But this devotion to what is nearest, this is something I can’t do as yet, or only in my best moments, while it is at one’s worst moments that one really needs it.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

OCTOBER 4, 1907

… one is still so far away from being able to work at all times.

Van Gogh could perhaps lose his composure, but behind it there was always his work, he could no longer lose that. And Rodin, when he’s not feeling well, is very close to his work, writes beautiful things on countless pieces of paper, reads Plato and follows him in his thought.

But I have a feeling that this is not just the result of discipline or compulsion (otherwise it would be tiring, the way I’ve been tired from working in recent weeks); it is all joy; it is natural well-being in the one thing that surpasses everything else.

Perhaps one has to have a clearer insight into the nature of one’s “task,” get a more tangible hold on it, recognize it in a hundred details. I believe I do feel what van Gogh must have felt at a certain juncture, and it is a strong and great feeling: that everything is yet to be done: everything.

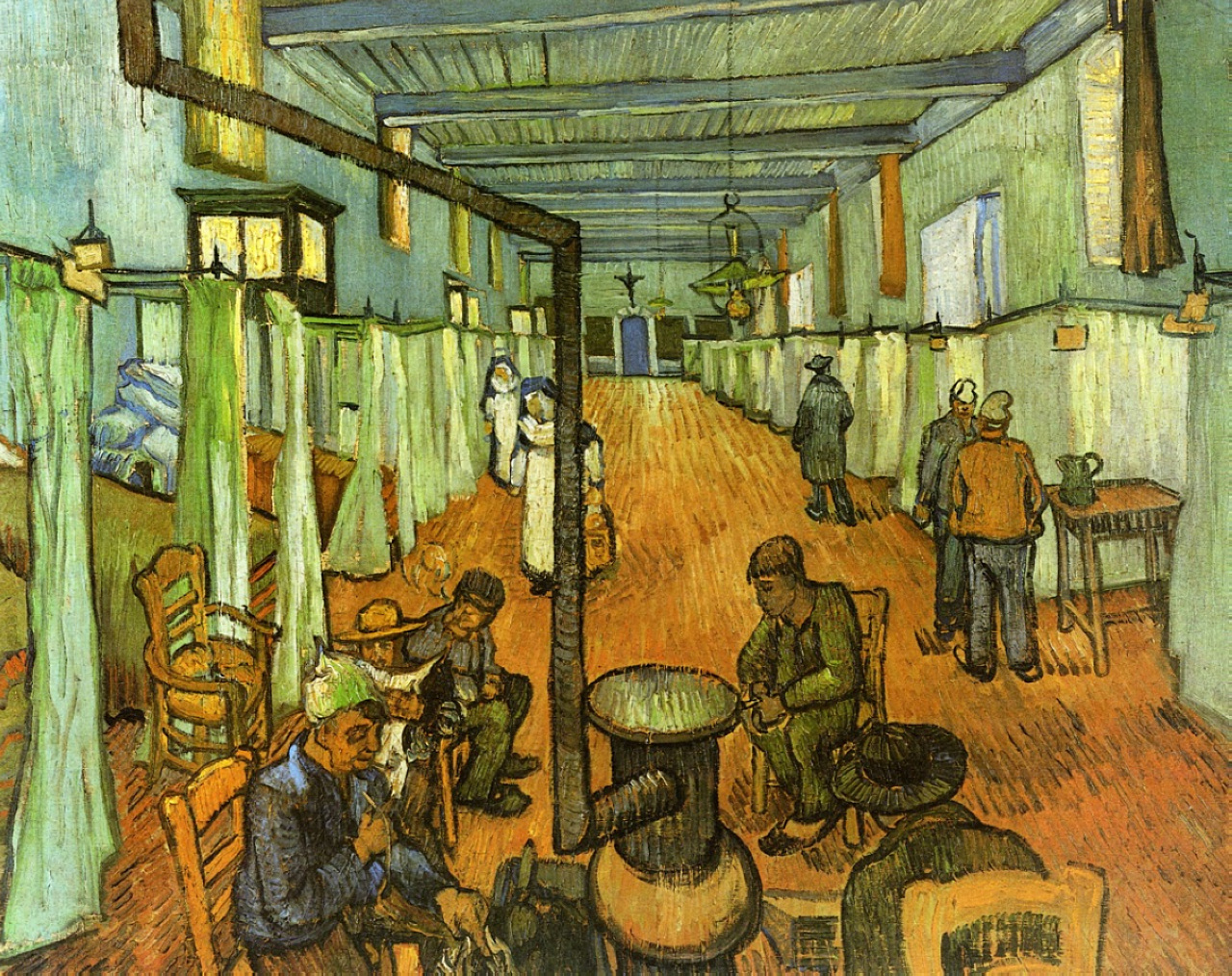

But this devotion to what is nearest, this is something I can’t do as yet, or only in my best moments, while it is at one’s worst moments that one really needs it. Van Gogh could paint an Intérieur d’hôpital, and on his most fearful days he painted the most fearful objects.

How else could he have survived.

This is what must be attained, and I have a definite sense that it can’t be forced. It must come out of insight, from pleasure, from no longer being able to postpone the work in view of all there is to be done.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

THE WORK

Is it possible to “work at all times”? Science tells us that it is not (but then, its findings change so dizzyingly rapidly nowadays…)

For Rilke, staying “within the work” all the time is unequivocally a prerequisite for any real achievement. This is the lesson he reads in the lives of Rodin, van Gogh, and then, later on, Cézanne… He looks at them, and finds himself lacking.

But in the course of these letters, one sees how his work unfolds when he as it were is not looking, effortlessly.

This book itself, undoubtedly one of his major achievements, is being written while he is trying to force himself to do something else (and even, at some later point, resolving that he must never write about Cézanne at all…).

SEEING PRACTICE: FEARFUL OBJECTS

Rilke writes: “… on his most fearful days he (van Gogh) painted the most fearful objects — how else could he have survived”. Here is another example, a drawing from the asylum van Gogh stayed in after his breakdown.

We now know it must have been one of the bad, most fearful days, because when van Gogh felt up to it, he ventured to paint outside. And he is drawing the most fearful things: the walls he imprisoned himself in, the door which only seems open, because he cannot cross the threshold.

Can we, too, look at our fears with this courage, with this kind of attention?