… airy blue, blue sea, red roofs, talking to each other in Green and very moved in this inner conversation, and full of mutual understanding …

Rainer Maria Rilke

This is the second part of Rilke’s letter from Prague.

NOVEMBER 7, 1907 (Part 2)

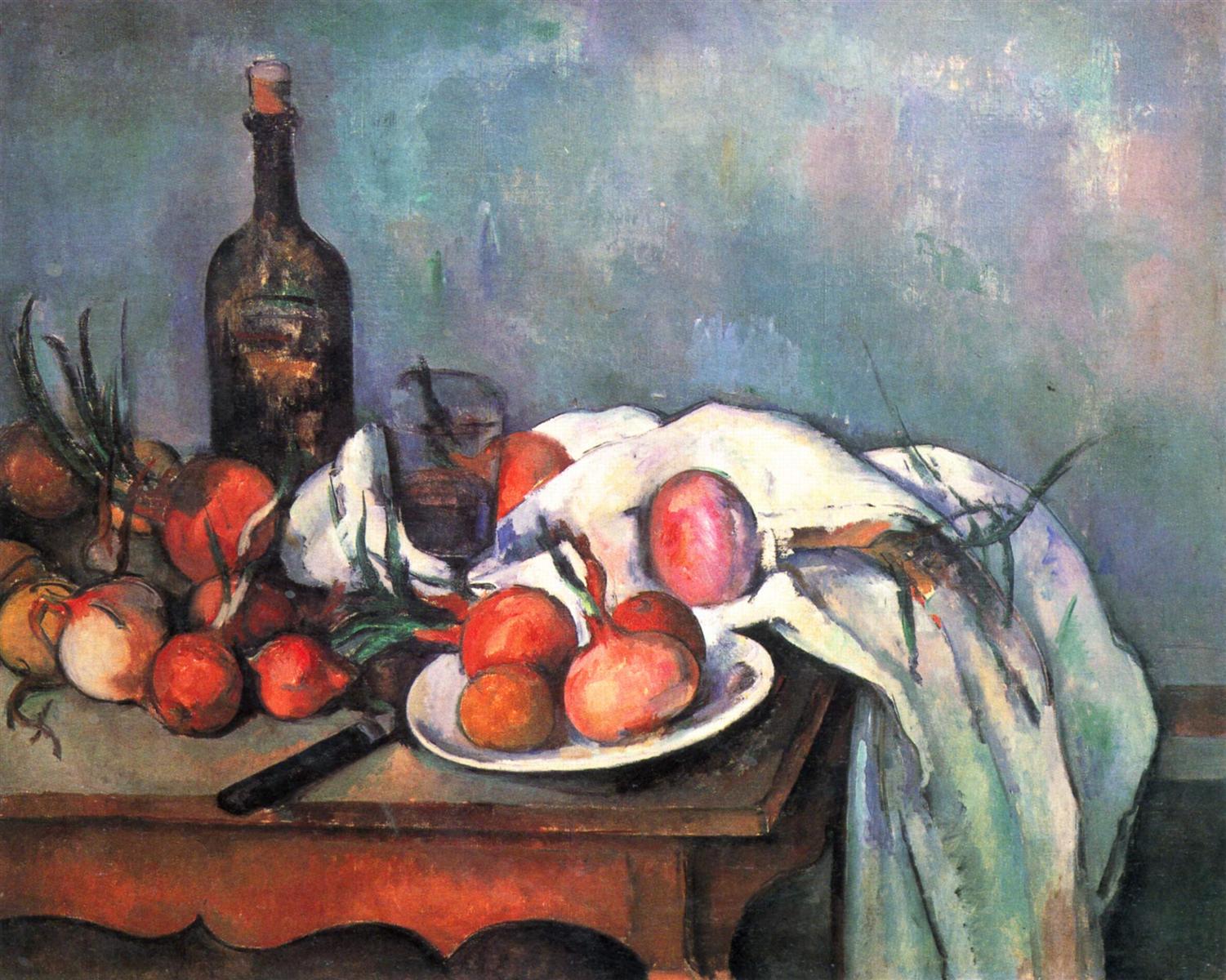

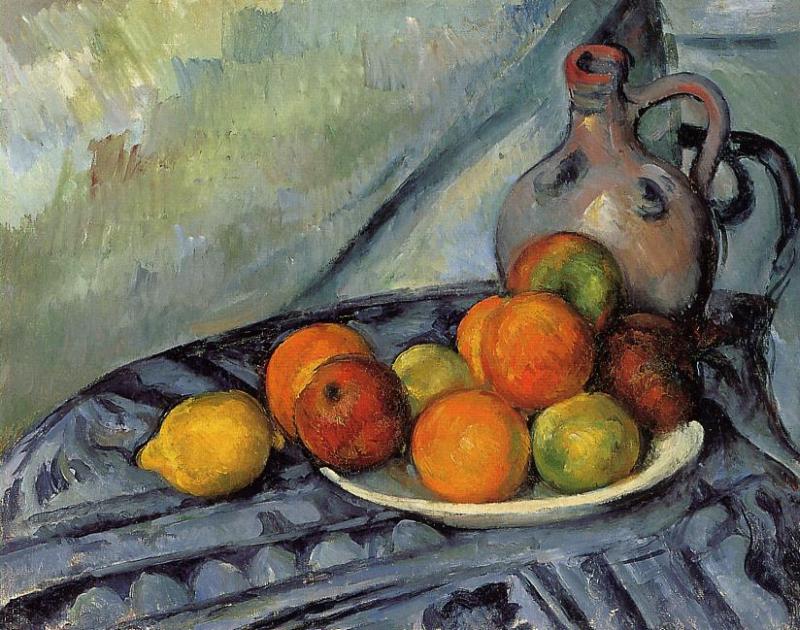

Next to this, a nature morte with a blue cover; between its bourgeois cotton blue and the wall, which is overlaid with a light cloudy bluishness, an exquisite, large, gray-glazed ginger pot holding its own between right and left.

An earthy-green bottle of yellow Curaçao and furthermore a clay vase with a green glaze reaching down two thirds of it from the top. On the other side, in the blue cover, some apples have partly rolled out from a porcelain bowl whose white is determined by the cover’s blue.

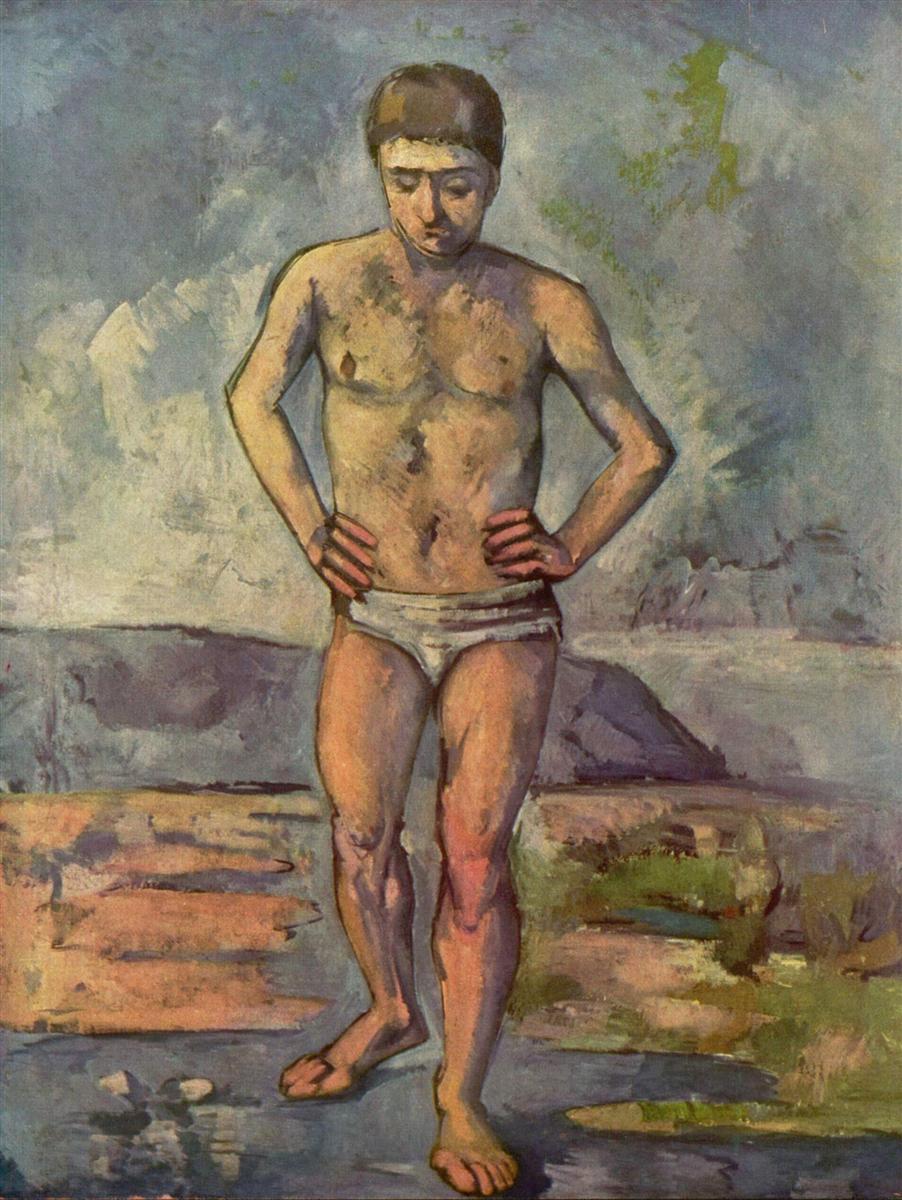

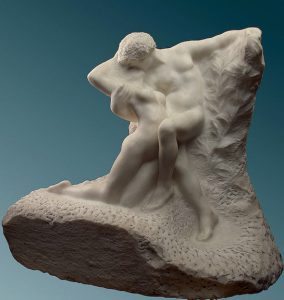

This rolling of red into blue is an action that seems to arise as naturally from the colorful events in the picture as the relationship between two Rodin nudes does from their sculptural affinity.

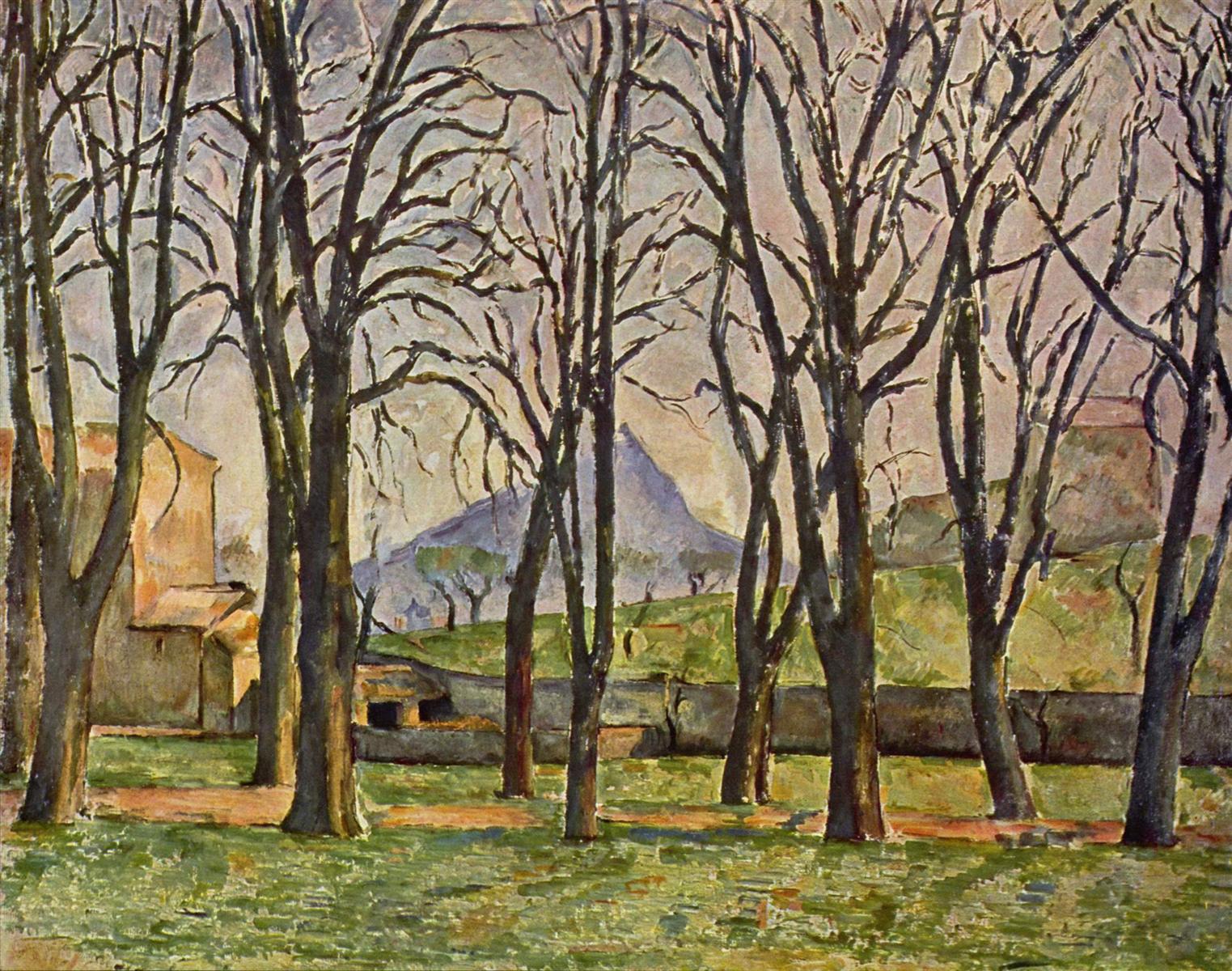

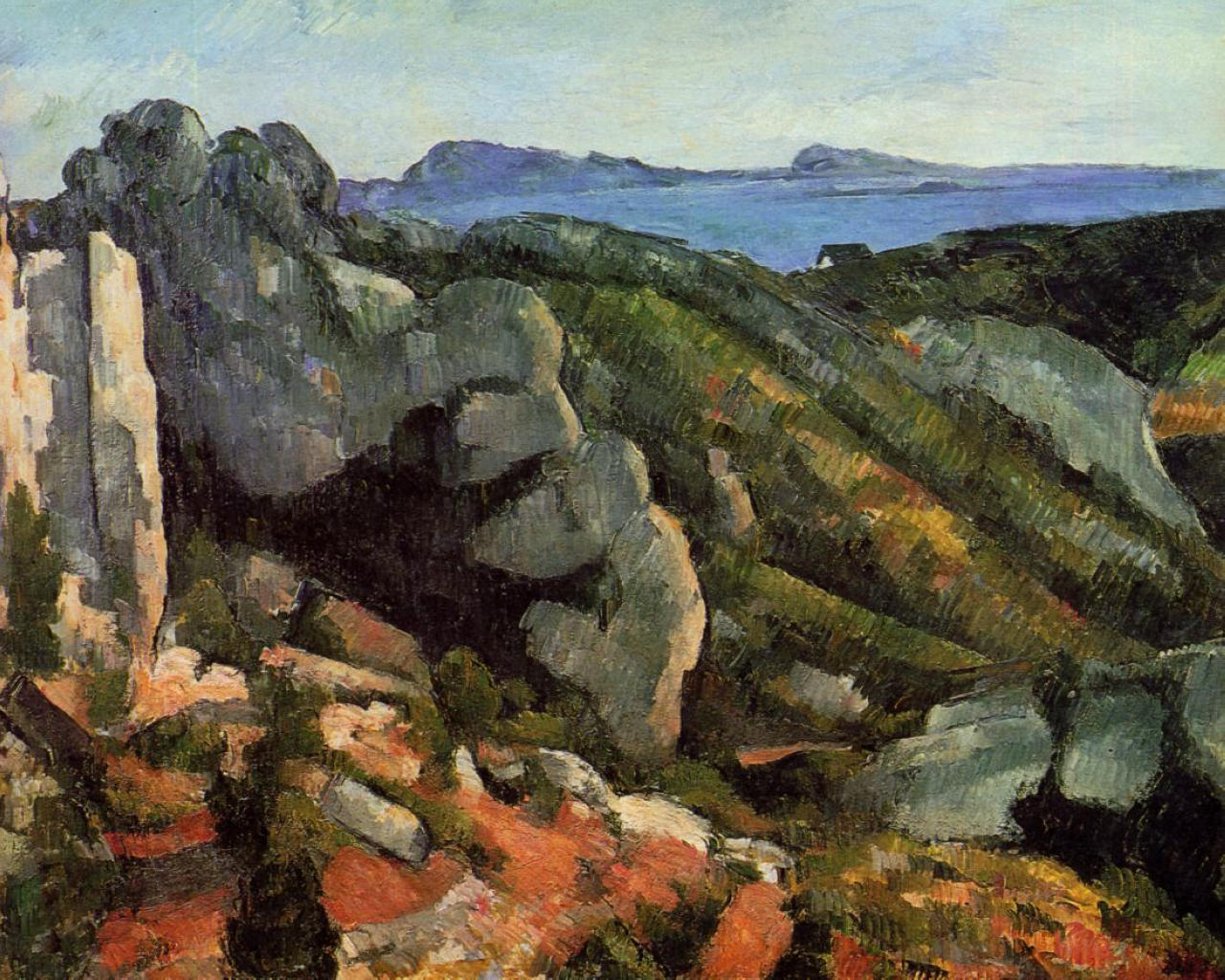

And finally a landscape of airy blue, blue sea, red roofs, talking to each other in Green and very moved in this inner conversation, and full of mutual understanding …

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

The metaphor of painting as a conversation among colors unfolds, and now one color (Green) becomes the language the others are using to communicate.

And with this, the letters end, and we are left on our own.