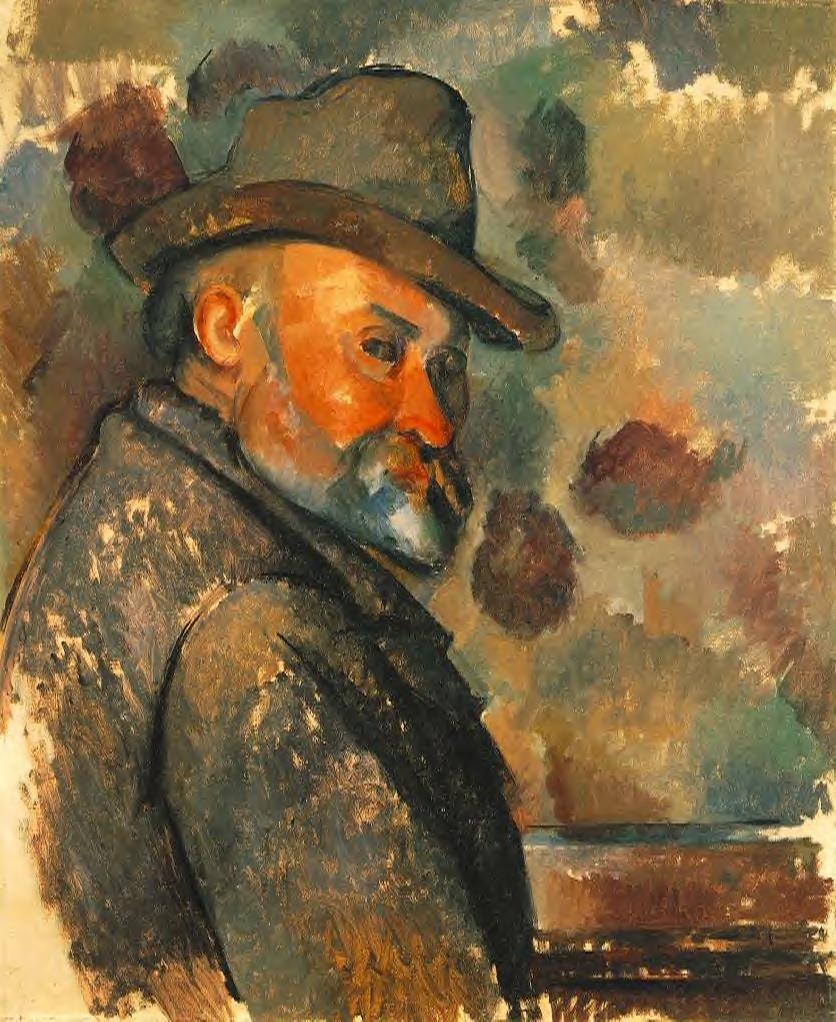

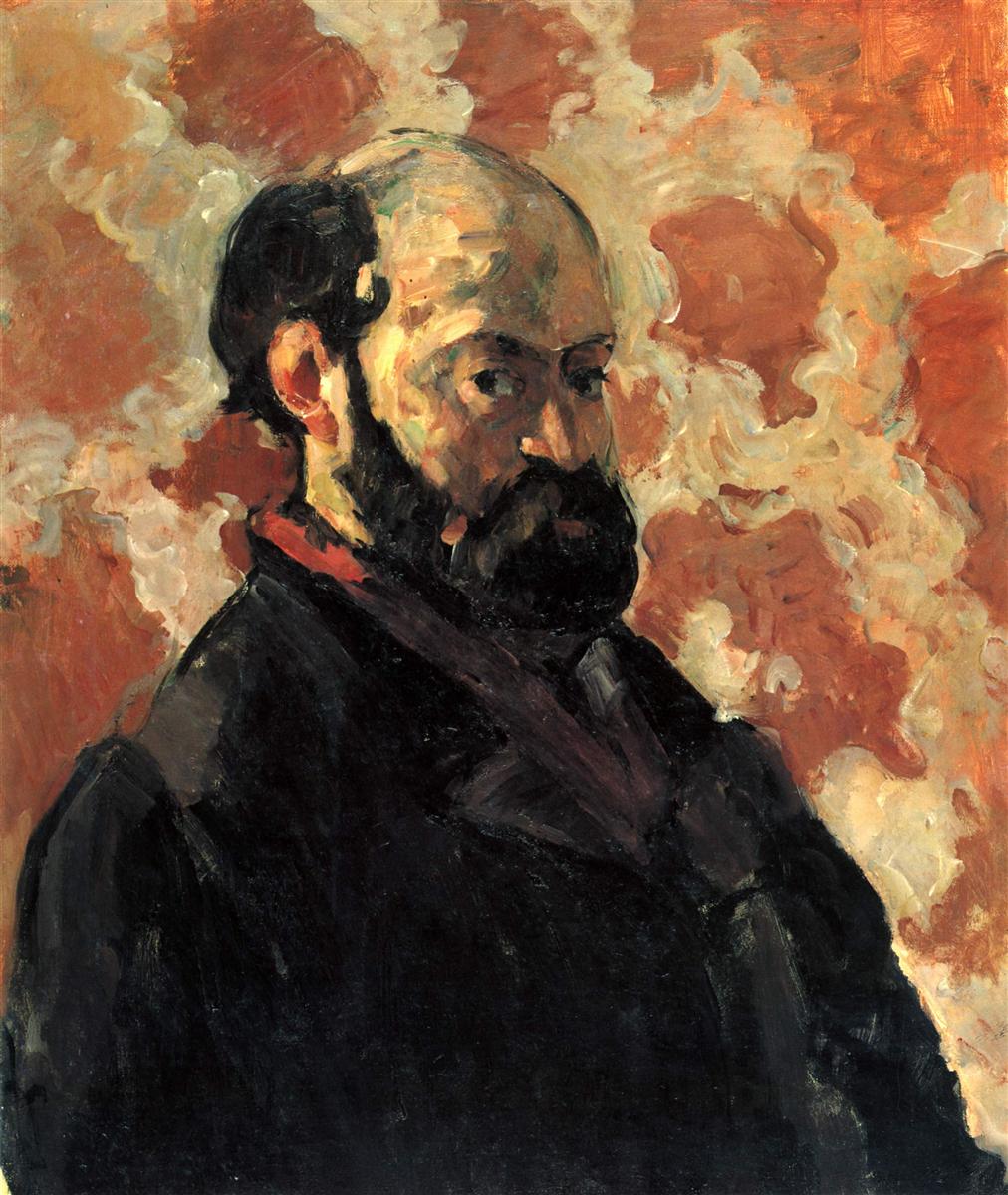

… I said: gray—yesterday, when I described the background of the self-portrait, light copper obliquely crossed by a gray pattern.

I should have said: a particular metallic white, aluminum or something similar, for gray, literally gray, cannot be found in Cézanne’s pictures.

To his immensely painterly eye it didn’t hold up as a color: he went to the core of it and found that it was violet there or blue or reddish or green.

He particularly likes to recognize violet (a color which has never been opened up so exhaustively and so variously) where we only expect and would be contented with gray;

but he doesn’t relent and pulls out all the violet hues that had been tucked inside, as it were; the way certain evenings, autumn evenings especially, will address the graying facades directly as violet, and receive every possible shade for an answer, from a light floating lilac to the heavy violet of Finnish granite.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

STORYLINE: Intercourse of colors

If I were to name my absolute favorite in this extraordinary sequence of letters, this may well be the one.

It embodies and reenacts the very essence of painting: its ability to open our eyes to what we haven’t seen before, couldn’t even imagine seeing.

And Rilke not only describes, but intensifies this effect: what one might have missed in Cézanne, one cannot miss now, once it is named.

And the way he compares Cézanne to autumn evenings, in his ability to pull out colors from nature, to make the nature respond to the painter’s eye, just like it responds to the sunlight…

SEEING PRACTICE: GREY

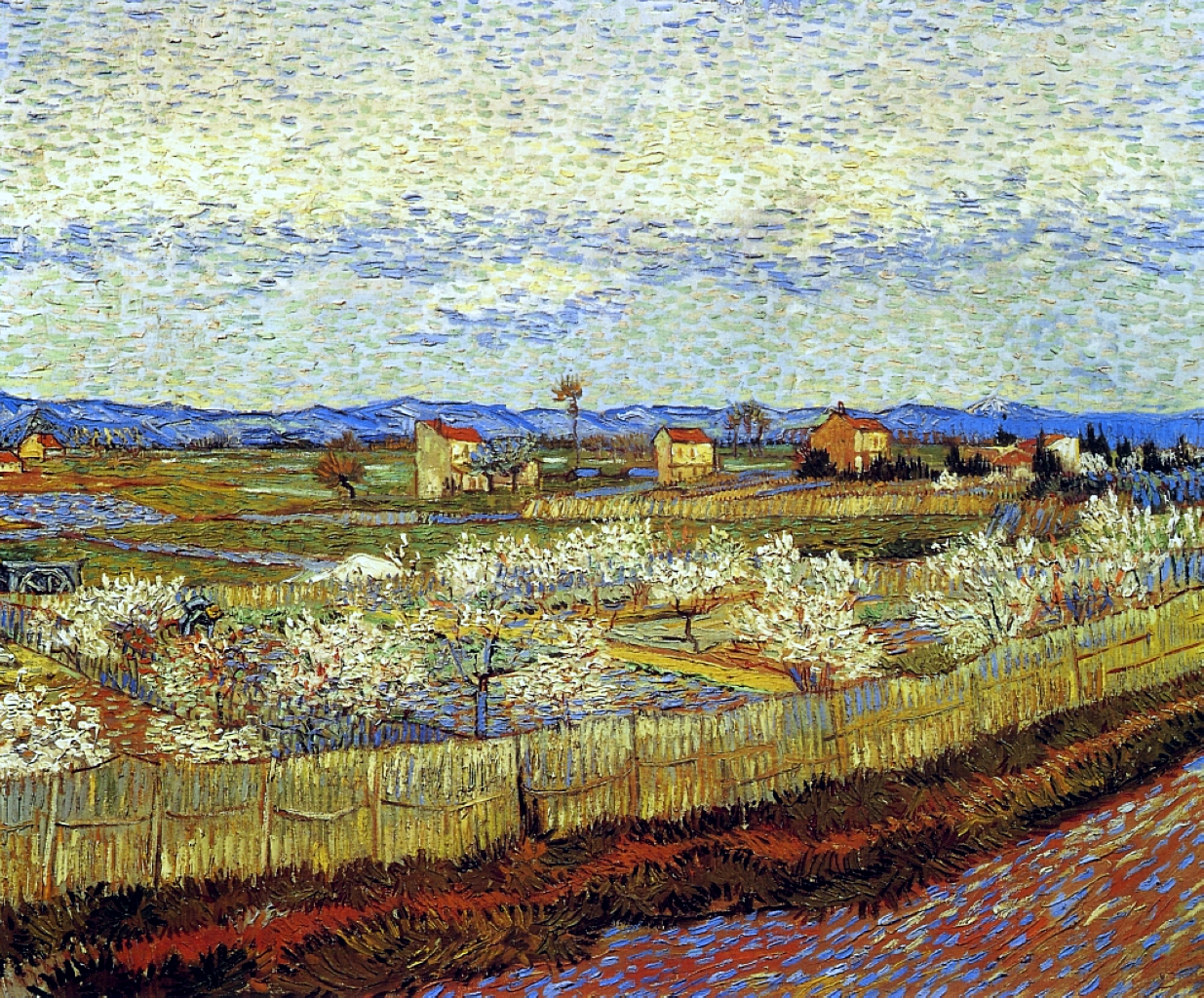

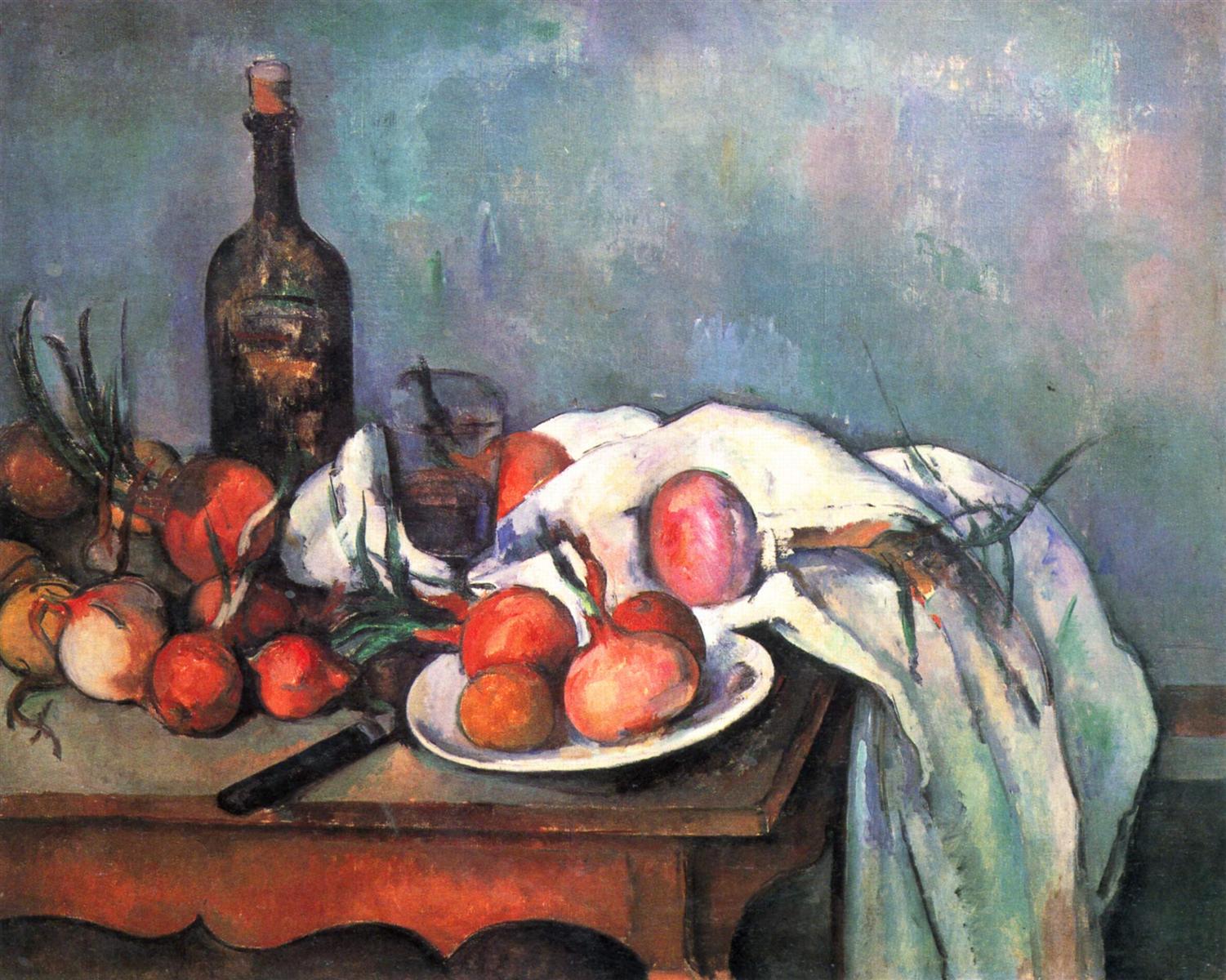

Even the imperfections of reproductions conspire to help us see what Rilke is talking about here.

In the still life above, the reproduction pulls out and exaggerates the colors hidden in Cézanne grays. If you click to zoom in, you will see a more muted (and closer to life) image; but zoom in on the gray areas, on all the secret hues of grey. Zoom in on the landscape to see how difficult it is to transmit this experience of grey in reproduction.

And what about “real life”? Can one “zoom in” on its grey areas to recognize the hues which so often stay unseen, both literally and metaphorically?