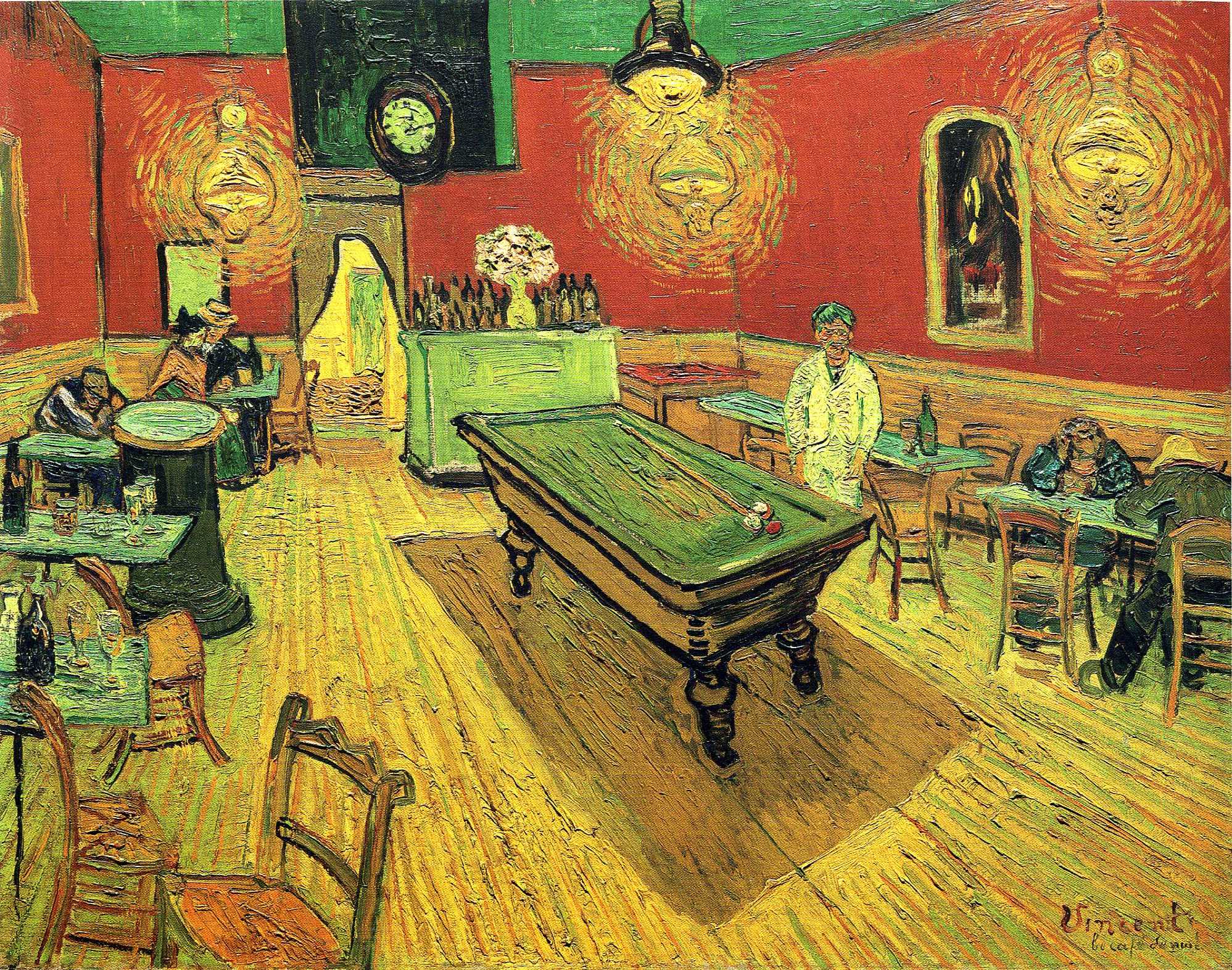

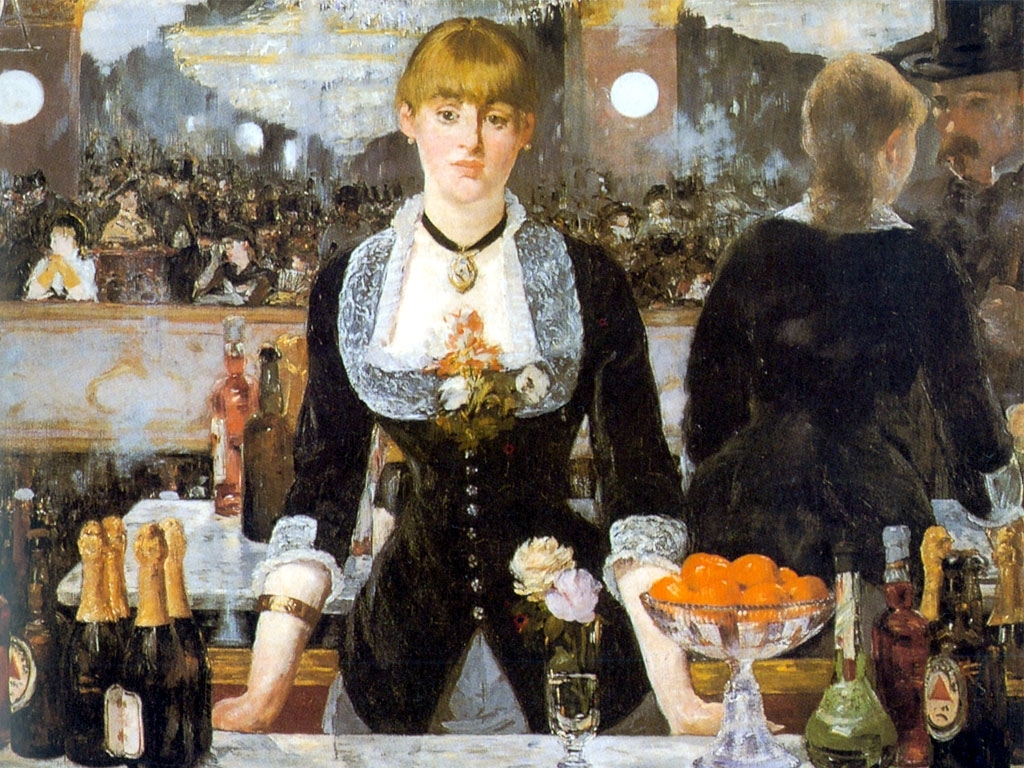

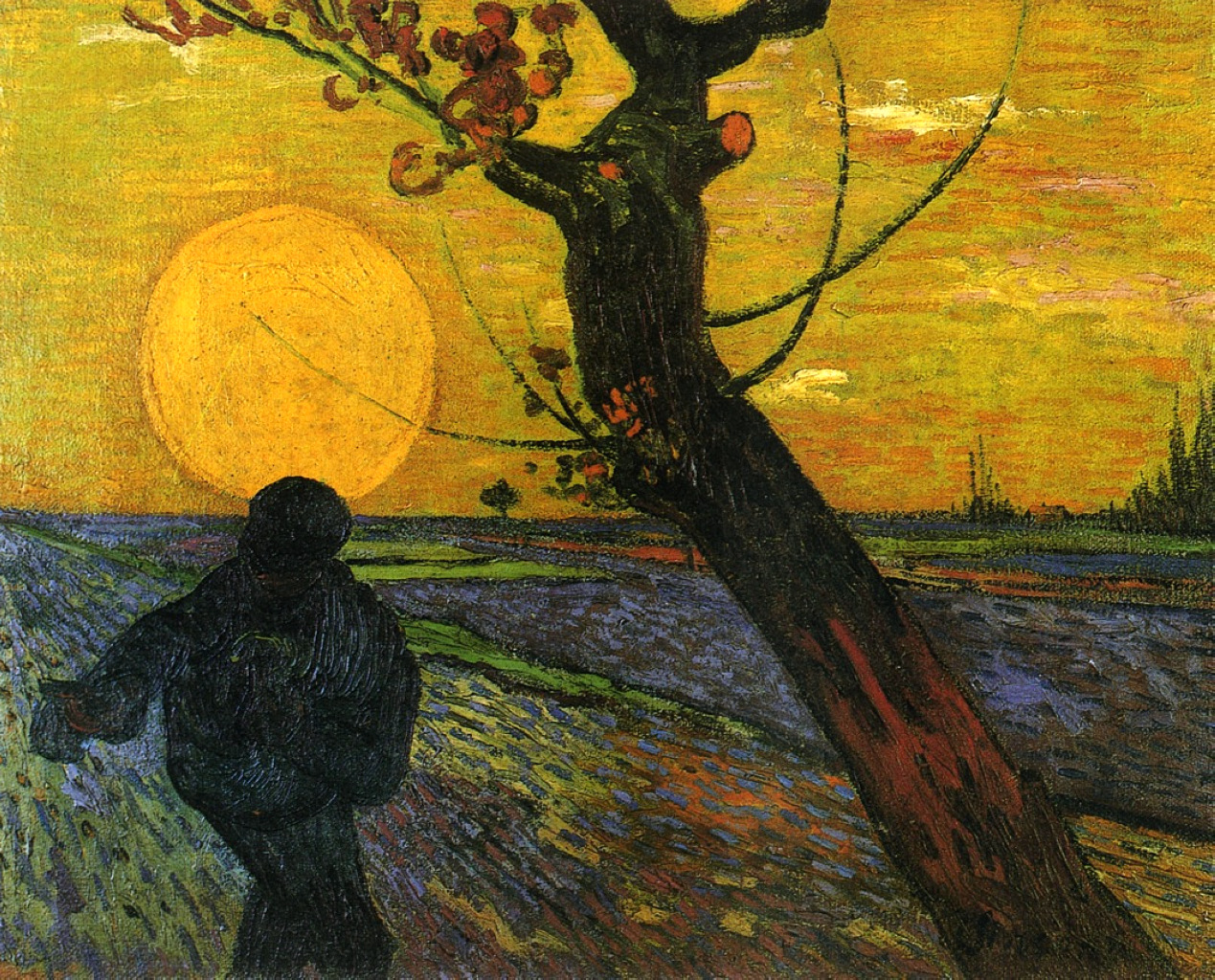

Another painting by van Gogh, but how different are its greens… one can hardly believe that we can use one word to name these colors.

OCTOBER 17, 1907 (Part 3)

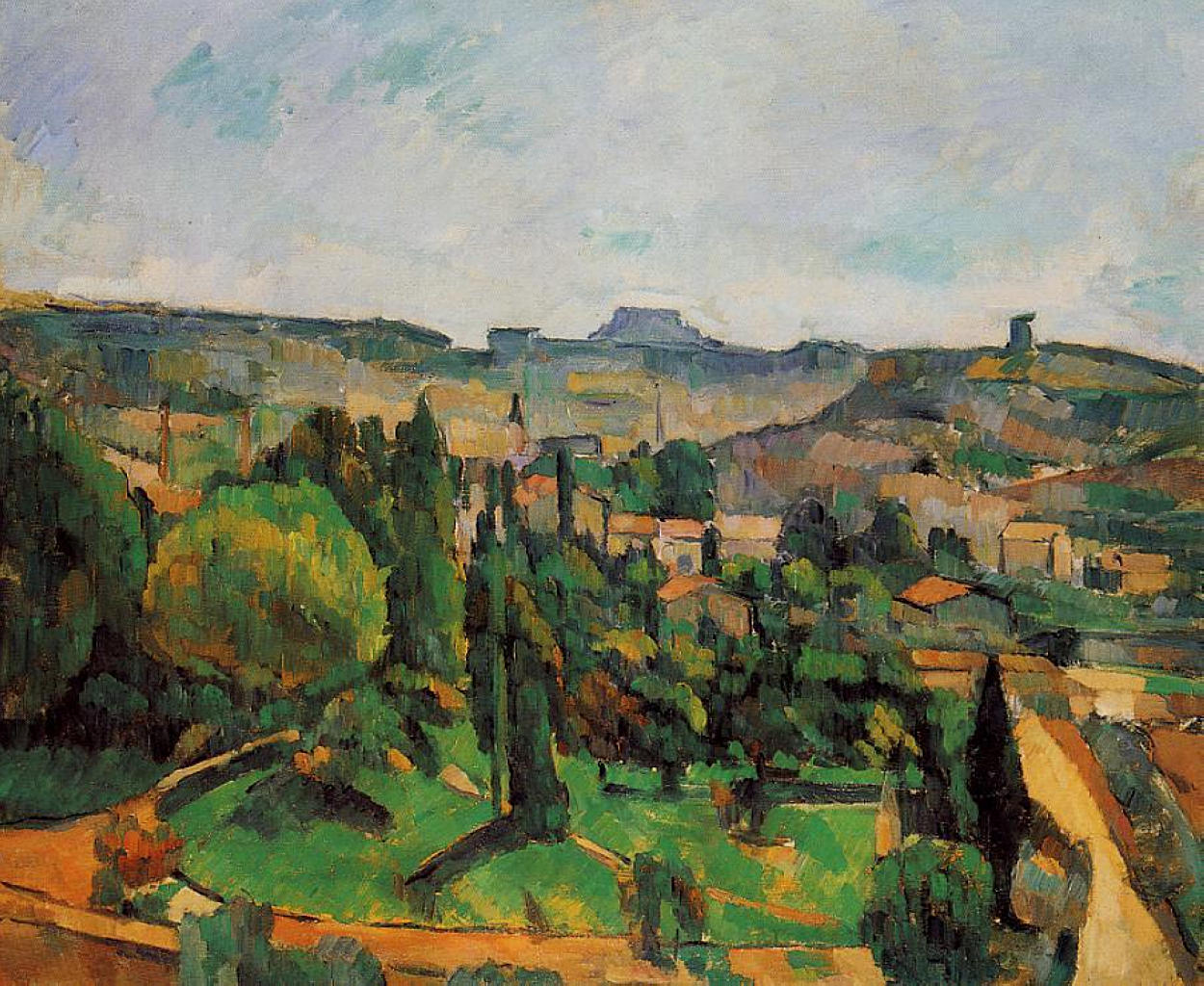

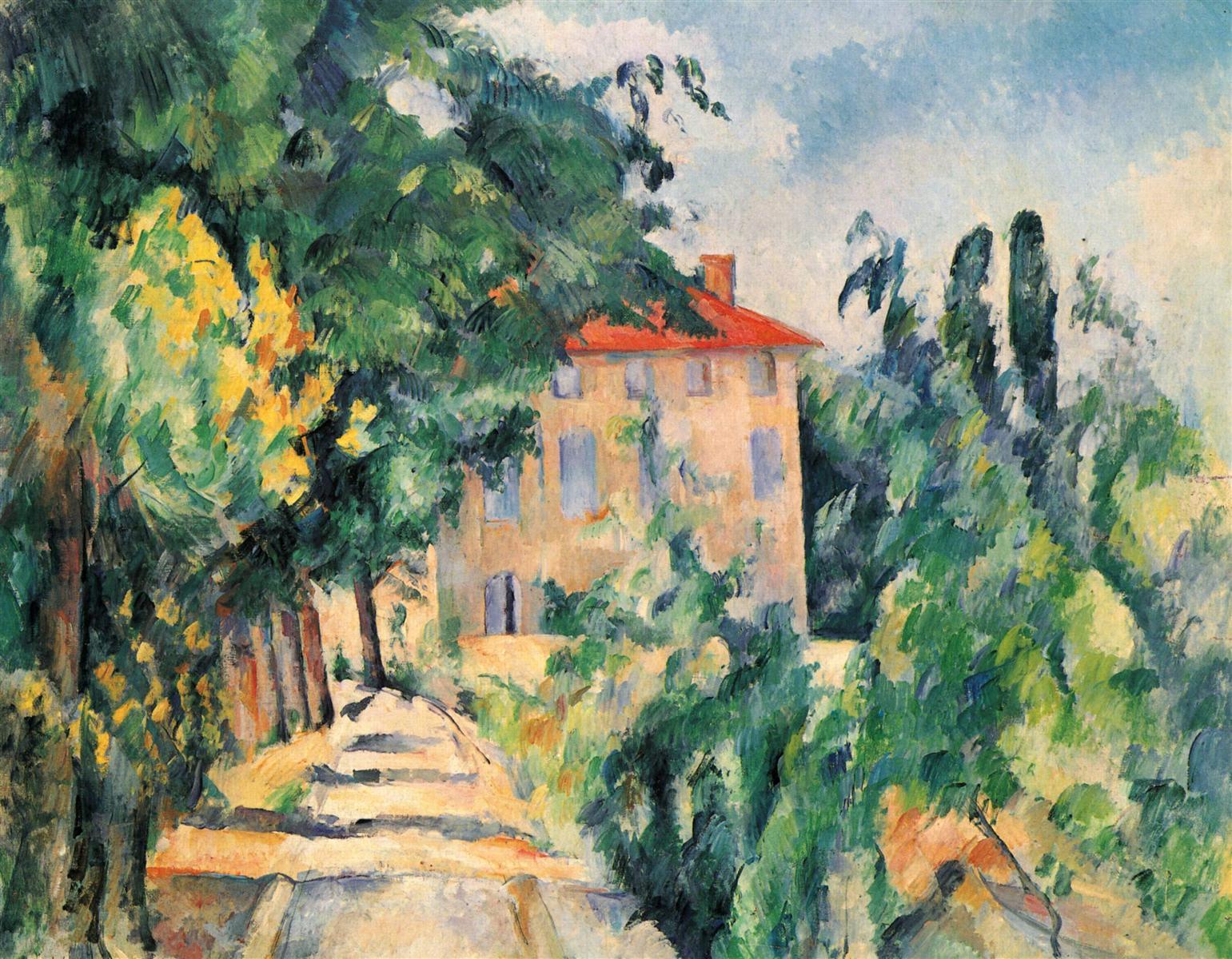

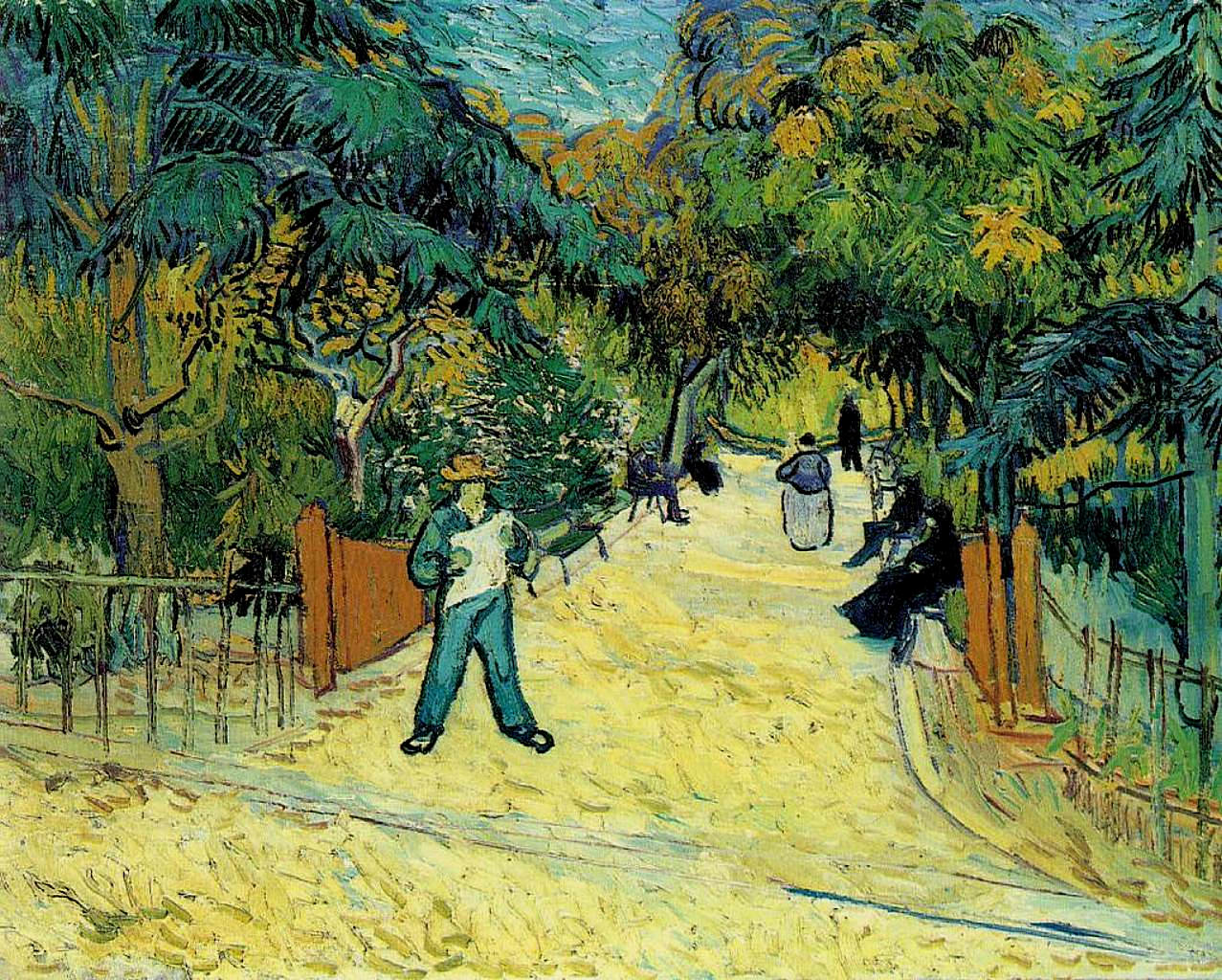

A park or an alley in a town park in Arles, with black people on benches on the right and left, a blue newspaper reader in front and a violet woman in the back, beneath and among blows and slashes of tree- and bush-green.

Rainer Maria Rilke to Clara Rilke

STORYLINE: COLORS AND WORDS

Yesterday, we looked at a green that was deep and utterly shallow in artificial wakefulness. Today, it is tree- and bush-green in full sunlight.

SEEING PRACTICE: COLOR GREEN

Compare the greens of the park with the greens of the night cafe. What is it that makes them so radically different?