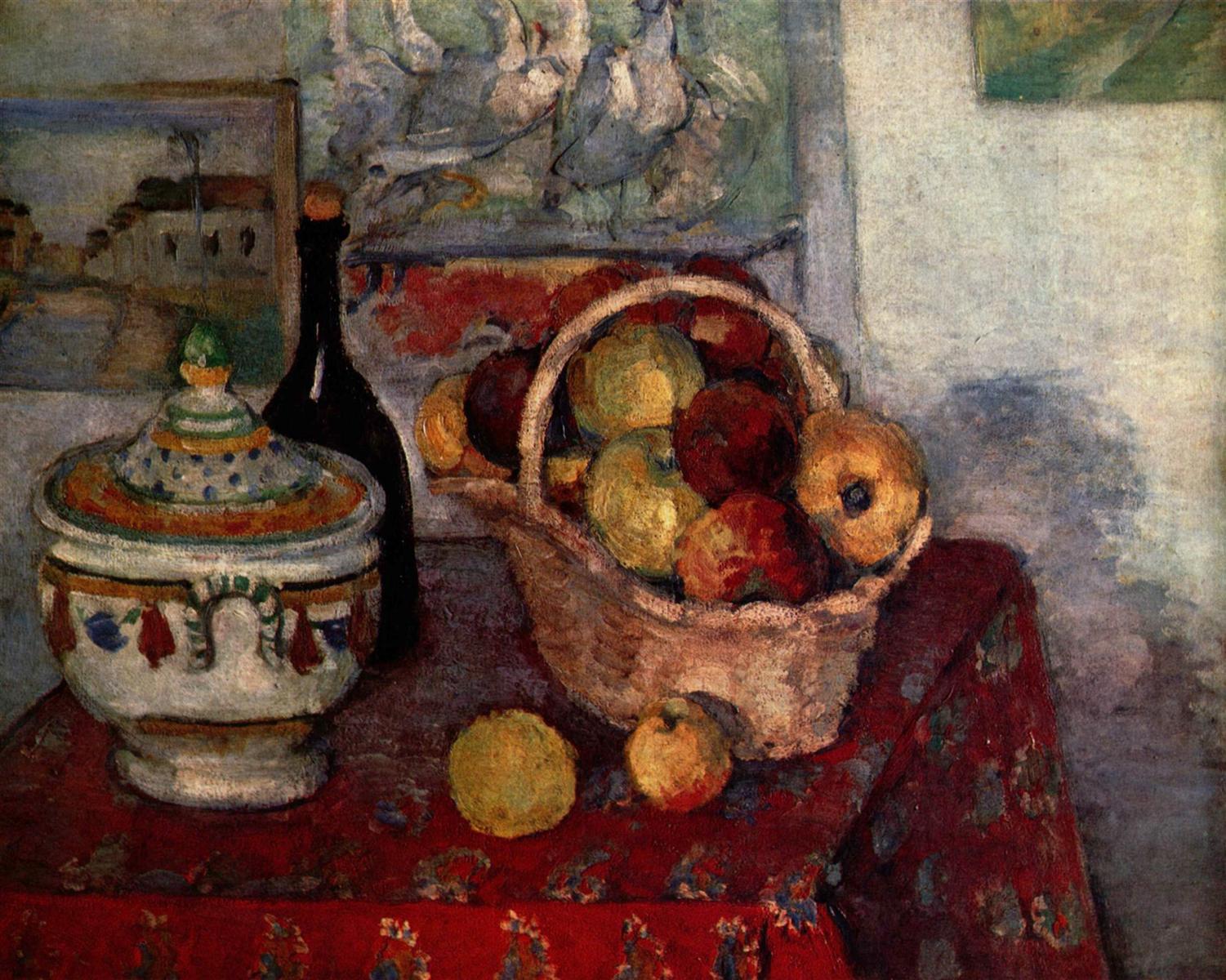

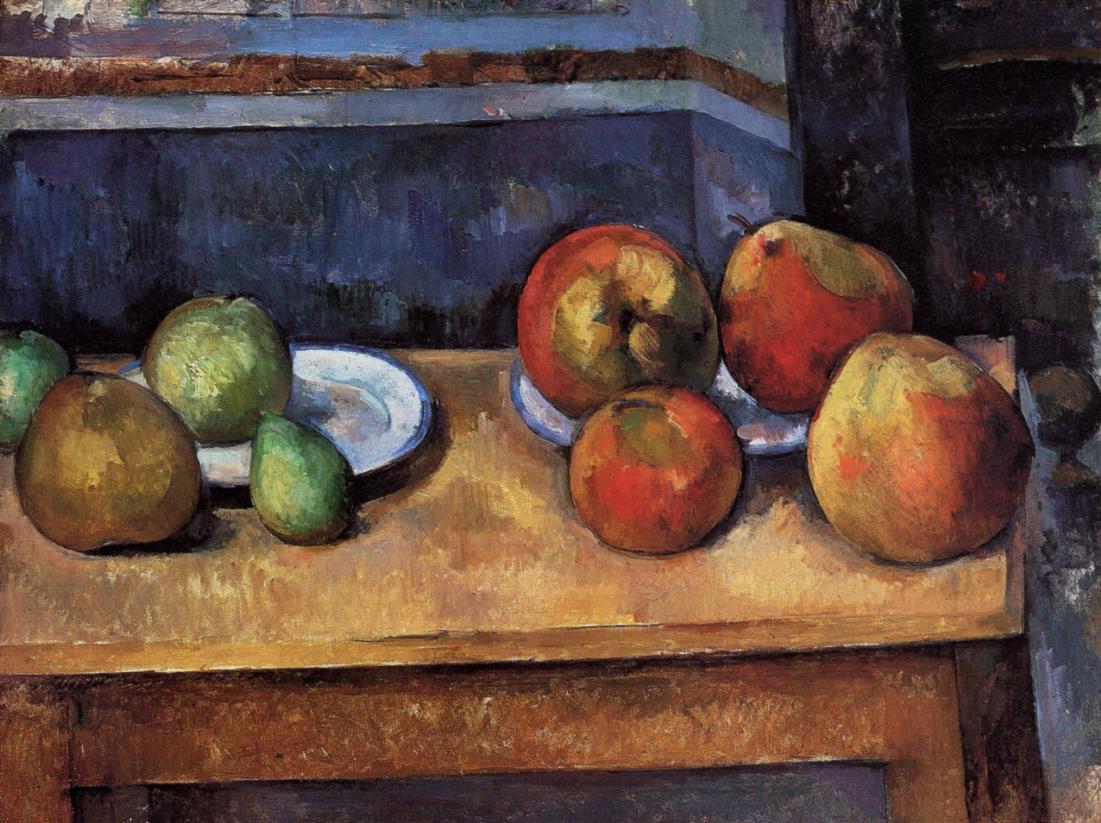

In Cézanne they cease to be edible altogether, that’s how thing-like and real they become, how simply indestructible in their stubborn thereness.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

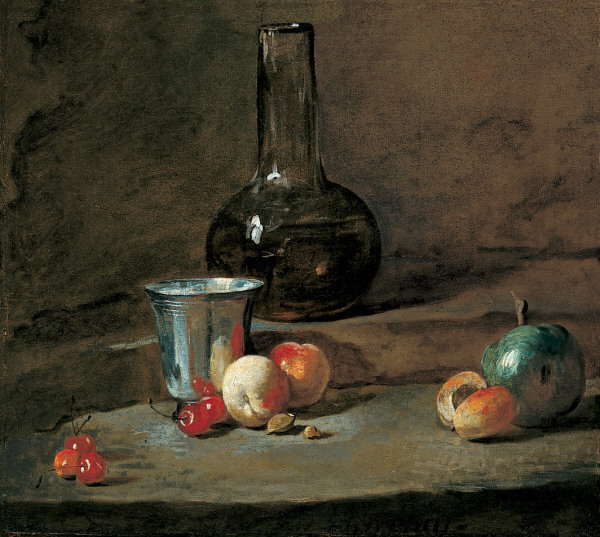

Earlier in this letter, Rilke wrote about the evolution of the colour blue in painting, and Chardin as the intermediary on the path from the eighteenth-century blue to Cézanne’s blue.

Here, he traces a fundamentally similar development in the way objects are treated in painting.

OCTOBER 8, 1907 (Part 3)

… Chardin was the intermediary in other respects, too; his fruits are no longer thinking of a gala dinner, they’re scattered about on kitchen tables and don’t care whether they are eaten beautifully or not.

In Cézanne they cease to be edible altogether, that’s how thing-like and real they become, how simply indestructible in their stubborn thereness.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

POVERTY

In this letter, the theme of poverty may not be obvious (elsewhere, Rilke writes that Cézanne’s apples are all “cooking apples”; that is, a poor man’s apples). Here, it is not about poverty in the narrow, literal sense, but about the lack of pretenses, cultural symbolisms, refinements — these hallmarks of civilized, wealthy society.

Cézanne’s apples are simply things, seen and painted as they are, without any human meanings attached or implied (including being edible).

SEEING PRACTICE: SIMPLY THINGS (APPLES)

We go through life projecting meanings and emotions onto things, and not even noticing that we do it most of the time. These projections shape our reality, which essentially means that they prevent us from SEEING reality.

Just notice how hard it can be to see an apple as it is, in its plain, objective thereness, without attaching any words and sensations to it, so that it is not tasty, or fresh, or healthy, or beautiful, or anything like this at all. It is neither a sign of autumn harvest, nor the symbol of the fall of man. It simply is.

It is in this plain THERENESS that Rilke feels affinity with Cézanne.