… I believe that the only time I lived without loss were the ten days after Ruth’s birth, when I found reality as indescribable, down to its smallest details, as it surely always is…

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

In this letter, Rilke refers to the birth of his daughter, Ruth (1901), and its effect on his state of being.

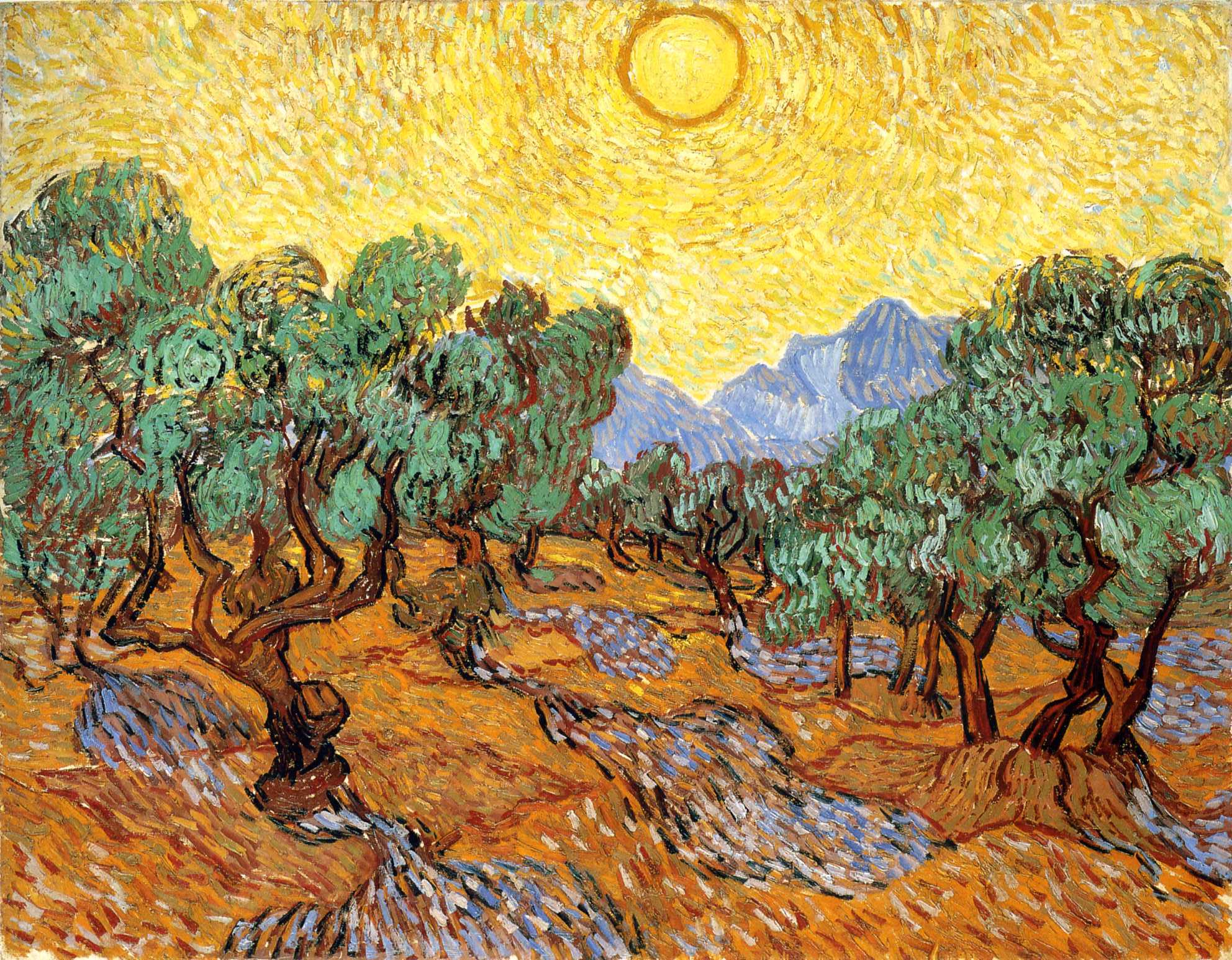

I looked around for a painting which would embody this effect, and found this painting by Cézanne, which I had never seen before, nor even known of its existence.

It is so unusual for Cézanne, so utterly unlike any other portraits of his wife, so filled with humble tenderness, so in resonance with Rilke’s letter (although he never mentions it). Perhaps, Cézanne, too, experienced reality differently just after the birth of his child…

SEPTEMBER 13, 1907

One lives so badly, because one always comes into the present unfinished, unable, distracted. I cannot think back on any time of my life without such reproaches and worse.

I believe that the only time I lived without loss were the ten days after Ruth’s birth, when I found reality as indescribable, down to its smallest details, as it surely always is.

<…>

Now that winter’s already impending here. Those vaporous mornings and evenings are already starting, where the sun is merely the place where the sun used to be, and where in the yards all the summer flowers, the dahlias and the tall gladiolas and the long rows of geraniums shout the contradiction of their red into the mist.

This makes me sad. It brings up desolate memories, one doesn’t know why: as if the music of the urban summer were ending in dissonance, in a mutiny of all its notes; perhaps just because one has already once before taken all this so deeply into oneself and read its meanings and made it part of oneself, without ever actually making it.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

STORYLINE: LANDSCAPES OF WORDS. PRESENCE

As though in contradiction to his own words about “indescribable reality”, Rilke concludes the letter with one of his striking LANDSCAPES-IN-WORDS, which recreate the visual reality in one’s mind’s eye.

As these landscapes appear in the letters, one after another, we see (or hear?) how Rilke’s vision changes and expands as he takes in and absorbs Cézanne’s way of seeing. This one is not yet quite informed by Cézanne, more “impressionist” in style and quality.

PRESENCE, which appeared in the very first letter as a quality of space, now re-emerges as a quality of life-altering moments in time.

SEEING PRACTICE: Renoir’s indescribable reality

As we go through our days, we don’t really see reality as indescribable. We seem to have names for everything we encounter, often more than one. But in the space of a painting, we glimpse the inadequacy of these words: just how little of what Renoir’s landscape contains and shows can we describe in things-naming words?

But reality is just as indescribable; the trick is to open one’s eyes to see it.