… he (van Gogh) wanted or knew or experienced this and that; that blue called for orange and green for red: that, secretly listening in his eye’s interior, he had heard such things spoken, the inquisitive one.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

Rilke continues his thoughts on the conflict between artistic insight and the artist’s conscious awareness of it, their ability to put their insights into words (here is the first part of the letter). The “writing painter” he mentions here is Émile Bernard.

OCTOBER 21, 1907 (Part 2)

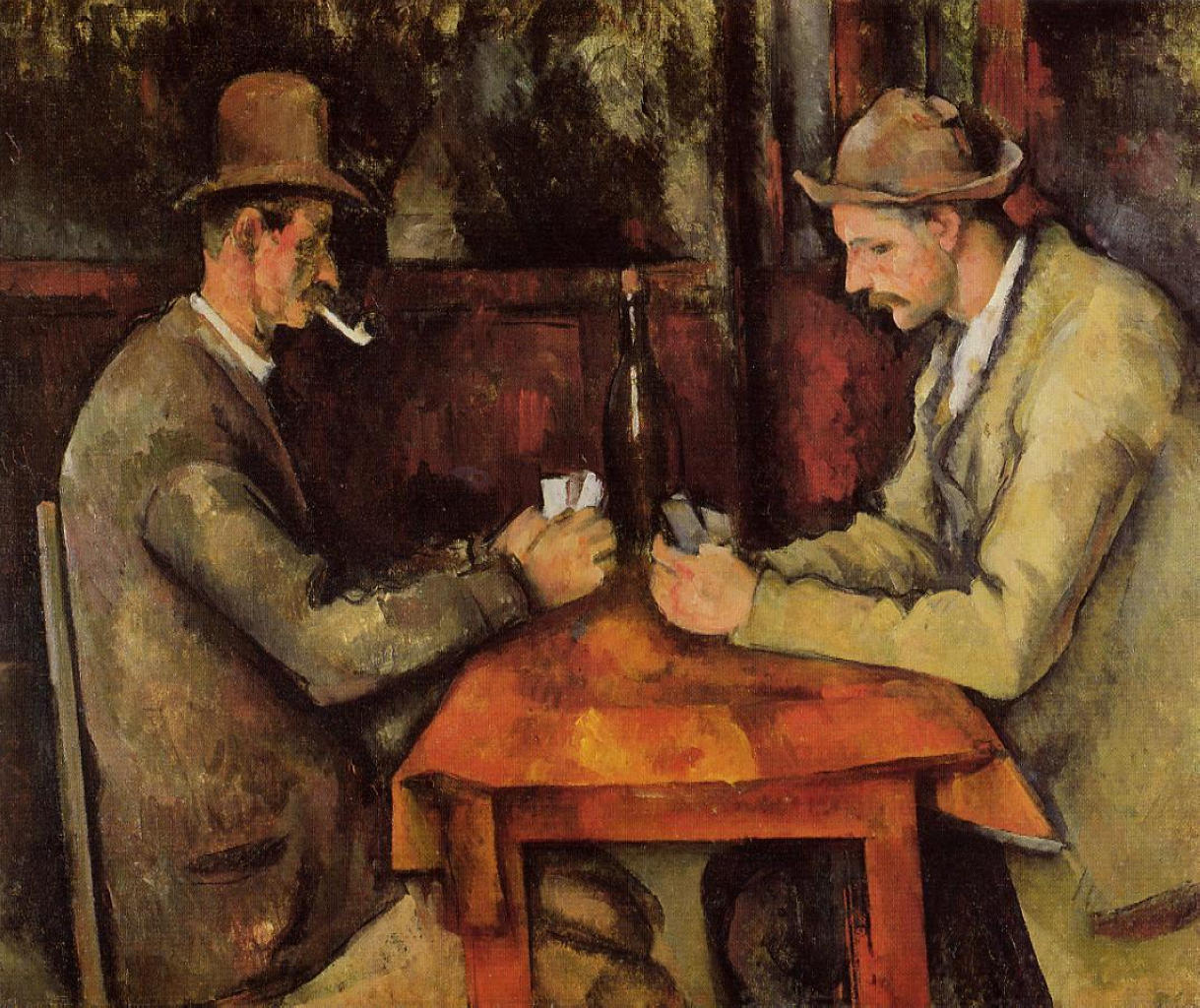

That van Gogh’s letters are so readable, that they are so rich, basically argues against him, just as it argues against a painter (holding up Cézanne for comparison) that he wanted or knew or experienced this and that; that blue called for orange and green for red: that, secretly listening in his eye’s interior, he had heard such things spoken, the inquisitive one.

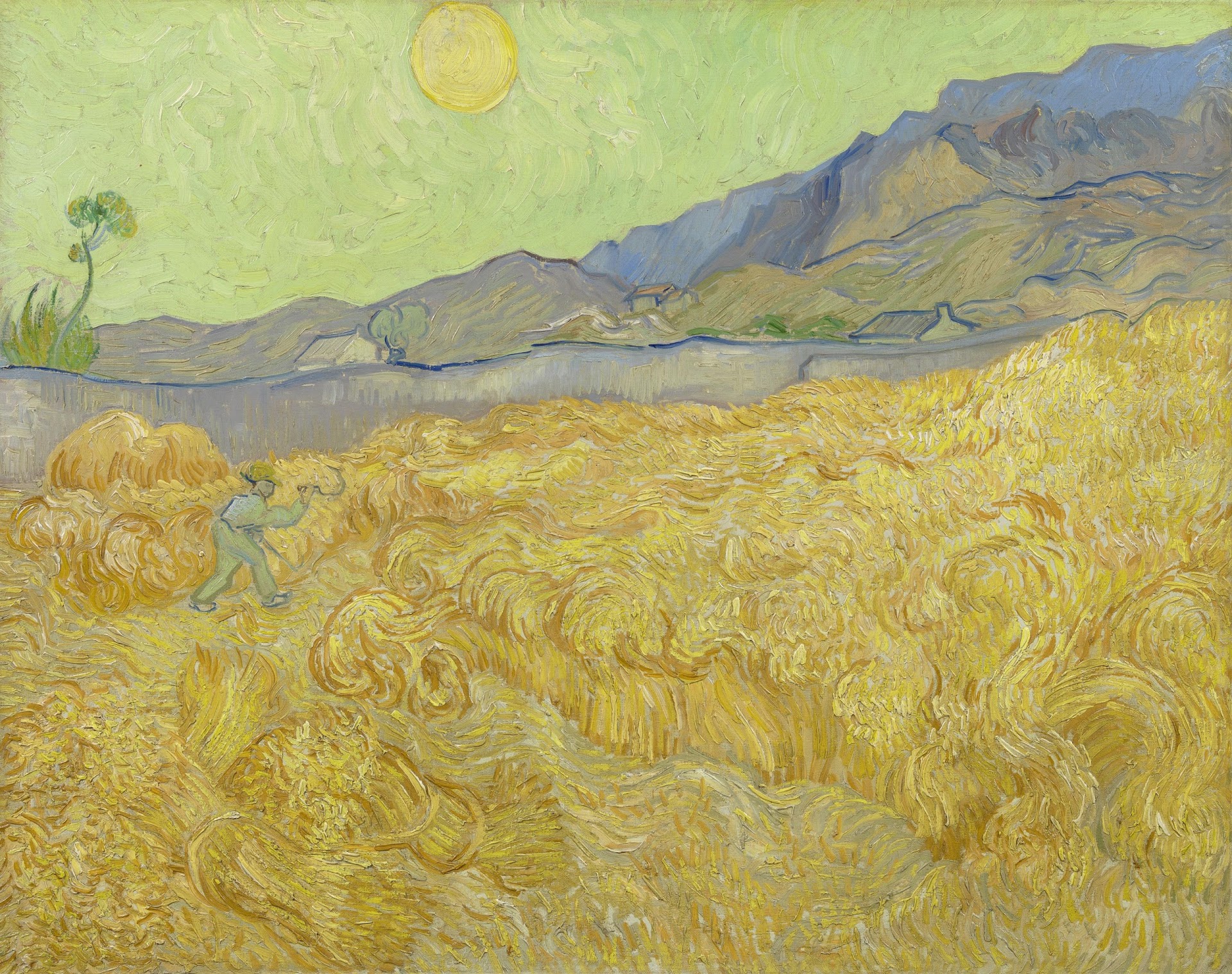

And so he painted pictures on the strength of a single contradiction, thinking, additionally, of the Japanese simplification of color, which sets a plane on the next higher or next lower tone, summed up under an aggregate value; leading, in turn, to the drawn and explicit (i.e., invented) contour of the Japanese as a frame for the coordinated planes; leading, in other words, to a great deal of intentionality and arbitrariness—in short, to decoration.

Cézanne, too, was provoked by the letters of a writing painter—who, accordingly, wasn’t really a painter—to express himself on matters of painting; but when you see the few letters the old man wrote: how awkward this effort at self-explication remains, and how extremely repugnant it was to him.

He was almost incapable of saying anything.

The sentences in which he made the attempt become long and convoluted, they balk and bristle, get knotted up, and finally he drops them, beside himself with rage.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

THE WORK

The idea that a painter shouldn’t be able to express their insights in words would rob many a great painter of the title. Cézanne, by the way, would be one of them (his letters to Bernard, the only ones Rilke read, represent only a fraction of his writing).

This is one of Rilke’s ideas I find really hard to swallow (I wrote more about it here.)

On a more personal note:

I know, of course I know, that my resistance to this idea is not about defending van Gogh at all (who absolutely doesn’t need my defense).

It is my own self I am defending, my own identity, being as I obviously am a “writing painter”, and so perhaps not really a painter.

But when all is said and done, each of us has to follow the path of one’s own unique expression, towards and beyond one’s “custom-made” risks and dangers. In the end, all of them have to be faced and transcended for something new and meaningful to emerge.

Thus Rilke shows me the trail of the law of my own growth, at the time when this help across time and space is most needed and welcome.

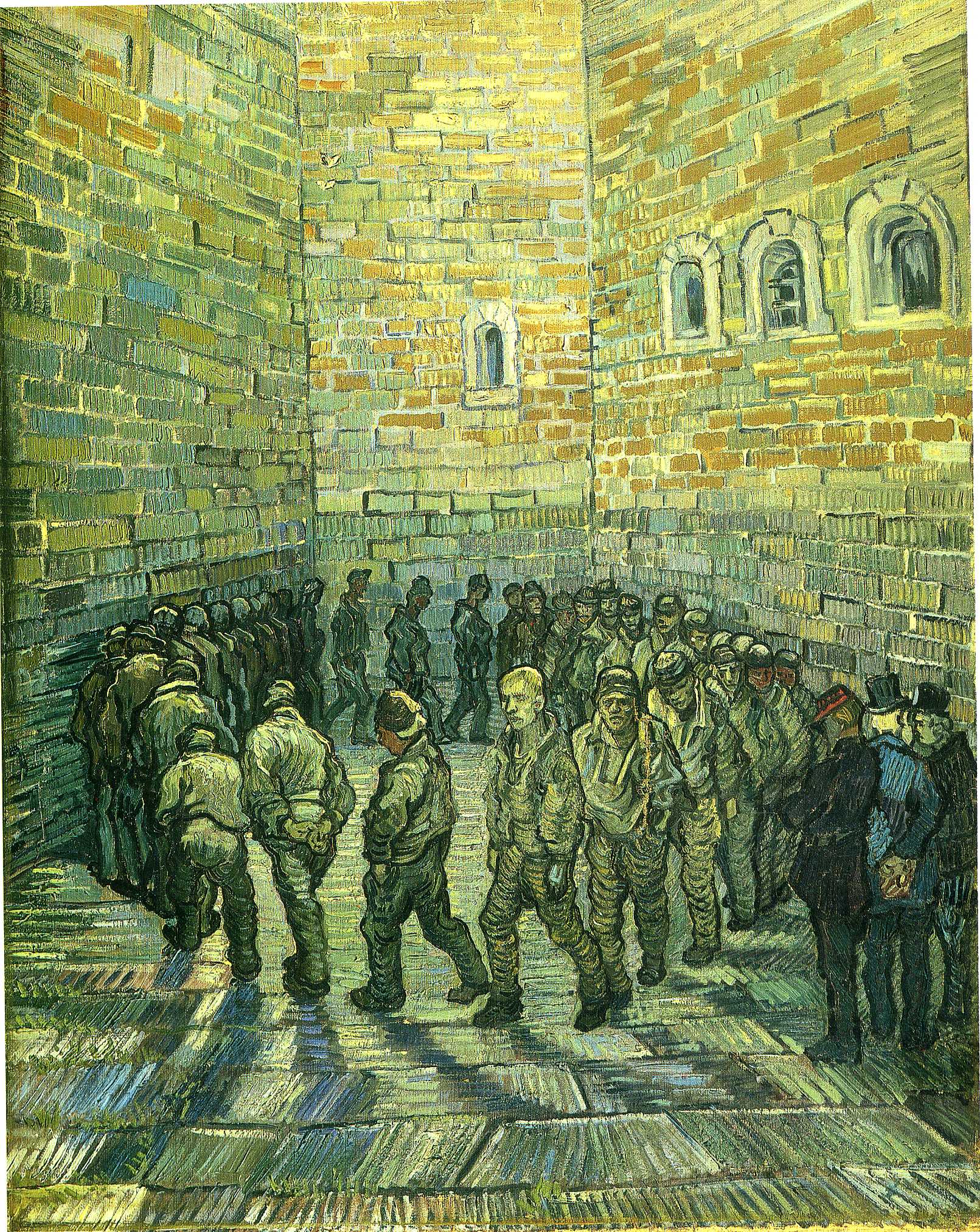

SEEING PRACTICE: VAN GOGH’s indescribable reality

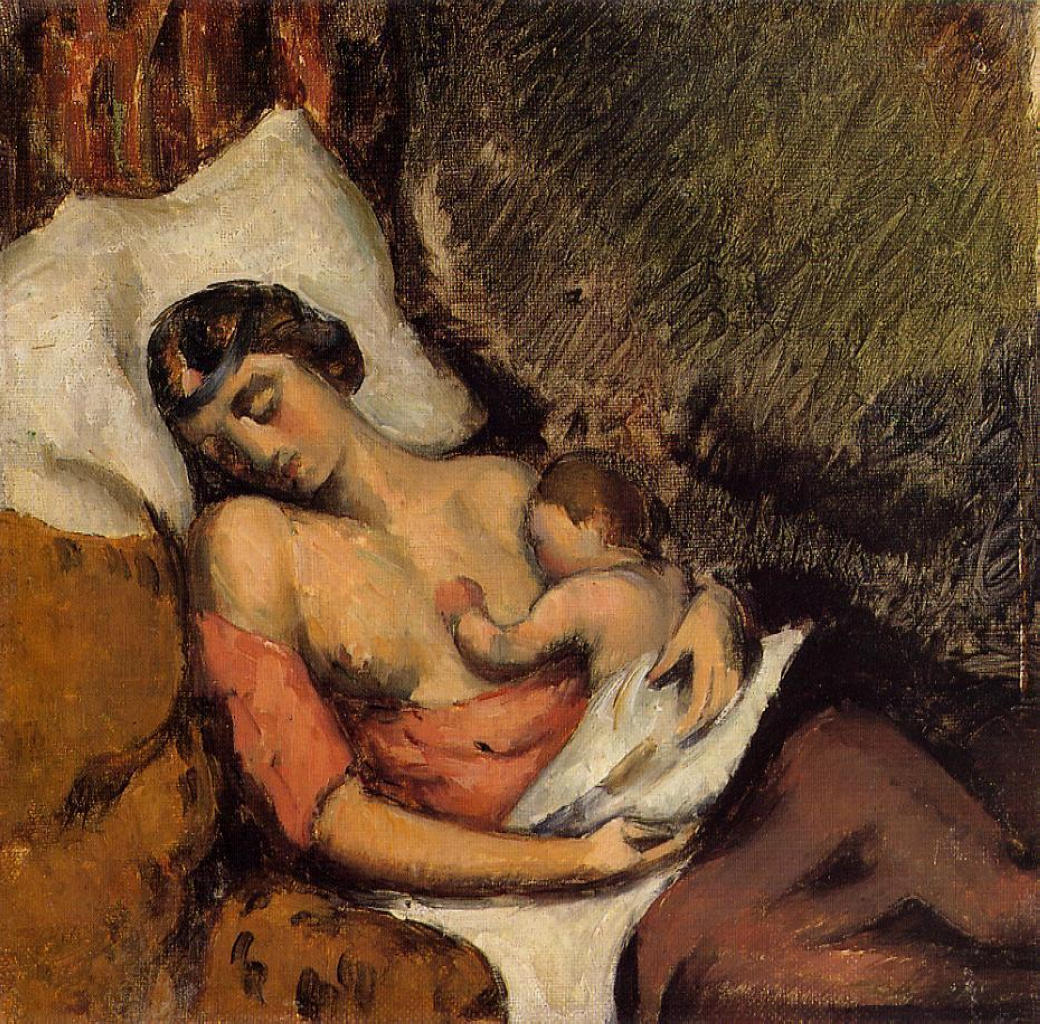

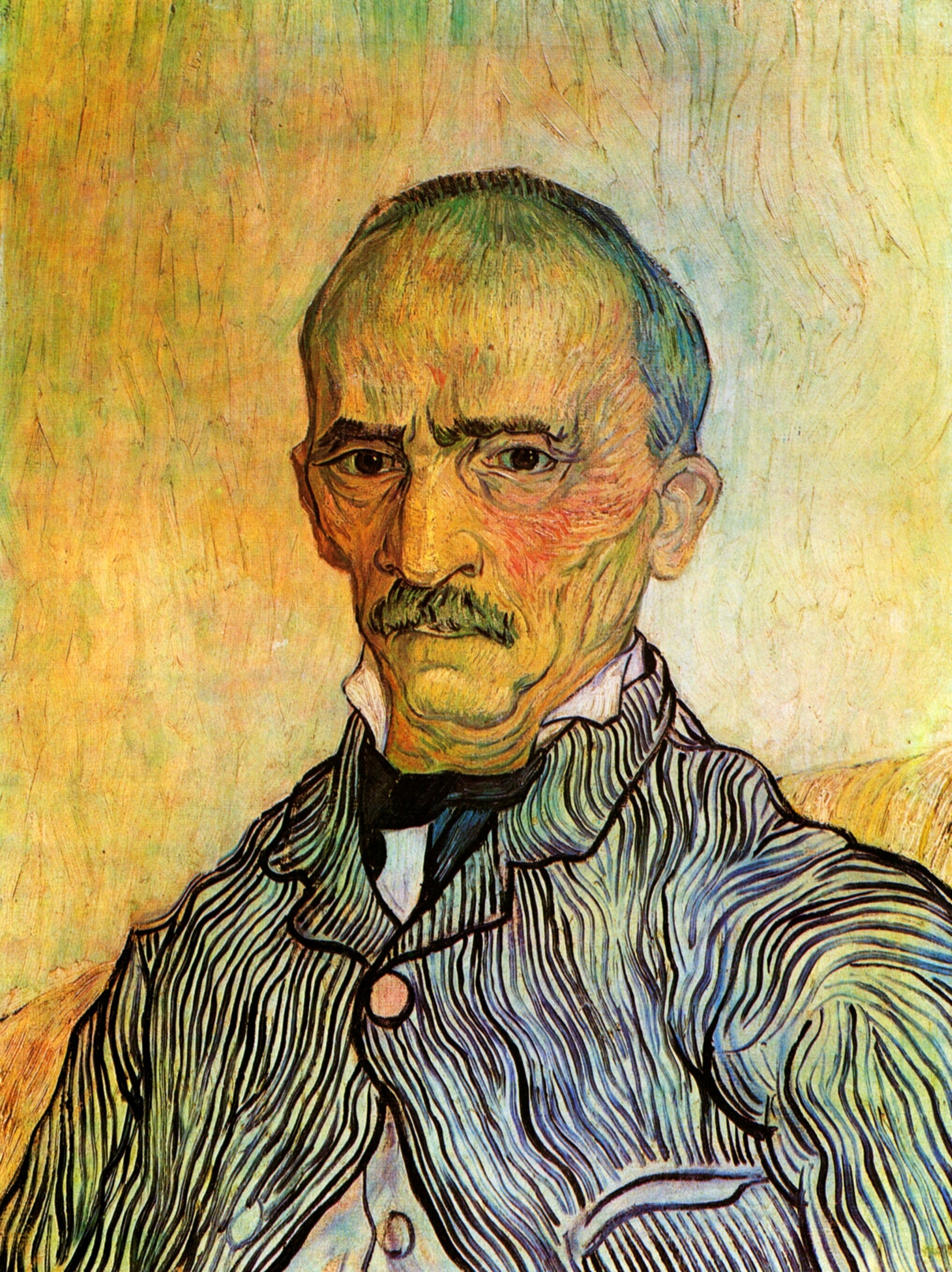

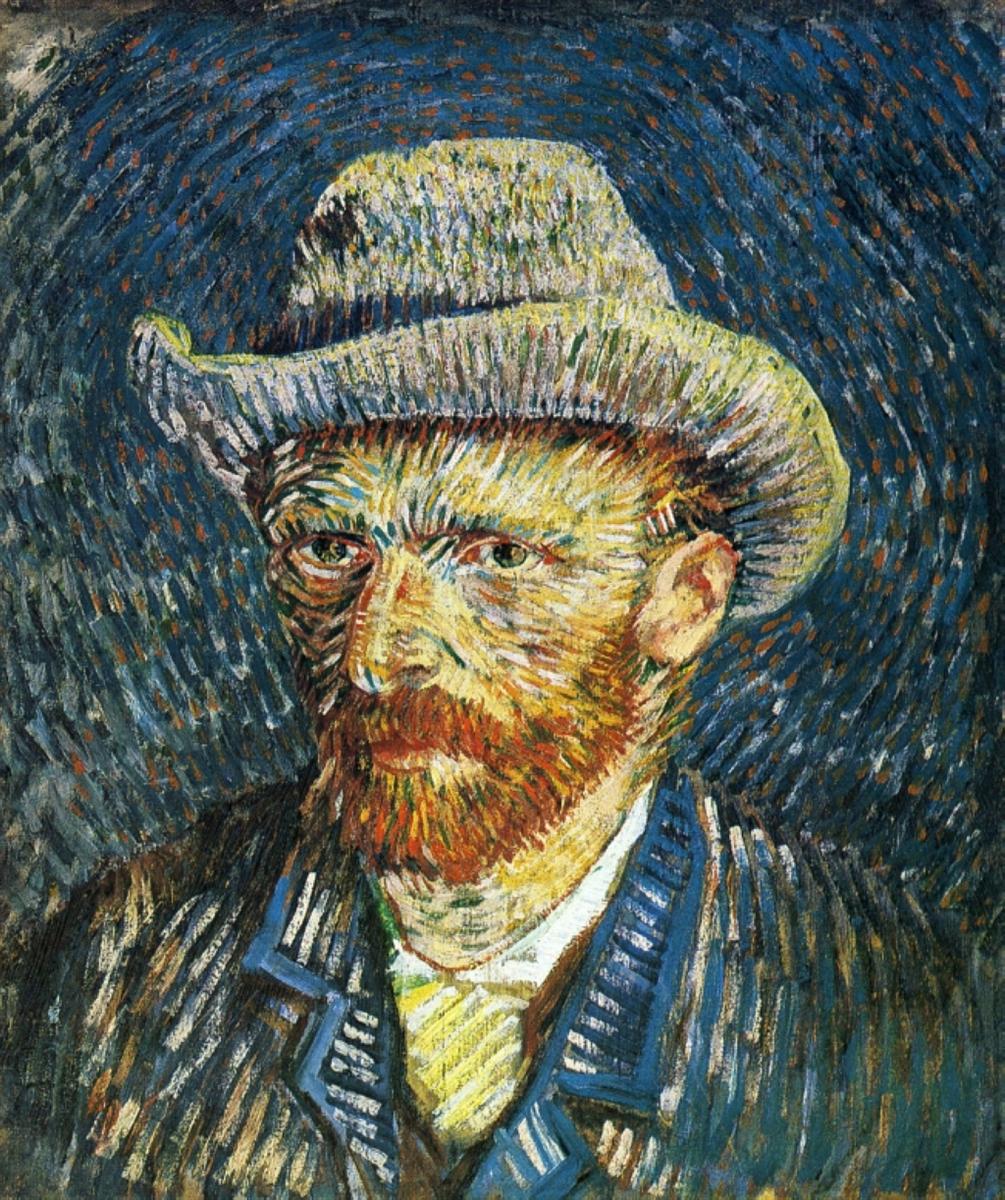

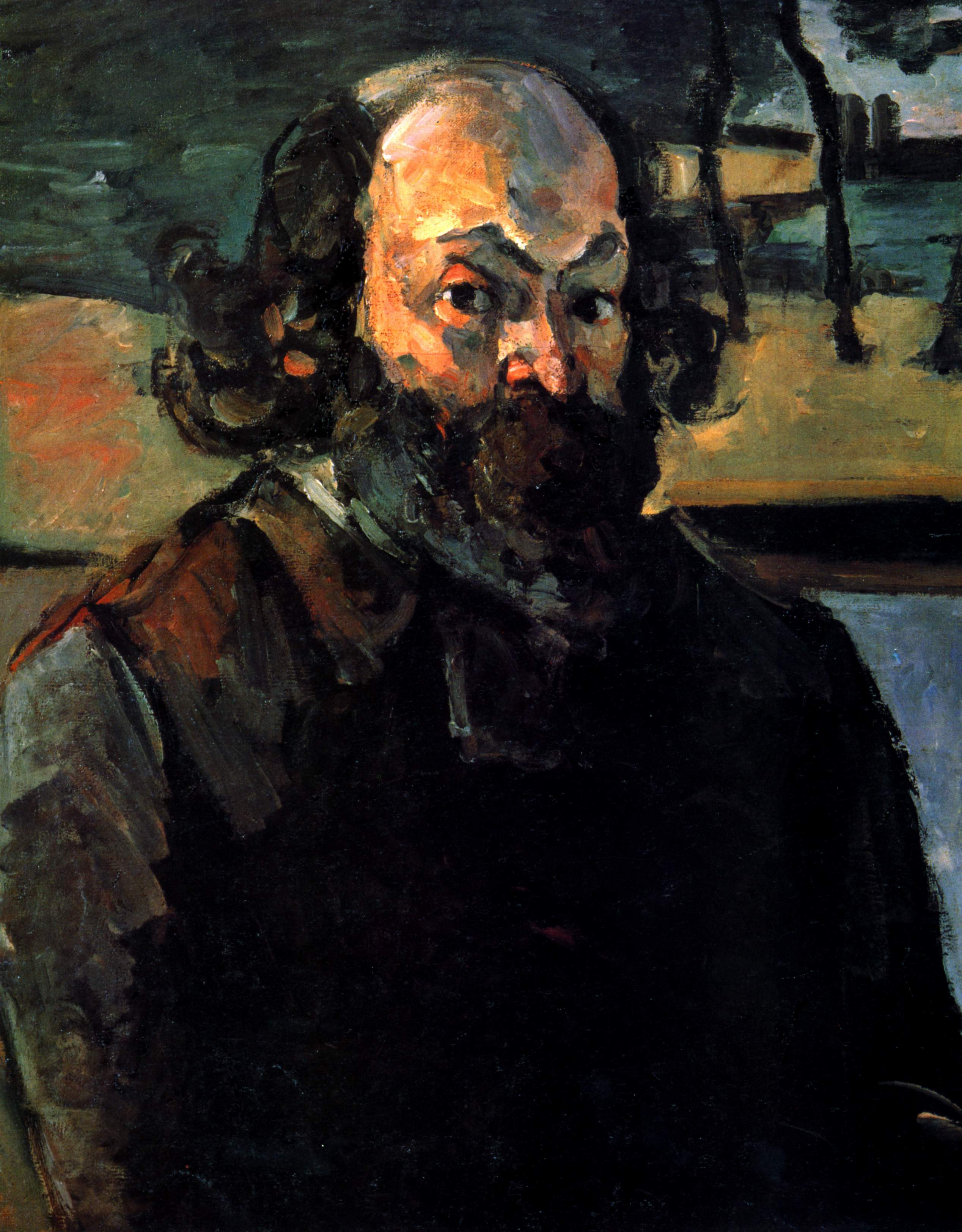

There are two self-portraits in this post, Cézanne’s and van Gogh’s, for you to compare.

This is one of van Gogh’s self-portraits that may lead the spectator to the idea of “intentionality and arbitrariness”, so unprecedented and unusual is the mutual intercourse of colors here.

But what if we take a leap of faith and see it AS IS, trusting van Gogh to show us HIS indescribable reality, not an arbitrary stylistic invention?